A “cyber Pearl Harbor” scenario has haunted the technology world since then-U.S. Defense Secretary Leon Panetta presented it in 2012. The massive SolarWinds breach that came to light in December 2020 may have been it - or it may be a harbinger of even worse to come.

What is certain is that in the year when the coronavirus pandemic reigned as the most disruptive and overarching of societal and economic risks, this other, perennial emergency did not take a holiday.

Although perhaps drowned out by other headline news, there continued a steady stream of cybersecurity alarms. They were no less dire than in prior years, and as if to validate them, the SolarWinds hackers penetrated possibly thousands of government and business networks and triggered a coordinated “whole-of-government response to this significant cyber incident” by a Cyber Unified Coordination Group.

Nine months earlier, with the words “our country is at risk,” two U.S. Congress members - Senator Angus King, Independent of Maine, and Representative Mike Gallagher, Republican of Wisconsin - opened a cover letter introducing the report of the Cyberspace Solarium Commission, which they co-chaired. “The status quo in cyberspace is unacceptable,” asserted the 188-page blueprint for a national “layered cyber deterrence” strategy. More than 20 of its recommendations for public- and private-sector actions were written into the new National Defense Authorization Act, making it, in King's words, “the single most comprehensive piece of cybersecurity legislation ever passed by Congress.” (The NDAA became law when President Donald Trump's veto was overridden.)

On a global level, the World Economic Forum in November produced Cybersecurity, Emerging Technology and Systemic Risk. In a collaboration with the University of Oxford, WEF warned that by 2025, quantum computing and other next-generation technology “has the potential to overwhelm the defenses of the global security community.” The report recommended 15 “strategic interventions for individual and collective action, without which the global community risks creating an ecosystem that is not resilient to the emerging threat landscape and where cybersecurity could become a barrier to unlocking the full potential of technology and cyberspace.”

Damages and Reactions

Then came the shock: Russian agents are believed to have exploited SolarWinds Corp.'s widely used network monitoring software over a period of months in what appeared to be “the most serious cyber attack this country has ever endured,” Sen. King said in a December 17 radio interview.

“Simply assessing, let alone repairing, the damage will be a monumental undertaking,” said American Enterprise Institute resident scholar, Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies professor, and Bloomberg Opinion columnist Hal Brands.

Dmitri Alperovitch, a co-founder of security firm CrowdStrike who is now executive chairman of Silverado Policy Accelerator, said the full impact of the “spectacularly successful operation” will become clearer as more facts emerge - such as the belated revelation that some Microsoft source code was exposed.

Whether carried out for espionage or other purposes, the supply-chain attack has been characterized as a stunning intelligence failure, calling into question the effectiveness of two decades' worth of cyber defense buildups. Billions Spent on U.S. Defenses Failed to Detect Giant Russian Hack, the New York Times headlined, and “the remediation effort alone will be staggering,” former White House homeland security adviser Thomas Bossert said in an op-ed column.

The developing narrative is of a breakdown in management of a third-party risk in plain sight; a nation-state offensive that went undetected by a federal cybersecurity apparatus that had just recently boasted of its success in ensuring a safe presidential election; and shortcomings in a crucial intelligence-gathering mechanism - the sharing of threat information among government and business entities.

There is not, and never has been, a vaccine-like silver bullet on the cyber horizon. If there are rays of hope, they are in a consensus recognition of those weaknesses and resolve to remediate them - not impossible considering the strong, bipartisan clarion call of the Cyberspace Solarium Commission; stated intentions of the incoming Biden administration and NDAA mandates that include appointment of a Senate-confirmed national cyber director within the Executive Office of the President; increased international recognition of, and calls to action to address, the systemic implications of cyber risks; and improvements in information sharing.

Perceptions and Priorities

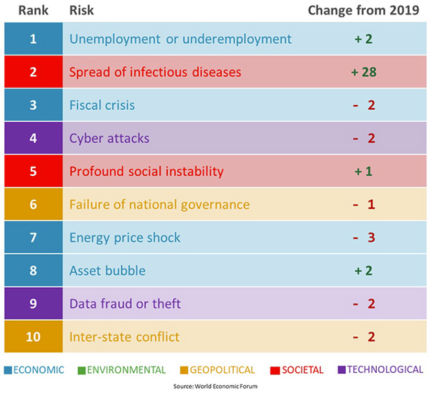

Cybersecurity, a top C-level and boardroom concern for years, was outpolled by the pandemic in the World Economic Forum Executive Opinion Survey, conducted in the first half of 2020. Although still high on the risk ranking, at No. 4 based on more than 12,000 survey responses from 127 countries, cyber attacks fell from second place in 2019. Unsurprisingly, infectious diseases shot up to second from 30th, trailing only unemployment or underemployment, and just ahead of fiscal crisis.

