Today marks the third anniversary of the GARP Climate Risk Podcast. We have learnt a huge amount from talking to a wide range of guests. This article explores the rich insights it has provided on how climate change is impacting the world of business and finance, setting out 5 key areas where there have been important lessons for risk professionals.

Financial firms are under increasing pressure to demonstrate sound management of the risks from climate change. But the impacts are likely to be far-reaching and not always immediately obvious. That's why we adopted a multi-disciplinary approach in the podcast, hearing from a range of perspectives such as climate scientists, economists, risk professionals, supervisors, and board members. This article highlights five key areas that have been explored in the podcast, with links to episodes throughout:

- Why should we be so worried about limiting global warming? And how risky is it?

- Reaching net zero is critical – the question is how and when?

- How transition risks will affect portfolios as we transition to net zero

- The different ways physical and transition risks will impact portfolios, with significant commercial opportunities opening up

- The enormous opportunities for risk professionals to help their firms navigate the risks

- Why should we be so worried about limiting global warming? And how risky is it?

Global warming is giving rise to a whole range of ‘physical risks’, such as more frequent and intense heat extremes, droughts in some regions, heavy precipitation, and reductions in Arctic sea ice, snow cover and permafrost. But using an average temperature increase – such as 1.5oC – to describe the risks is inadequate. The whole distribution of climate outcomes is changing, meaning a significant increase in the probability of tail risks. Sudden changes in conditions may also occur as various 'tipping points’ are crossed, where a small change in warming can trigger feedback loops that lead to a cascade of other irreversible impacts.

From a risk management perspective, these outcomes can lead to devastating impacts. For example, climate change creates cascading risks such as crop failures, leading to food shortages and at times civil unrest (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Summary of the major systemic risk dynamics

Source: Climate change risk assessment, September 2021, Daniel Quiggin, Kris De Meyer, Lucy Hubble-Rose and Antony Froggatt (Chatham House)

Archaeologists have shed light on how impactful natural changes in the climate have been on populations in the past, in some instances wiping out civilisations. Local adaptation has tended to be the most effective response, but it has its limits, particularly when faced with more extreme impacts, such as centuries-long megadroughts. At some point, people are forced to move as their lands become uninhabitable. A key risk of man-made or ‘anthropogenic’ climate change today is that it will give rise to significant migration, putting pressure on governments and populations of receiving countries. One guest argued that this is already happening today.

Up to now, the oceans have buffered us against the worst impacts of climate change, absorbing about a third of all of our carbon emissions, and around 90% of the temperature increase from global warming. This has shielded us from even worse physical impacts, but at a devasting cost to marine biodiversity. We need to be very careful as the oceans’ ability to act as a carbon sink will become less effective over time.

Many guests have reminded us about other environmental risks, which are often directly related to climate change, such as biodiversity loss. We heard, for example, how hand pollination is now needed as there are no longer sufficient populations of pollinating insects in some Asian countries. Although policy attention on biodiversity loss has lagged climate change, it is getting far more attention now, in part due to new reporting frameworks such as the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures, and to the recent UN Biodiversity Conference (COP15 in December 2022). Risk professionals need to be aware of this shifting focus as it will influence the risks associated with doing certain types of business (e.g., with counterparties that are exposed to biodiversity risks). For more details, please see our recently published introductory guide.

- Reaching net zero is critical – the question is how and when?

Climate science has established a near-linear relationship between cumulative net emissions and temperature increases. Accordingly, stabilizing the global temperature at any level implies that ‘net’ emissions need to be reduced to zero. ‘Net’ refers to the balance between emissions produced (e.g., by industrial production) and those removed from the atmosphere (e.g., by reforestation or direct air capture). A key question in many of the podcasts has been how and when can we reach net zero?

The focus on limiting global warming to 1.5oC has been translated into reaching net zero by 2050. But the simplicity of the target hides many complex questions, such as the timing and trajectory of emissions, the scope of emissions covered and how ‘net’ is defined. For example, if a nation’s net-zero target only considered emissions from its domestic production, then offshoring could cut its emissions without necessarily doing anything to reduce overall global emissions. Likewise, at the level of a firm, a bank that stops lending to a high-polluting manufacturer may be cleaning up its own balance sheet, but may not be reducing real world emissions as another financial institution (possibly less scrupulous) could step in and provide new lending.

Another critical point is that reducing emissions to zero in the year 2049 will not help us keep warming to under 1.5oC, as it is the cumulative amount of emissions that matters. In other words, the path we follow matters hugely. We need to cut emissions by 45% by 2030, and they need to continue reducing until they reach net zero by 2050 to have a hope of reaching that target.

We have spoken quite a bit on the podcast about the importance of the annual so-called Conference of the Parties (COPs). These are meetings of the countries that joined the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC), coming together to make commitments to reduce emissions and discuss ways of tackling the rising risks. Yet, the commitments so far – the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDCs) – from the two most recent COPs have been insufficient, leaving the world with a significant implementation gap, as Figure 2 indicates.

