Market participants still holding U.S. dollar Libor-based financial products have until June 30, 2023, to transition them to a replacement benchmark rate, and this year’s interest rate volatility has stymied the preferred route of refinancing Libor transactions into another benchmark. Instead, they could find themselves clamoring in the time remaining to remediate transactions’ contractual language, an approach that anticipated Federal Reserve rulemaking may resolve in some cases while complicating others.

All new floating-rate transactions were required to use a Libor replacement rate from January 2, 2022, with syndicated loans and other products adopting the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) or alternatives such as Ameribor.

Meredith Coffey, executive vice president of research and co-head of public policy at the Loan Syndications and Trading Association (LSTA), noted that according to Fitch’s Covenant Review, 34% of loans in the Credit Suisse Leverage Loan Index have “hardwired” fallback language that will transition them to a replacement rate by the end of June. Fifty-six percent will have to be amended to fall back, a process Coffey described as relatively streamlined, but not a cakewalk.

“This is going to be challenging from operational and legal standpoints,” she said. It is a question of having “the bandwidth and people to actually do these amendments.”

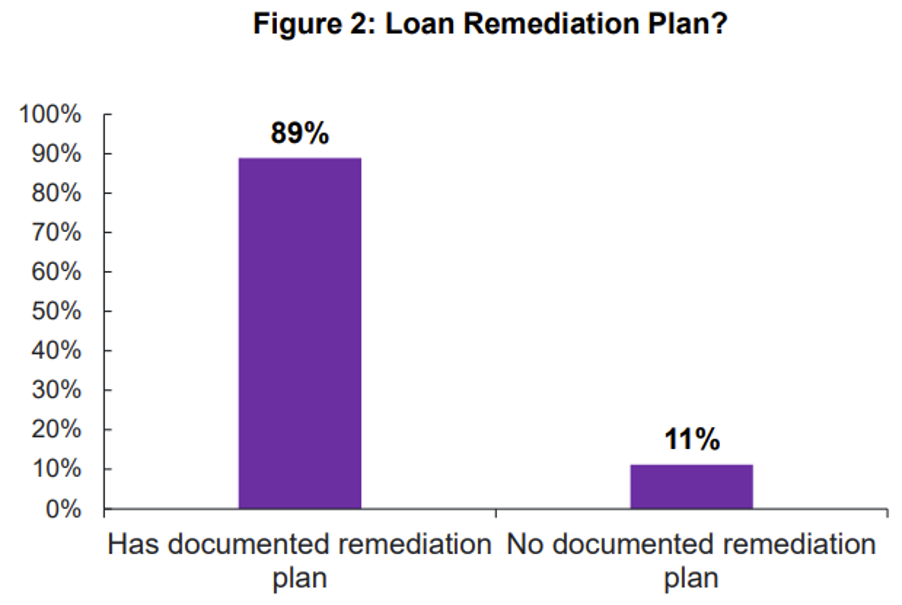

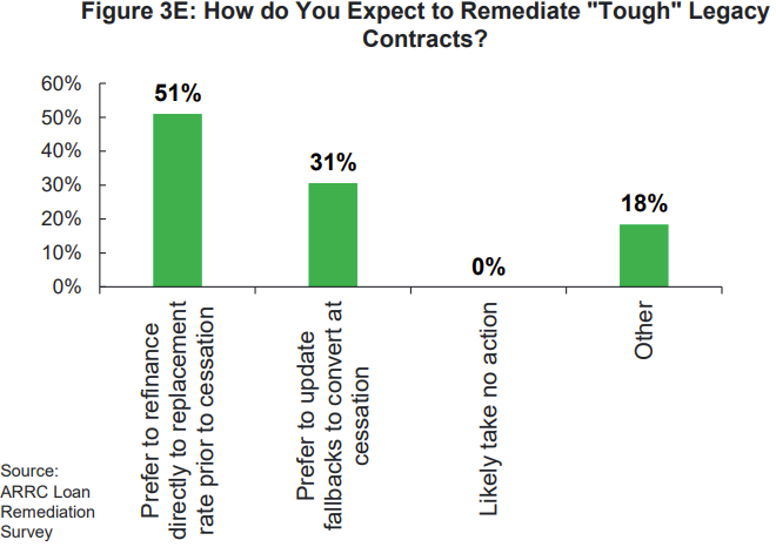

According to a survey of 70 lenders and borrowers by the Alternative Reference Rates Committee (ARRC), the Federal Reserve-sponsored industry group that is behind SOFR, 90% have documented plans in place to remediate those Libor-based loans. It also found that 55% intend to refinance directly into a Libor replacement rate prior to Libor cessation, and 51% said that is the preferred route to remediate “tough” legacy contracts that have either insufficient fallback language or none at all.

