What is causing transition risk?

Before examining the main categories of transition risk, it is helpful to put the transition to a low-carbon economy in context.

According to the latest IEA data, global greenhouse gas emissions reached their highest level in history in 2021, rebounding after the COVID-19-induced reductions in 2020. Emissions rose particularly sharply in China, reflecting increases in demand for electricity that was generated from coal. Emissions also rose in India, which, like China, uses substantial amounts of coal-fired electricity. Elsewhere, there are signs that emissions are beginning to decline. Nevertheless, there remains an enormous challenge to ‘close the gap’ to net zero, as the United Nation’s (UN’s) 2021 Emissions GAP report makes clear.

Jo Paisley

Countries that signed up to the Paris Agreement pledged to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C and pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. A track to limit global warming to 1.5°C will require cuts in net global emissions of 45% from 2010 levels by 2030, and 100% by 2050.

Decarbonization on this scale implies unprecedented structural changes in economies, including major changes to the allocation of capital and the flow of financial investments. Each year we delay action to reduce emissions, the more we are backloading the problem. And this means increasing the risks of a ‘disorderly’ transition in which the speed of economic and social changes needed is faster, and the costs and risks associated with the transition are higher.

The 4 main drivers of transition risk

The original recommendations report of the Task Force on Climate-Related Disclosures (TCFD) set four main drivers of transition risk:

1) Policy and legal risks

There are many sources of policy and legal risks which will impact firms in a variety of ways, depending on the sector in which they operate, the carbon intensity of their operations, and their ability to adapt their business models. The thrust of many countries’ policy frameworks will be focused on shifting economic activity away from those dependent on fossil fuels to activities which have much lower emissions. Common policies include:

-

Switching electricity generation away from fossil fuel to renewables

-

Introducing carbon taxes, so that the ‘externalities’ (for example, pollution and climate change impacts) associated with fossil fuels are priced effectively

-

Mandating climate-related disclosures to promote transparency in markets regarding the risks and opportunities from the transition

-

Policies to improve energy efficiency and to increase natural sequestration (e.g. planting more trees, which act as carbon ‘sinks’ to soak up carbon emissions)

There is also a rising tide of many different types of climate-related litigation. These include claims against directors or companies for contributing to climate change, situations concerning a firm’s failure to consider emissions, and cases that accelerate climate actions and complaints against ‘greenwashing’. For more insights, listen to the GARP Climate Risk Podcast on The Rising Tide of Climate Litigation.

2) Technology

Technological advances have the potential to help speed up the transition to a low-carbon economy. This means that firms that are reliant on old, fossil-fuel technologies will be ripe for disruption unless they can adapt their businesses. There are also technological advancements improving the resilience to climate change (e.g. climate-resilient infrastructure). In addition to the significant commercial opportunities that technology offers firms and investors, there is also the risk that the technology is not widely adopted or proves unsuccessful.

3) Market changes

The transition to a net-zero economy will involve changes in the supply and demand of goods, and services and commodities, as well as shifts in their relative prices. Firms that adapt to this complex and dynamic context will navigate the transition more successfully than those that do not understand the nature of these changes.

4) Shifts in consumer and investor sentiment

Climate change is a potential source of reputational risk for firms as consumer and investor perceptions change. As consumers become more aware of the impacts of climate change, they may demand more climate-friendly products. Firms that are seen as climate ‘laggards’ may be at risk of a reputational backlash. Investor awareness and expectations for firms are also rising, with a number incorporating climate-risk considerations into their investment decisions.

How will transition risk impact firms?

How these drivers impact firms will depend on the types of exposures and vulnerabilities companies have and how these drivers evolve. Let’s look at these factors in turn:

1) Exposure and vulnerabilities of sectors and firms

Economic sectors will be impacted differently by transition risk depending in part on the intensity of their emissions, as well as the ability of firms to mitigate their emissions and adapt their business models.

The sectors of the economy most exposed to transition risks are those which have a relatively high carbon intensity, or those which operate in the supply chains of these sectors. For example, there is a great deal of innovation in transportation, with growth of electric vehicles and research and development on other forms of low-carbon transportation (e.g. hydrogen fuel cells). Firms that either manufacture internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles — or supply to these manufacturers — will need to adapt or face obsolescence. Companies with ICE fleets risk these assets becoming ‘stranded,’ where either policy changes or technological advances result in assets becoming uneconomic and written off prematurely.