Figure 2: Implementation Gap to Limit Warming to 1.5 degrees

Source: Carbon Action Tracker

The COPs have brought mixed reactions from our guests, with some hopeful that significant progress will be made, but others extremely critical. Some regard the 1.5oC target as highly unrealistic, in part because of the politics of the changes required. But also, the COPs rely on reaching unanimous support across all participating nations, which tends to drive it to the lowest common denominator. One guest suggested that the COPs lag rather than lead climate action.

For risk professionals, understanding the way that policy is evolving is critical to being able to assess the likelihood of different possible future scenarios and their potential impacts on economic activity. For example, the longer that decisive action is postponed, the higher the probability of a later, more disorderly and more costly transition to net zero.

- How transition risks will affect portfolios as we transition to net zero

We have looked at several of the main drivers of transition risk – which are the risks that will arise as we transition to a lower-carbon economy. There are four main types:

(1) Policy and legal risks;

(3) Market risks (i.e. arising from changes in the supply and demand for goods and services); and

(4) Reputational risks (linked to changing consumer and investor sentiment).

The podcast has focused particular attention on policy changes, which are a critical element of the transition. From a risk management perspective, policy changes are uncertain, in terms of type of policy, speed of introduction and their future trajectory. Many economists favour a carbon tax to address the fundamental problem of emissions being associated with negative ‘free-riding’ externalities. Failure to introduce a comprehensive global carbon tax has meant that incentives are misaligned and the risks aren’t being priced properly.

We heard that it is politically easier to impose such a tax when it’s somewhat hidden, rather than obvious to consumers (e.g., adding to the price of a litre of fuel). But it is very likely that other policies will be needed, to overcome various market failures (such as private markets underinvesting in innovation or networks, such as EV charging infrastructure).

Politically, ‘cap and trade’ systems have been easier to implement than comprehensive carbon taxes and so are more prevalent. But regulatory and industrial policies often are the most effective ways to reduce emissions.

Risk professionals need to understand these challenges – as well as the other drivers of transition risk – when assessing risks to portfolios, as well as bearing in mind that policies will most likely be enacted differently across jurisdictions.

- The different ways physical and transition risks will impact portfolios, with significant commercial opportunities opening up

Transition risks will tend to hit sectors in differing ways, with high-emitting sectors being the obvious candidates for policies to stop their polluting. In contrast, the impacts of physical risk will be differentiated by location. Analyses of physical and transition risks will require new data sources, new methodologies and new business processes so that they become incorporated within day-to-day risk management.

Firms in the real economy (that is, non-financial firms) that are dealing with the risks from climate change will need to look beyond their own operations to those of their supply chain. This will take time as many are extremely complicated; indeed, we heard that supply chain decarbonization can take at least 10 years. Because the physical impacts from climate change are expected to intensify over time, firms with long-lived assets will be more affected than those with shorter-time frames, meaning that they should be scrutinised even more by risk professionals.

Some sectors will need more closely integrated planning, such as the energy and water systems, which have a growing reliance on each other. Even relatively low-carbon sectors will be affected; the film and television industry, for example, is considering both its own carbon emissions, as well as the influence that they have on public opinion. But we heard about potential ‘win wins’ which offer great investment opportunities, such as sustainable farming practices which both reduce emissions and build resilience. And there was a valuable reminder that adaptation will be needed alongside mitigation, as it is inevitable that further global warming will take place given lags in the climate system.

In the financial sector, different types of firms will be affected differently. Insurance has a potentially important role in risk reduction, through the provision of insurance products as well as giving incentives for better risk management. But as climate change worsens, some of the risks may become uninsurable. Asset owners also have a longer time horizon than many other financial firms, meaning that they will be more affected by a world of rising risks than companies with a short-term focus. Many asset owners have been actively engaging with real economy firms (and their asset managers) to address climate and environmental risks.

The good news is that half of the technology we need to reach net zero is currently available and the rest is being invested in, so there are plenty of investment opportunities. There are also opportunities to innovate by developing new financial products that help clients to cope with climate change. Some of these products have even become mainstream over recent years, such as green bonds. Underpinned by green ‘taxonomies’, which define the characteristics needed to call something ‘green’, the emergence of new products raises questions about the sustainability of many of today’s traditional financial products. For example, in one podcast it was argued that we might well see changes in products such as general purpose lending in the case of banks. This is a key area for risk professionals to understand: e.g., how are the products being marketed? Are they being properly priced and capitalized?

- The enormous opportunities for risk professionals to help their firms navigate the risks

Embedding climate change into risk management is challenging. One podcast episode had a deep dive on flood risk modelling, providing a useful framework for thinking about physical risk. This framework comprised three elements that will be familiar to many risk professionals:

(1) hazard (e.g., flooding);

(2) exposure (e.g., a building in a flood plain); and

(3) vulnerability (e.g., a building on stilts, which is less vulnerable to flooding).