The “largely unchanged,” if somewhat rearranged, lineup of risks “attain[s] new significance in a COVID-19-impacted world,” said a commentary by WEF partner Marsh & McLennan. And prominent risks are in many respects interconnected, as is monitored in the WEF's annual Global Risk Reports each January and typified by the upsurge in cyber hacks, crimes and scams that paralleled the spread of the virus

“The pandemic is also forcing executives to pivot business models and operational practices in a physically distanced and digitally dependent world,” Marsh & McLennan added. “Increasing reliance on digital infrastructure has reaffirmed the dangers of cyber threats to businesses globally, with added criticality” - and cyber still ranked No. 1 in advanced economies, where infectious-disease spread came in second.

That was not the only survey indicating change in relative risk perceptions. In the Depository Trust & Clearing Corp. Systemic Risk Barometer, published in December, the pandemic was deemed a top-five risk to financial stability by 67% of 220 global respondents. That was well ahead of the 54% citing cyber risk - a figure that declined from 63% a year earlier.

Cyber issues did not figure directly in the Atlantic Council's top 10 risks for 2021, of which a “stifled” Biden presidency and slow economic recovery were “high probability” and a major world food crisis has “already arrived.” The policy think tank does track cybersecurity in an ongoing 2035 global risks scenario; has said that “in its early days, the incoming U.S. administration must take on cybersecurity threats as one of its key priorities,” particularly in concert with NATO allies; and the council's Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security recently assembled a panel of experts whose “cyber wish list” made multiple references to Cyberspace Solarium Commission and National Defense Authorization Act provisions.

No. 6 in geopolitical consulting firm Eurasia Group's Top Risks 2021, published January 4, is titled Cyber Tipping Point: “The Biden administration will attempt to stabilize the situation,” it says, “mainly by trying to improve U.S. government coordination on cyber responses. But a downturn in U.S.-Russia relations will be a key factor in making 2021 ripe for cyber trouble.”

None of this is to say that cybersecurity is any less of a priority. Such findings may only underscore the attention it requires and is attracting in geopolitical and business context, and in view of systemic risk and financial stability.

“Incentivize Collaboration”

The WEF's November report with University of Oxford flagged “hidden and systemic risks inherent in the emerging technology environment” and said, “Policy interventions are required that incentivize collaboration and accountability on the part of both businesses and governments.”

Another WEF report, back in July, turned a spotlight on fintech developments, noted that “cyber risk is pervasive, systemic and global in scope,” and said that mitigating it will require “a sector-wide baseline for cybersecurity . . . to ensure the integrity of the global financial system.”

In November, five years after launching a “FinCyber” study of financial system cyber resilience, and making note of an April 2020 Financial Stability Board warning that “cyber incidents pose a threat to the stability of the global financial system,” the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace published a 200-plus page International Strategy to Better Protect the Financial System Against Cyber Threats.

The Carnegie Endowment, acknowledging WEF as a partner, defines six priority areas - among them collective response and capacity-building - and proposes “overarching recommendations” to the G-20 heads of state (“create interagency processes within their respective governments”), financial services firms (“expand their engagement and dedicate more resources to strengthening the protection of the sector overall”), and G-7 finance ministers and central bank governors (renew the G-7 Cyber Expert Group mandate and expand “the number of participant states” along the lines of the anti-money-laundering Financial Action Task Force).

“Public Policy Objective”

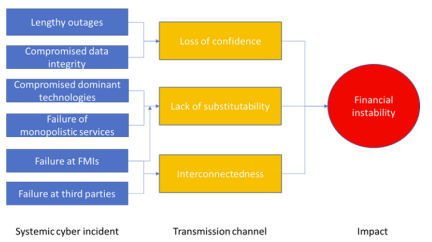

An International Monetary Fund staff discussion note, Cyber Risk and Financial Stability: It's a Small World After All, touches on risks arising from loss of confidence, lack of substitutability of services suffering outages, and interconnectedness via clearing, settlement and payments systems, lending, and other counterparty exposures.

