What Are Physical Climate Risks and How Are They Changing?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), established in 1988, is the most authoritative source on the science behind climate change. It publishes comprehensive Assessment Reports about knowledge on climate change, its causes, potential impacts and possible response options.

Jo Paisley

The IPCC noted in its Sixth Assessment that it is “unequivocal” that human action has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land. This warming is caused by the release of greenhouse gases (GHG) into the atmosphere. The most prevalent of these gases is carbon dioxide (CO2), associated with burning fossil fuels, industrial processes, agriculture, forestry and other uses of land. But other gases — such as methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) — are also major contributors.

The IPCC notes many records are being set, including:

- The concentration of CO2 is at its highest level in at least 2 million years

- The sea level is rising at its fastest rate in at least 3,000 years

- Glaciers are retreating at a rate unprecedented in at least 2,000 years

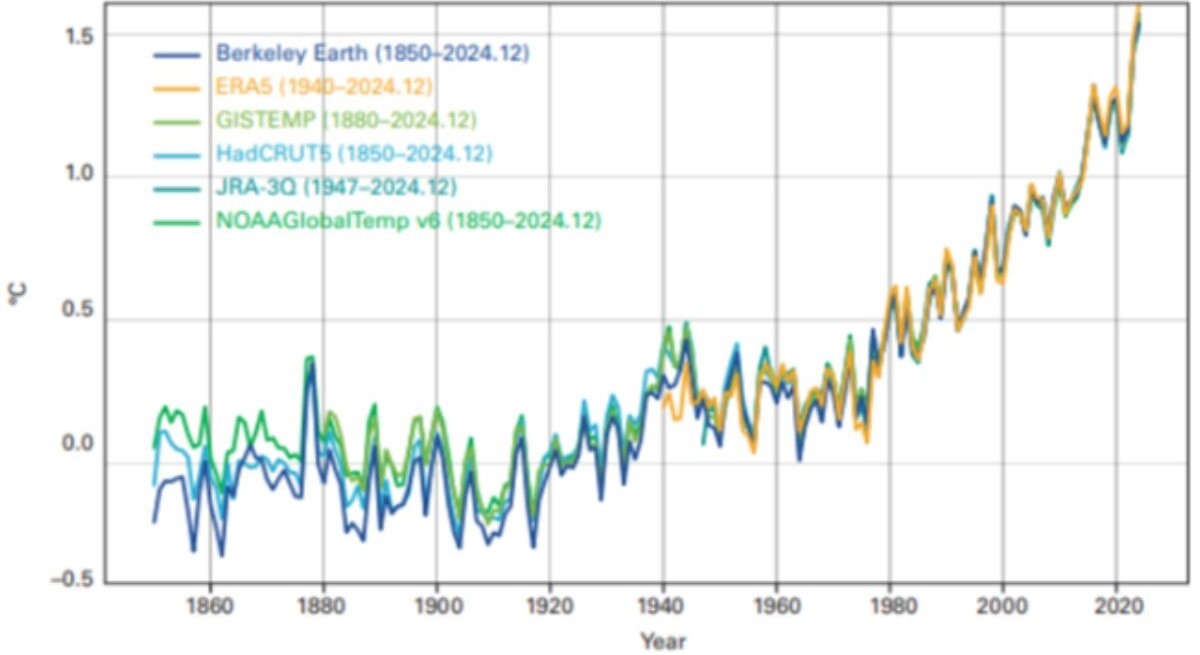

Since that report was published in 2021, emissions and average temperatures have continued to increase (Figure 1). In fact, 2024 was the warmest year on record globally. It was also the first calendar year that the average global temperature exceeded 1.5°C above its pre-industrial level (which is defined as the average over the period 1850-1900). While a one-year exceedance hasn’t breached the Paris Agreement target, the current rate of warming of more than 0.2°C per decade indicates we are on the way to doing so.

Figure 1. Annual Global Mean Temperature Increase Above Pre-Industrial Levels

Source: World Meteorological Organization State of the Global Climate 2024

How Does the Changing Climate Create Physical Risks?

Global warming is already producing many physical impacts, and they are expected to get worse. Examples are more frequent and intense heatwaves, more extensive wildfires, more droughts and also more extremely heavy rainfall, reductions in Arctic sea ice, snow cover and permafrost.