Getting data on all three elements can be difficult. Firms might also find it hard to process available data, which will take investment to overcome. And it is challenging to backtest models (given a lack of data) and to decide how far climate risk should be incorporated into well-established risk measures, such as probability of default (PD). But there is an urgent need to get on top of these risks, which are happening faster than most in the investment community realize.

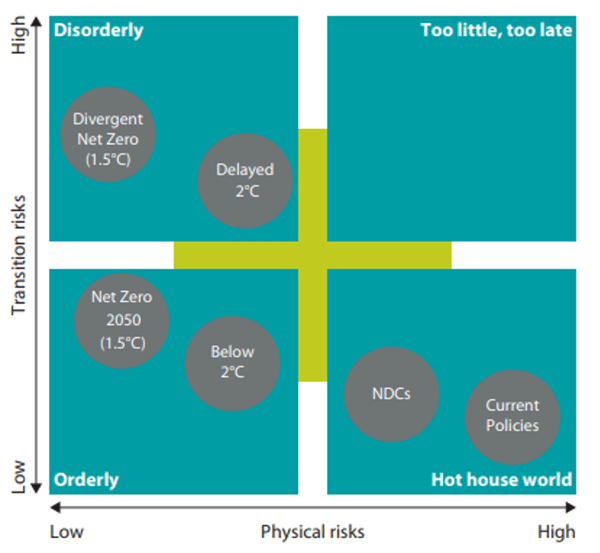

A key tool that risk professionals need to use is scenario analysis, as the future will not be like the past. We heard how many scenarios currently in use tend to be either (i) high physical and low transition risk, or (ii) high transition risk and low physical risk, as if there is some sort of trade-off between them. This is well illustrated by the scenarios produced by the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), as Figure 3 shows. The NGFS is a coalition central banks and supervisors that share best practices on climate risk management, making their scenarios the most commonly used ones across the financial sector.

Figure 3 NGFS Scenario Framework

Source: NGFS Scenarios for central banks and supervisors, 2022

But the longer we delay meaningful action to mitigate climate change, the more likely a high physical risk and high transition risk world becomes. One guest noted how the current generation of scenarios underplay the impacts of physical risks. For long-lived physical assets (e.g., construction projects), a high emission scenario can be helpful for planning purposes, as it is closest to the path we are currently on, but also arguably builds in an element of prudence.

Financial firms will need to assess their counterparties’ ability to navigate a period of rising physical and transition risk. While their own boards will need to be strategic, they will also need to assess the competence of boards of the firms that they are lending to, investing in or underwriting. Plan to transition too fast, and these firms might well lack credibility; go too slowly, and they might be criticized for lack of ambition and possibly greenwashing. A risk focus can help here. Risk professionals need to be particularly careful when net-zero commitments rely on carbon offsets, as the primary objective should be to reduce emissions, and we have heard in various episodes about concerns about the quality of offsets.

A key risk that risk professionals need to be aware of is greenwashing. Not only must financial firms not overstate their ‘green’ credentials, but they must also be careful to assess how green their counterparties genuinely are. This can be challenging. One approach to signalling sustainability is provided by the B-Corps movement, where firms meet certain criteria (which are externally validated) to prove their commitments to sustainable practices.

The lack of good quality data is a key concern for many risk professionals, often blamed on the plethora of different reporting standards. Moreover, these published reports do not always capture all the risks. This may be partly because TCFD is not mandatory. Indeed, one guest argued that frameworks such as TCFD can be a wasteful distraction, as firms do not publish material risks in these disclosures. Another guest noted how disclosures often omit information on lobbying efforts and are not integrated with the firms’ main financial accounts.

These issues will no doubt be helped somewhat by the establishment of the new IFRS Sustainability Reporting Standards. But that depends on how broad and demanding the standards are. That said, reporting standards are no substitute for policy action on climate change. Risk professionals will need to use their ingenuity to work around these challenges, no doubt looking to new sources of data and modelling approaches. But the task of addressing climate risks is urgent and won’t wait until all these issues have been fully resolved.

Parting thoughts

Many of our guests had excellent advice for risk professionals, emphasising the significant scope for them to help their firms navigate an increasingly complex and challenging landscape. A constant refrain is the need for a multi-disciplinary approach, as the issues are complex and interconnected. Certainly, that is the approach we have adopted on the podcast, examining climate and environmental risks from a range of different angles. The Climate Risk Podcast provides valuable insights on how the world of business and finance is changing and what this means for risk management. Listen in and give us feedback – we’d love to hear from you!

Jo Paisley, President of the GARP Risk Institute, has worked on a variety of risk areas at GARP Risk Institute, including stress testing, operational resilience, model risk management and climate risk. Her career prior to joining GARP spanned public and private sectors, including working as the Director of the Supervisory Risk Specialist Division within the Prudential Regulation Authority and as Global Head of Stress Testing at HSBC.

GARP’s Sustainability and Climate Risk (SCR) Certificate provides the foundation needed to tackle climate related risks and help prepare for future regulatory climate mandates.