In a 2019 letter to their top federal regulators, executives representing Fifth Third Bancorp, PNC Financial Services Group, Regions Financial Corp. and other big regional banking companies warned that the transition from Libor to SOFR (the Secured Overnight Financing Rate) could adversely affect loan availability.

They reasoned that a risk-free rate (RFR) such as SOFR will fall during periods of economic stress, causing banks’ returns on SOFR-linked loans to drop just as their cost of funding increases. The “significant mismatch between bank assets (loans) and liabilities (borrowings)” would be exacerbated by commercial customers opportunistically hoarding liquidity by drawing down previously committed, low-cost credit lines.

A Federal Reserve Bank of New York staff report, published in December 2022 and revised in February, backs up and expands upon the banks’ claims about the effects of SOFR – an RFR without a credit-risk component – on balance sheets and the cost of future loans.

The paper, whose authors include Stanford Graduate School of Business professor and New York Fed resident scholar Darrell Duffie, says it is “the first to probe the implications of reference rate choice for incentives to provide credit, and the first to quantify the impacts of reference rate transition on credit provision based on detailed data on bank assets and liabilities.” The research found that the impact of the SOFR transition on credit supply “varies markedly across types of banks,” and that the large regionals are most affected.

Markets and Prices

The banks pointed out that “during times of economic stress, SOFR (unlike Libor) will likely decrease disproportionately relative to other market rates as investors seek the safe haven of U.S. Treasury securities . . . The natural consequence of these forces will either be a reduction in the willingness of lenders to provide credit in a SOFR-only environment, particularly during periods of economic stress, and/or an increase in credit pricing through the cycle.”

They suggested “a sensible and practical way to address these risks is to create a SOFR-based lending framework that includes a credit risk premium.”

“We find that in our calibrated model, corporate borrowers do borrow a lot more, at least 50% more, in a stressed period,” Duffie said in an interview.

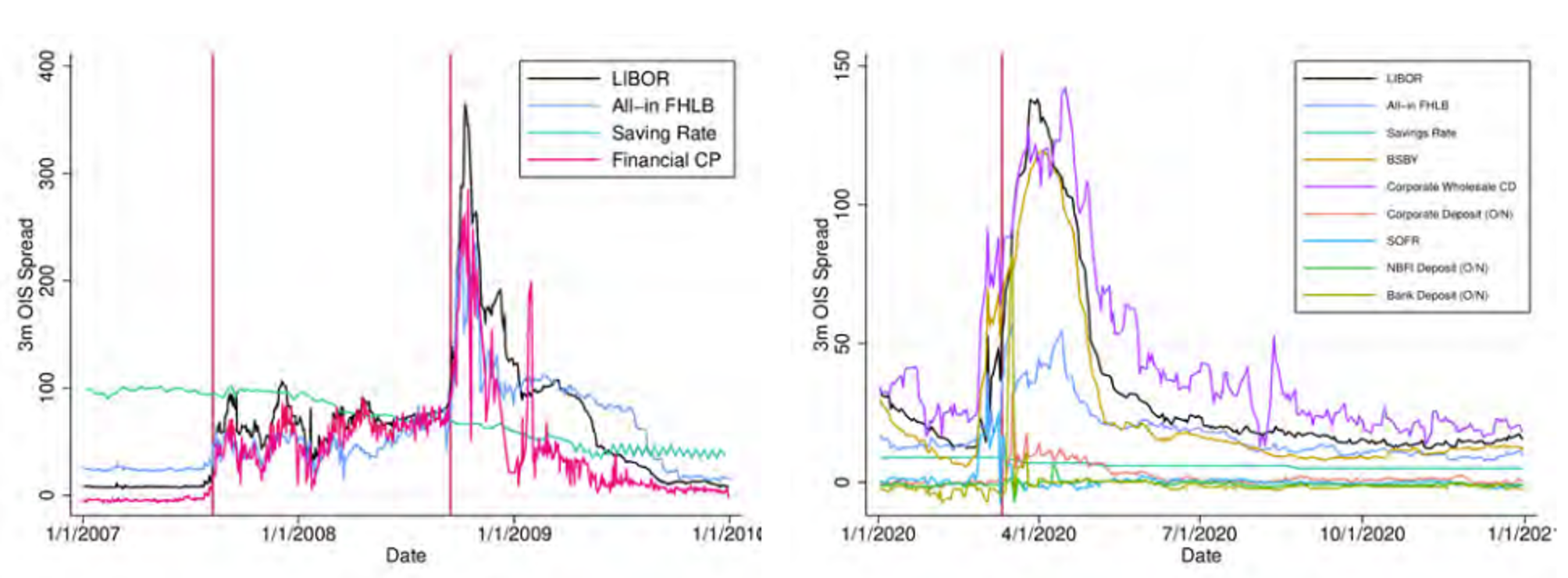

Bank funding rate patterns were similar during the Global Financial Crisis (left) and COVID-19 recession (right), though the Libor-OIS (overnight interest swap) peak in 2020 was lower. (Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Bank Funding Risk, Reference Rates, and Credit Supply, page 18)