Some sectors are energy intensive but ‘hard to abate’ in the sense that there are no obvious, economically viable, low-carbon alternatives at present. These include sectors such as petrochemicals, aluminium, steel, cement, and fertilizers. Within these sectors, lower cost operators will be at an advantage when dealing with policy changes such as carbon taxes. Policy changes will make some firms uneconomic. Longer term, firms that introduce economically viable low-carbon technologies will enjoy a significant commercial advantage.

Within sectors, a key factor determining the impact of the transition on a particular asset or firm is its vulnerability. The vulnerability of an asset or firm to transition risk refers to its propensity to be negatively affected by its exposure to a risk driver. For example, a company that is highly dependent on fossil fuels has a far higher vulnerability to transition risk (e.g. via the introduction of a carbon tax) than one that is already carbon neutral. Thus, a firm that is heavily dependent on fossil fuels but has a robust plan to decarbonize will be less vulnerable to climate policies than one that is not prepared for the transition. The Transition Pathways Initiative provides a useful tool, benchmarking companies across sectors on the quality of their management of climate risks and opportunities as well as their carbon performance.

Since they have relatively low greenhouse gas emissions from their business operations, the main transition risks that will impact financial institutions are from the impact of the transition on their counterparties (that is, the firms that they lend to, invest in and/or insure such as companies and households) and the assets they manage. Certainly, transition risk is high on the agenda at financial firms. GARP’s Third Annual Climate Risk Management Survey indicated that transition risk is a higher priority at more firms than physical risk or portfolio alignment.

2) The evolution of transition risks

The evolution of these four sets of drivers of transition risk is highly uncertain. In part, this reflects the significant uncertainty over the future path of emissions. As the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) points out in their report on Climate-related risk drivers and their transmission channels, “Empirical evidence of the impacts of transition risk drivers, as with physical risk drivers, is limited. Instead, researchers and supervisors have relied upon scenario analysis to establish the range of these path-dependent economic effects.”

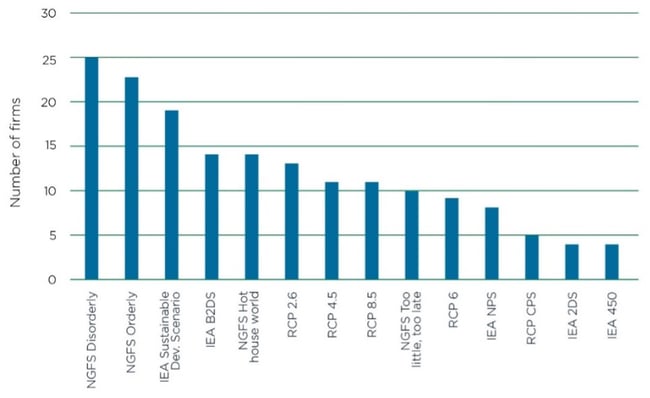

The GARP Risk Institute’s deep dive on climate scenario analysis practices in financial firms as part of the Climate Financial Risk Forum‘s 2021 outputs, showed that firms use different scenarios to analyze different risks. The most popular scenarios to explore transition risks were the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) disorderly and orderly transition scenarios (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Most Common Scenarios to Assess Transition Risks

These scenarios will be associated with different impacts on firms, depending in large part on the profile of the transition, as embodied in the economic variable profiles such as GDP growth, carbon taxes, adoption of new technologies, unemployment, and other factors. For a given temperature outcome, a scenario in which the transition is delayed is more costly to the economy than one in which there is an earlier, more orderly transition. That is because the policy response in a delayed transition needs to be more abrupt, which tends to result in more economic disruption than one in which policy changes are well signposted so those who will be affected can plan and adapt.

Looking to the future

Although embedding climate financial risk into financial firms’ risk management frameworks remains a work in progress, we see evidence of a growing level of sophistication at the leading firms. With carbon emissions continuing to increase and transition risks rising in tandem, it is increasingly important for firms to start investing in their climate risk management capabilities.

Jo Paisley, President of the GARP Risk Institute, has worked on a variety of risk areas at GARP Risk Institute, including stress testing, operational resilience, model risk management and climate risk. Her career prior to joining GARP spanned public and private sectors, including working as the Director of the Supervisory Risk Specialist Division within the Prudential Regulation Authority and as Global Head of Stress Testing at HSBC.

GARP’s Sustainability and Climate Risk (SCR®) Certificate provides the knowledge and skills needed to tackle climate related risks and help prepare for transition risk.

Topics: Transition Risk, Climate Risk Management