These physical impacts from climate change will feed through to an economy in a variety of ways, including damages to physical assets through extreme weather, reduced productivity (particularly in agriculture), heat-related illnesses and death, and loss of biodiversity. We can also expect supply chain disruption to become more routine, with damages to the physical infrastructure and possibly impacts on financial stability if the disruption is large enough.

To understand the drivers of these impacts it’s helpful to distinguish between the two main types of physical risks, namely acute or chronic:

- Acute physical risks are driven by specific weather events such as heatwaves, floods, wildfires and storms.

- Chronic physical risks are driven by longer-term shifts in climate patterns, such as rising sea levels and increasing mean temperatures.

As with transition risk, the hazards (events such as storms and heatwaves, or consequences of long-term shifts such as coastal flooding) will not translate into risks unless there is an exposure and vulnerability.

Exposure here is used in the traditional sense of companies and their assets located in a place that is susceptible to being impacted by these hazards, for example a manufacturing plant built in a low-lying coastal zone.

Vulnerability refers to a propensity to be adversely affected by a particular risk driver. For a physical asset, vulnerability will depend on the way that it has been built, for example, the material used, its elevation and any adaptation undertaken (such as insulation, water pumps or air conditioning). Two properties located on the same road may have very different vulnerabilities simply because of the way they have been constructed or adapted.

Physical Risks Are Wide Ranging

Firms can be exposed to physical risks either directly or indirectly. For example, a factory might be directly impacted by being in an area that is becoming increasingly prone to flooding. But even if the factory itself is well protected from floods and other hazards, it could be indirectly impacted if its supply chain is affected.

A good example of the type of disruption that can occur from physical hazards is provided by the floods in Thailand in 2011. These directly affected computer hard disk drive manufacturers and car manufacturers. But the disruption to the hard disk drive manufacturers rippled out, impacting the producers of electronic goods in a range of companies — from phone manufacturers to electronic equipment manufacturers in the European Union, Japan and the United States. The World Bank estimated that there were USD 45.7 billion of financial losses during the 2011 Thailand floods.

Cities, which tend to be the focus of much economic activity, are very susceptible to the impacts of climate change. For example, the changing climate is altering the water cycle, resulting in more extreme wetting and drying. This can have devastating impacts on cities, particularly those in low-income countries. Some experience “climate whiplash", where “droughts that dry up water sources [are] followed close by floods that overwhelm infrastructure, destroying toilets and sanitation systems, contaminating water” and spreading disease. Other cities are experiencing complete reversals of their usual weather patterns, with heavy rainfall in historically arid places, and places that are used to flooding now facing unexpected droughts. This will affect companies and their staff and customers directly, but also their supply chains.

The Non-Linear, Cascading, and Interconnected Nature of Physical Risks

A further complexity with calculating the physical risks from global warming is that the impacts are very likely to be non-linear. Some systems (be that human, ecological or man-made) might start to break down or stop functioning efficiently when they breach certain thresholds — the so-called tipping points.

There are also likely to be cascading risks from climate change. For example, the World Meteorological Organization, has noted how extreme weather is increasing the pressure on people to move: events in 2024, for example, led to the highest number of new displacements recorded since 2008. These events not only destroy homes, critical infrastructure, farmland, forests, and biodiversity, but also lead to a variety of compounding impacts, such as worsening conflict, and exacerbating droughts leading to crop failure and high domestic food prices and resulting food crises.

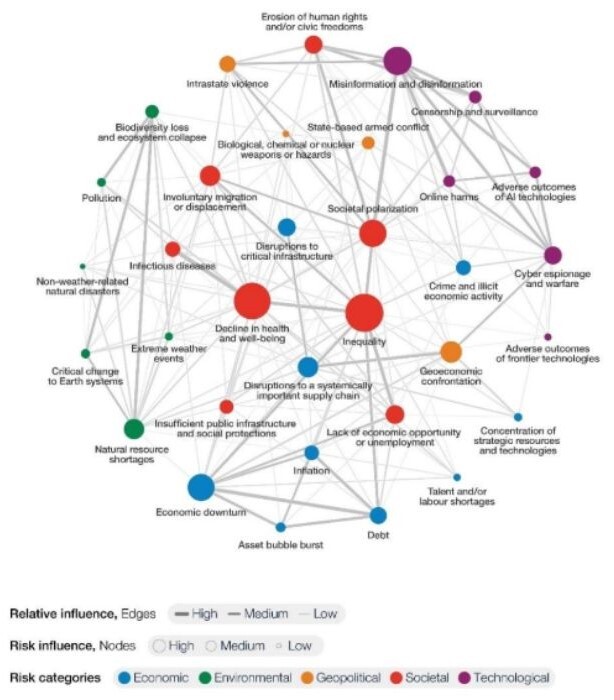

Climate and environmental risks are also very much interconnected to other risks, well-illustrated by the World Economic Forum’s latest Global Risks Report (Figure 2), which shows how experts see the interrelationships between the key risks facing the world.