Of survey respondents without a documented remediation plan, three-fourths were borrowers. (Figures are from the ARRC Loan Remediation Survey.)

Work Cut Out for Borrowers

Coffey said it is not surprising that of those without a documented plan, three quarters are borrowers. They typically have at most a handful of Libor loans on their books. Whether they have a documented plan or not, those transactions must be transitioned, and that appears likely to be a major task.

Only 15% of all loans are currently priced over SOFR, the rest still on Libor, according to Coffey, and market volatility this year has stalled the refinancing route that the majority have chosen.

Coffey pointed out that the Morningstar LSTA US Leveraged Loan 100 Index shows loans have traded below par for most of the year. That has resulted in few corporate borrowers opting to refinance loans opportunistically, before they mature, since they would have to significantly increase the yield provided to investors on the new debt to approximate what they’re now receiving on existing debt in the secondary market.

“So that organic refinancing into SOFR that we were hoping to see has not shown up,” the LSTA executive said.

That leaves borrowers to decide whether to bet on the return of a more attractive market to refinance between now and June, or pursue the amendment route.

In the ARRC survey, 55% of borrowers had been contacted by their lenders about the Libor transition on all their loans, to pursue either early refinancing or a fallback amendment to a replacement rate. Another 35% said they had been contacted about only some of their loans, and 10% had yet to be contacted.

Borrowers should consider remediating loans sooner rather than later, even if markets remain choppy, Coffey said. A borrower may have only a few loans to remediate, “but if you’re in the queue with thousands of your corporate peers, it’ll be a lot harder to do.”

The Libor Act

Signed into law by President Joe Biden last March, the Adjustable Interest Rate (Libor) Act addresses the likelihood some Libor transactions will not be refinanced or appropriately remediated in time. It establishes a uniform process to transition those transactions when Libor ceases.

Ilene Froom, a partner at Katten Muchin Rosenman, described the law as an important legal mechanism to resolve those problematic transactions, such as floating-rate notes with many investors that issuers would have to find to sign amendments. However, she said, parties to Libor transactions should rely on the law as a last resort.

“The legislation is a safety net but should not result in parties putting their pencils down until June 30, 2023,” Froom said. “Having executed, agreed-upon amendments in place can also avoid disputes as parties determine how and whether the Libor Act applies to their contracts.”

The Federal Reserve was required to promulgate rules implementing the act by September 11. The complexity of the task, and potentially several intersecting rules, has delayed the effort.

Although the rule will play a significant role in transitioning away from Libor before the deadline, the Fed’s rulemaking, for which comments were due in August, could bring some loans back into scope of the law, Coffey said in a September 6 note to LSTA members.

A Fed-FCA Difference

The U.K. Financial Conduct Authority initiated a consultation into whether to compel the publication of a “synthetic” Libor after the benchmark ceases, to give non-U.S. governed USD Libor contracts currently without workable fallback language more time to remediate. But the Fed said a synthetic Libor could cause ambiguity, and it proposed specifying that the contractual replacement mechanism take effect on the Libor replacement date.

The LSTA recommended avoiding the Fed’s approach, because it could pull contracts that are intentionally not subject to the Libor Act back into its scope, with unintended consequences.

“The Fed’s synthetic Libor solution could require contracts to transition regardless of whether they are subject to the Libor Act, thus forcing loans that would otherwise go to synthetic Libor to transition to their fallback, such as the prime rate,” Coffey said. She added that it would compound the confusion, and moving to the prime rate could be more costly.

In addition, under the current Fed proposal, banks could potentially lose a safe harbor protecting them from legal disputes in transitioning away from Libor contracts – typically on contracts other than loans that are not covered by the Libor Act – that have inadequate fallback language.

Coffey said the Libor Act intentionally covers some contracts and not others, but the Fed’s proposal defines covered and noncovered contracts somewhat differently.

As a result, parties may transition their transactions exactly how the Fed prescribes, such as moving to term SOFR plus the spread adjustment recommended by the ARRC. But although they’ll be protected under the Libor Act, a contract not “covered” under the Fed rule could lose safe-harbor protection.

“That’s a nontrivial ramification,” Coffey said.

Topics: Financial Markets