“Cyber attacks can propagate not only through third-party technology service providers, but also through targeted clients, retail partners, or counterparties,” says the December IMF paper. “The cross-border nature of both financial and IT services also raises the risk of cross-border contagion from large-scale cyber attacks.”

Framing financial-sector cyber risk mitigation as “a key public policy objective,” the IMF authors “see a need for further work” and “significant scope to improve both the quantification of risks and the integration of cyber risk into broader financial stability analysis,” employing cyber mapping and stress testing techniques, along with reliance on regulatory and supervisory frameworks and information sharing.

“Pooling information on cyber risks can enhance situational awareness, help detect new risks, and build better responses,” says the IMF document. However, sharing by financial firms has been inhibited by regulatory barriers and liability concerns, and “limitations on information sharing, particularly across borders, can increase vulnerabilities because information silos can be exploited by cyber attackers, who are able to work across jurisdictions with ease.”

“Establishing a globally agreed template for cybersecurity information sharing using a common taxonomy would be helpful,” the report suggests.

Defense Is Not Enough

Remedies and responses have been evolving since the 1990s, with much official attention centered on the organization and coordination of relevant defense and homeland security, military and intelligence, law enforcement and regulatory agencies. The “unified coordination” response to SolarWinds, for example, is led by the FBI, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

Those bodies and the National Security Agency, in a joint statement January 5, said that “an Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) actor, likely Russian in origin, is responsible for most or all of the recently discovered, ongoing cyber compromises of both government and non-governmental networks.” They judged it to be “an intelligence gathering effort,” adding that “of the approximately 18,000 affected public- and private-sector customers of SolarWinds' Orion product, a much smaller number have been compromised by follow-on activity on their systems.”

Principles of cross-agency collaboration and removing bureaucratic silos have long been embraced, alongside channels of communication and interaction across borders and with the private sector. But the complexities have taken years to work through (see Force Multipliers for an Endless War), and frameworks like “layered cyber deterrence,” as laid out by the Cyberspace Solarium Commission, remain works in progress. The same can be said of battle tactics and rules of engagement - most experts agree that a static, purely defensive posture is not viable - and the all-important threat-intelligence and information sharing.

“The relatively open nature of the democratic internet, and the fact that responsibility for cybersecurity is diffused among so many public and private actors, creates vectors of vulnerability that will always tempt authoritarian regimes,” observes Hal Brands of Johns Hopkins.

Ian Bremmer and Cliff Kupchan of Eurasia Group write: “Geopolitically, governments and the private sector have made no headway in developing global rules for state behavior in cyberspace,” while “geopolitical rivalries among cyber capable states have also grown more acute . . .

“During the Trump administration, the U.S. granted its own cyber warriors more leeway to go on the offensive against malicious hackers. But despite claims of victory, there has been an increase in cyber efforts to steal vaccine research and gain access to government and critical infrastructure networks. The lack of a global effort to shore up systems and impose penalties beyond symbolic gestures such as sanctions and travel bans will continue to embolden bad actors this year.”

Advising that the response to SolarWinds “cannot be solely defensive,” Brands points out that the U.S. Cyber Command, which is led by the National Security Agency director, “has been pursuing a 'defend forward' posture that emphasizes keeping adversaries off balance by penetrating and, occasionally, disrupting their networks . . . In the wake of this attack, the U.S. must find subtle ways of showing that it can achieve equivalent or greater breaches of Russian networks - those used by Putin's security services and propaganda organs, for instance, or by financial firms that are linked to the Kremlin and handle the flow of dirty money that lubricates that regime.”

Codification of Strategy

The Cyberspace Solarium Commission sought more formal codification of both government and commercial-sector operational latitude and flexibility, reflected in several National Defense Authorization Act provisions. Sen. Angus King has pointed out that the law will allow CISA to “'threat hunt' on government networks. That is, to test, to try to penetrate them, to try to hack them, to find where the vulnerabilities are.”

Other accepted commission recommendations included: a “Continuity of the Economy” planning effort, applying to government operations and “systemically important critical infrastructures”; establishment of a “Joint Cyber Planning Office under CISA, to facilitate comprehensive planning of defensive cybersecurity campaigns across federal departments and agencies and the private sector”; sector-specific “risk management agencies, establishing minimum responsibilities and requirements for identifying, assessing, and assisting in managing risk for the critical infrastructure sectors under their purview”; and “assessing private-public collaboration in cybersecurity . . . and make recommendations for improvements.”