Figure 2. Global Risk Landscape: An Interconnections Map

Source: World Economic Forum, Global Risks Report 2024-25

Of the environmental risks (shown in green), extreme weather events, biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse, critical change to earth’s systems and natural resource shortages, are regarded as the top four most severe risks facing the world over the next 10 years. These interconnected risks can cascade and amplify the impact of a physical event in complex and unpredictable ways, for example, by disrupting critical infrastructure and reducing human health and wellbeing. Once these amplifications are factored in, the headline temperature increase can be a misleading indication of the risks involved.

How Will Physical Risks Evolve?

A key factor influencing how physical risks will evolve is the path of future emissions. The UN Emissions Gap Report 2024 highlights the significant gap between the ambition of countries’ National Determined Contributions (NDCs), and the emissions reduction needed to meet the Paris Agreement ambition. According to that report, current promises put us on track for best-case global warming of 2.6°C this century.

However, there is considerable uncertainty around these trajectories. Some commentators argue that the NDCs understate the true pace of the transition. On the other hand, with the U.S. withdrawing from the Paris Agreement, there is the risk of losing momentum on cutting emissions.

It’s also worth realizing that as cumulative CO2 emissions increase, natural land and ocean carbon sinks become less effective at sequestering carbon. So, the proportion of emissions absorbed by land and ocean decrease. We are already seeing this; in 2023 there was an ‘unprecedented weakening of land and ocean sinks’ resulting in net CO2 increasing more than the increase in emissions.

Given all this, it’s perhaps not surprising that many countries are incorporating climate considerations within their national defense strategies as they recognise the growing influence of physical risks on their security and resilience, which will become even more important if they believe that emissions will not be cut in line with the Paris Agreement.

What Do Companies Need to Do?

Companies need to consider how both to mitigate their impacts on the climate, as well as to consider how they might be vulnerable to the impacts, which might require adaptation. For financial institutions, this means understanding how the companies they lend to, insure and invest in are impacting the climate, as well as being impacted by it.

Physical risk has not been as high a priority as transition risk for many financial firms according to our own research on climate financial risk management. This might reflect a perception that physical risks are more remote. But with increasing evidence of intensifying physical risks, boards would be wise to move this up their agendas.

For firms grappling with how to start understanding the physical risk in their portfolio, in 2024, the U.K.’s Climate Financial Risk Forum (CFRF) published a useful framework for considering how to utilise scenario analysis to assess adaptation needs and opportunities, with a range of scenarios recommended for use over different time horizons.

Parting Thoughts

With increasing physical risks happening now and the expectation that they will only intensify over coming decades, it’s clear they must be embedded into the risk assessments of business activities and planning, particularly for long-term strategy, assets and liabilities. But the most urgent action needed from financial institutions is to finance cutting emissions as soon as possible to prevent the accumulation of devastating systemic risks over coming decades.

For more insights on physical risk, these podcasts provide a useful introduction:

- Uninsurable: The Future of Insurance in a Changing Climate

- Urban Resilience: How Our Cities Must Adapt to Climate Change

- Why Extreme Climate Physical Risks Are Closer Than You Might Think

Jo Paisley, President, GARP Risk Institute, has worked on a variety of risk areas at GARP Risk Institute, including stress testing, operational resilience, and model risk management. Her focus is now climate and environmental financial risk management. She hosts the GARP Climate Risk podcast. Her career prior to joining GARP spanned public and private sectors, including working as the Director of the Supervisory Risk Specialist Division within the Prudential Regulation Authority and as Global Head of Stress Testing at HSBC.

GARP’s Sustainability and Climate Risk (SCR) Certificate provides the knowledge and skills needed to tackle climate related risks and help prepare for physical risk.

Topics: Physical Risk, Climate Risk Management