The Fed report, in accordance with the regional banks, says that bankers are likely to price heightened risk into future loans, increasing the cost for borrowers who in turn may seek less credit. The report calibrates the expected cost of drawn credit to rise by 14 basis points, total credit-line commitments to fall by 3%, and the quantity of drawn credit to drop by 2%.

“Banks will bear in mind that in the next stress period, they may need even more funding, and some of that funding would be at expensive rates,” Duffie said.

Deposit Windfall?

An important mitigating factor during the pandemic, Duffie noted, was that corporate borrowers ended up depositing a significant portion of their credit-line drawdowns, which ended up “being a windfall for the banks instead of a big cost.”

However, the windfall was more significant for money-center banks than for regionals, and it’s unclear whether banks’ deposits would increase in future stress events to the same extent as during the pandemic. Duffie said the largest banks retained nearly all of their corporate customers’ drawdowns as deposits, while the regionals’ figure was closer to 40%. During the 2008 financial crisis, by contrast, corporates did not deposit their credit-line drawdowns, suggesting that this may be related to the nature of a given crisis.

Matthew Tyler, corporate treasurer of Zions Bancorp. in Utah, a signer of the 2019 letter, noted that during the pandemic, credit lines were drawn down significantly and stayed in the bank. “COVID wasn’t really a financial crisis for many of our customers,” he explained, “but rather a health crisis where borrowers were worried about what the financial impact could be.”

QE Effect

Jill Cetina, a Moody’s Investors Service associate managing director and former vice president for supervisory risk and surveillance at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, said the New York Fed paper doesn’t consider how the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing (QE) asset purchases during the pandemic impacted banking system deposits.

Jill Cetina of Moody’s

She said the biggest banks were able to fund the bulk of commercial-line drawdowns with higher deposits in part because most of the securities the Fed purchased in the secondary market were from nonbanks that don’t have accounts at the Fed. Consequently, the nonbanks had to keep those funds at a bank, thus creating reserves and deposits in the banking system, and especially at the largest banks that tend to service the nonbanks.

However, such a deposit surge may not occur in future stress periods, such as the recession that many economists have been anticipating.

“It’s fairly common in a recession for corporates to draw down their lines,” Cetina said. “But given the level of inflation today, I don’t know if the Fed would engage in QE. The banking system could perform differently depending on the nature of the stress situation.”

Additional Alternatives

Other replacement rates have emerged that are structured to reflect a degree of bank credit risk, including the American Financial Exchange’s Ameribor and the Bloomberg Short-Term Bank Yield Index (BSBY). Another in the works is the Invesco USD Across-the-Curve Credit Spread Indexes (AXI), which reflects credit risk that supplements SOFR and would widen during periods of stress.

Adoption of these benchmarks pales compared to SOFR, which is championed by the New York Fed-hosted Alternative Reference Rates Committee (ARRC) and strongly endorsed by regulators.

The New York Fed report estimates that during “normal times, SOFR-linked [credit] lines are about 25 basis points more expensive than Libor-linked lines.” The Libor alternatives incorporating credit risk should also be less expensive than SOFR. So far, though, banks do not appear to be pricing a wider spread over SOFR to mitigate its potential risks.

Allowing for Choice

“I don’t think spreads over SOFR have widened, and in fact they’ve actually come in a bit,” Tyler observed.

Zions offers a choice of loan pricing benchmarks. Tyler said the SOFR portfolio is bigger than Ameribor or BSBY, due in part to regulators promoting it. While the bank has suggested Ameribor and BSBY for loan syndications, other lenders have preferred SOFR.

Borrowers consider SOFR attractive, especially since they can obtain additional credit at lower rates when there is market stress, Tyler said. But borrowers holding loans priced over a credit-sensitive rate will see the rate go up. So even if banks were to add a credit-sensitive spread such as AXI to SOFR-based loans, making them less expensive than loans based solely on risk-free SOFR during benign conditions, borrowers may still choose to pay a premium to be protected in stress periods.

“We would welcome a credit-sensitive rate,” said the Zions treasurer. “The question is whether the borrower would welcome it.”

Topics: Financial Markets