The commission stressed the importance of private-sector engagement by titling one of the six “pillars” of its strategy “Operationalize Cybersecurity Collaboration with the Private Sector.” The report said it is up to the government to “support and enable the private sector. The government must build and communicate a better understanding of threats, with the specific aim of informing private-sector security operations, directing government operational efforts to counter malicious cyber activities, and ensuring better common situational awareness for collaborative action with the private sector.

“Further, while recognizing that private-sector entities have primary responsibility for the defense and security of their networks, the U.S. government must bring to bear its unique authorities, resources, and intelligence capabilities to support these actors in their defensive efforts.”

Information Cooperation

The Cyberspace Solarium Commission positioned information sharing as a key element of its Joint Cyber Planning Office proposal, and the commission's report held out as a private-sector case example the Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center (FS-ISAC), one of the oldest and largest of some two dozen such organizations serving critical-infrastructure industries.

“Pooling information on cyber risks can enhance situational awareness, help detect new risks, and build better responses,” says the IMF staff report, which, along with the Carnegie Endowment, noted the emergence of such other collaboration initiatives as the Bank for International Settlements' Cyber Resilience Coordination Centre; European financial market infrastructures' Cyber Information and Intelligence Sharing Initiative; the Financial Sector Cyber Collaboration Centre in the U.K.; Pathfinder, which links the U.S. financial services sector, Treasury Department, the military and Cyber Command; and the Financial Systemic Analysis & Resilience Center, an FS-ISAC offshoot that connects major U.S. financial institutions with the Departments of Defense, Homeland Security and other key agencies.

Adding in the Financial Services Sector Coordinating Council, the Coalition to Reduce Cyber Risk and Cyber Risk Institute reinforces the impression of an industry that has its information-sharing bases covered. It was also relatively unscathed by SolarWinds: “Based on what we have seen as of today, there has not been specific focus against the financial sector, nor have we seen reports indicating negative impact amongst our members,” FS-ISAC said in a statement reported by Bloomberg on December 18.

Still, there are perceived flaws. The IMF paper says that in addition to assuaging legal concerns, international cooperation is critical: “Limitations on information sharing, particularly across borders, can increase vulnerabilities because information silos can be exploited by cyber attackers, who are able to work across jurisdictions with ease.”

The World Economic Forum, in its “forward look” at advanced technologies, anticipates that “intelligence sharing at the pace necessary to address emerging threats” will become even more daunting: “A range of current operational capabilities will be challenged. Information-sharing models need to evolve to keep pace with the increasing scale and complexity of the technology and threat, for example.”

FS-ISAC, which has headquarters in Virginia and a global membership, announced in December the signing of a memorandum of understanding to support anti-fraud efforts of the European Association for Secure Transactions. “Accelerated global digitalization combined with the growing sophistication of cyber criminals demands more sharing and collaboration in the financial sector, both regionally and globally,” said Lucie Usher, FS-ISAC's intelligence officer for EMEA. The strengthened collaboration “will further enable intelligence sharing to better safeguard both the European and global financial system.”

Also active multinationally is the Global Resilience Federation, which “serves as a hub for cross-sector cyber, physical and geopolitical intelligence sharing and analysis from information sharing and analysis centers (ISACs), organizations (ISAOs), computer emergency readiness/response teams (CERTs), private vendors and government.” With former FS-ISAC chief executive Bill Nelson as chairman and CEO, GRF has, among other moves, announced relationships with F-Secure in threat detection and response, RiskAnalytics in threat intelligence and BSS Unit in threat hunting.

“This is an excellent match for GRF's mission to protect organizations by facilitating centralized, multi-sector exchange of actionable intelligence,” Nelson said of F-Secure. “We can help this research reach organizations in important industries that need to preserve public trust.”

Underappreciated Results

Jeanette Manfra, who was assistant director for cybersecurity at CISA before leaving at the end of 2019 to become global director of security and compliance for Google Cloud, concedes that government and industry “can be more aligned,” but says fruits of cooperation are not fully appreciated because it happens away from public view. She believes that private companies on the whole have come to equal or exceed government as sources of threat intelligence.

CISA, a part of the Department of Homeland Security whose director, Christopher Krebs, was