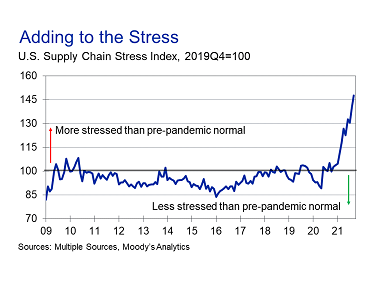

Supply-chain failures, and their knock-on effect on inflation, have risen to the top of the list of economic concerns for both households and businesses. Their fears are well-grounded. As the world economy reawakens, the Moody’s Analytics Supply Chain Stress Index recently reached an all-time high.

We can add supply chains to the growing list of “somewhat predictable but far from expected” events over the past year. This troubling list includes a global pandemic, a heatwave in Canada, killer floods in Northern Europe, and a plague of scorpions in Egypt.

One approach that risk managers can take to manage these types of extreme events is threat assessment and mitigation. As risk professionals, we should be constantly monitoring the landscape for emerging hazards, assessing the probability that they will impact our specific businesses or portfolios. Simultaneously, we need to run scenario analysis regularly to quantify the severity of selected shocks.

Cristian deRitis

However, we can’t assess every possible threat with this type of deep analysis. Even if we could, it’s unlikely that we would take many pre-emptive mitigation steps, given the small probability of a tail-risk event occurring in any given period.

COVID-19 is a case in point. In the wake of SARS, Ebola, and other outbreaks, a global pandemic had been on the radar screens of risk managers for a while. But is an institution going to radically change its portfolio strategy based on an event that has less than 1% probability of happening in any given year?

Even when managers have a high conviction about a potential tail event, shareholders may be reluctant to give up short term gains to guard against a remote risk that may or may not materialize. So, then, what’s the solution?

The Power of ESG: Resilience is Not Futile

A more effective and palatable approach for risk managers looking to guard against tail events is to focus on institutional agility and resilience. We may not be able to predict the timing or nature of a shock, but we can ensure that we are able to respond quickly and effectively when disaster strikes.

Given this objective, how can a creditor assess the resiliency of the businesses within their lending portfolio? Until recently, measures were either unavailable or narrowly defined by industry or sector. Credit risk analysis focused primarily on financial statement data, supplemented by broad classifications of “high-quality” or “low-quality” firms.

This reality has been altered, however, by measures that consider a firm’s environmental, social and governance (ESG) footprint. The availability of ESG scores covering both large and small firms provide an excellent proxy for institutional resilience across industries.

Research conducted by Moody’s Analytics shows that firms with higher ESG scores are less likely to experience negative events in the future and more likely to have higher stock prices. Based on Merton’s distance-to-default model, higher equity values are correlated with lower losses.

ESG, therefore, isn’t just a “feel good” investing fad. Rather, it has measurable credit risk outcomes that investors, lenders and other risk managers can leverage to their advantage.

Consider the risk posed by a business with sloppy bookkeeping or lax financial controls. All else being equal, this firm poses higher credit risk relative to a peer without these issues. This difference could be captured, and investment dollars could be allocated more appropriately, with the help of a standardized assessment of governance practices.

But the “G” in E.S.G. scores goes beyond measures of accounting and disclosure transparency to include metrics on board and management diversity by age, gender and expertise.

Diverse firms may be more likely to appreciate emerging market trends and shifts in demand. Indeed, studies suggest that culturally-diverse firms may be more innovative, have higher employee retention, and make better decisions than non-diversified companies. While diversity isn’t the only consideration, it can be an important risk factor when deciding whether to loan funds or invest in a company.

Similarly, the social component in the ESG framework extends to all social and human capital-related activities – including product safety and data security. Supply-chain vulnerabilities are explicitly considered by the “S” in E.S.G, as they may expose a business to disruptions in production. This in turn may lead to higher credit risk, which would be impossible to detect from financial performance alone.

Although environmental risks are generally not considered in textbook credit risk models, recent real-world experience highlights the consequences of this deficiency. The number and severity of acute physical climate events (such as hurricanes and floods) have risen dramatically, with direct economic impact on property owners, lenders and insurers. Fortunately, in recent years, credit risk modelers have been able to better account for these physical threats, thanks to the availability of data and climate risk tools.

Transition and adaptation risks connected to companies’ efforts to reduce their carbon footprints are more difficult to model. Risk modelers can, however, assess the overall vulnerability of companies to new climate regulations – the next best thing to modeling transition and adaptation threats directly.

We can, for example, measure carbon emissions or energy efficiency to assess how easy it would be for a firm to comply with new rules. Firms with an inability to pivot will naturally pose a higher credit risk.

Parting Thoughts

Whether we are talking about individuals, businesses or countries, few would dispute that character qualities – such as agility, resilience or grit – matter as predictors of future success. The challenge for investors and risk managers has always been measurement.

How can we quantitatively assess these qualities in a way that is both consistent and comparable? Prior attempts with surveys or checklists have been inadequate, given potential biases and the difficulty of incorporating results in risk models. But the availability of universal ESG scores has created the opportunity for even small banks and individual investors to include assessments of resilience in their credit decisions.

Just as credit scoring revolutionized and democratized lending to consumers and small businesses, ESG scoring empowers lenders to assess organizational characteristics robustly and quantitatively. What’s more, we’ve only just scratched the surface of what proper ESG can accomplish, particularly when it’s used collaboratively.

Take, for example, the current supply-chain concerns. Interlinked company databases can be used to enhance ESG scores, with identification of not only a business’s suppliers but also the suppliers to those suppliers. Geographic and other vulnerabilities can therefore be identified in advance of approving a loan, rather than after the fact.

Risk management has always been a highly creative endeavor. We are constantly on the lookout for new data that can give us just a small edge in identifying risks and opportunities relative to our competitors.

While we may not be able to control the future when it comes to tail-risk shocks, we can control our reactions to these events. Understanding which organizations are best equipped to manage through adversity may be one of our single-best tools for managing uncertainty.

Cristian deRitis is the Deputy Chief Economist at Moody's Analytics. As the head of model research and development, he specializes in the analysis of current and future economic conditions, consumer credit markets and housing. Before joining Moody's Analytics, he worked for Fannie Mae. In addition to his published research, Cristian is named on two US patents for credit modeling techniques. He can be reached at cristian.deritis@moodys.com.