There is no summer respite for risk managers at asset management firms as they work toward an August 19 deadline to comply with Securities and Exchange Commission Rule 18f-4, which requires them to defend the risk profiles of investment funds with more specificity than ever before.

The 400-page rule, in effect since February 2021, is designed in part to enhance transparency of funds holding derivatives. It breaks new ground by requiring fund managers to use Value at Risk (VaR) calculations to measure the dollar value of potential losses that their funds could incur at a 99% confidence level, with a time horizon of 20 trading days, and at least three years of historical market data. Companies must compare the risk of each fund under management to one of two reference portfolios: either an in-house fund that represents an appropriate risk benchmark, or an off-the-shelf index fund.

Internal debates are likely to ensue over how to meet the risk reporting requirements, such as which VaR models to use. Risk managers will have to generate numerous new reports and run new tests. In the process, they’ll have to make sure that investments that were previously not classified by the SEC as derivatives are correctly reported under the new rule – like short sales, in which securities are borrowed.

VaR Weaknesses

The months ahead pose significant challenges, as risk managers will have to align the realistic intent of each investment strategy with the SEC’s 20-day requirement. VaR tends to produce unacceptably risky outlooks for high yield bond portfolios that state pension funds own. Fund managers will also have to reconcile multiple asset classes in single portfolios, which most risk systems can’t track. Another issue is that simulations embedded in VaR models do not anticipate events like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Dan diBartolomeo, Northfield

As a result, VaR models can be “numerically wrong” and “conceptually wrong” for many types of investment portfolios, Dan diBartolomeo, president of Northfield Information Services, said in a March online workshop, Asset Manager Compliance with the SEC Rule 18f-4. As a result, compliance with many aspects of the rule can’t be completely fulfilled by vendor systems – assuming that those systems are up to speed. DiBartolomeo said that he hears from his clients that “a lot of organizations are not yet ready to fulfill them in a way that we think is analytically sound.”

Risk managers will have to explain to fund board members, not all of whom have backgrounds in accounting, that the new rule poses numerous riddles. One is which VaR model to use to calculate the risk of a fund – historical simulation, parametric, or Monte Carlo, for example.

“Using different methods will give you different answers. Is one of those right? Is one of those wrong? It’s open to interpretation perhaps,” Andrea Shaeffer, managing director for investment risk management at PPM America, which has $78.7 billion under management, said during a GARP Chicago Chapter webinar in May.

Once the fund’s board agrees on which VaR model to use – and use consistently across the firm’s entire fund complex – the next step is back testing. Risk managers will have to “be creative” enough to “come up with stress tests that might not result in a VaR breach but may not be appropriate in light of the fund’s investment strategy,” Shaeffer said.

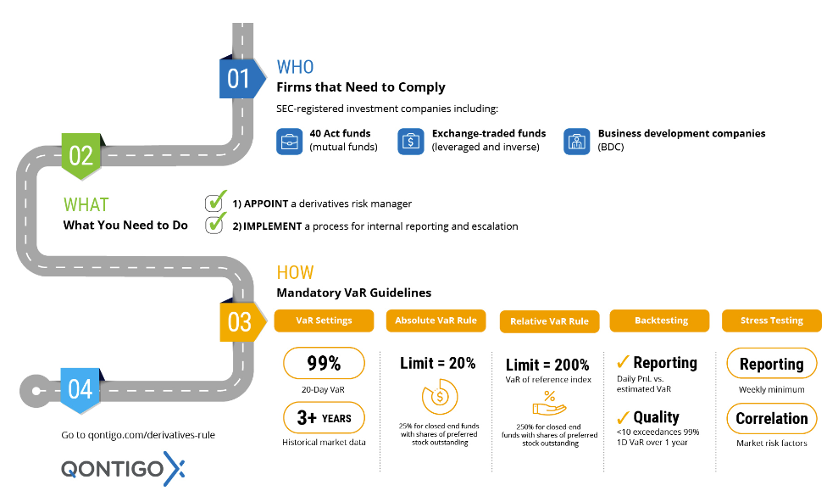

A Qontigo infographic illustrates “the road to compliance.”

Unshared Learning

Rule 18f-4 compliance would be easier but for a lack of shared insight. “One question I get asked is, ‘Do you have any best practices or examples for guidelines?’” Elizabeth Scalf, U.S. Bank Global Fund Services chief compliance officer, said in the GARP Chicago session. “Frankly, we don’t have that yet because most firms are still dealing with how to grapple with this and haven’t really been willing to share yet.”

Another riddle concerns the benchmarks for VaR comparisons. A convenient choice might be a securities portfolio that the company already manages in-house, though it would have to exclude any derivatives – even if the fund that it’s being compared with invests in derivatives, Michael McGrath, an asset management and investment fund partner at K&L Gates in Boston, said in the GARP meeting. If the company can find an exact match among published indexes – say, the Russell 1000 Index of large-cap stocks – then it may use that index’s VaR. The question some companies will wrestle with, according to McGrath, is, “When do we use one or the other?”

More questions revolve around the use of subadvisors, which are separate firms managing different parts, or “sleeves,” of mutual funds. Kenneth Fang, associate general counsel of the Investment Company Institute, told the GARP audience that ICI is fielding questions from fund managers about how they are expected to agree on VaR calculations with subadvisors. “I think VaR is difficult because it’s done on a portfolio level,” Fang said. “If you have multiple subadvisors that manage different sleeves, it’s hard to put a limit on risk.”

Derivatives Risk Manager

Many of these issues could be compounded for asset management companies that take advantage of an aspect of the new rule that explicitly allows mutual funds, exchange-traded funds and other funds governed by the Investment Company Act of 1940 to invest in derivatives. For instance, companies that make such investments are required to appoint a derivatives risk manager who reports directly to the fund’s board. Where no one has been thus designated, such as at smaller advisors, “the chief compliance officer is, unfortunately, stuck with this position,” U.S. Bank’s Scalf said.

To be sure, more education will be required at asset management firms. As with cybersecurity and other complicated risks, Scalf said, the CCO will “need to be able to talk intelligently” about VaR and “at least understand which model your firm is using.”

When board members start asking why the results of a parametric VaR calculation might be preferred over a historical simulation, or why the firm can’t use an in-house fund as a benchmark, the answers will have to be communicated clearly and repeatedly.

“As risk managers, we can be guilty of making things opaque,” said PPM America’s Shaeffer. “This is a time to make things clear. Most of us need to hear things multiple times before we can internalize them.”

Topics: Investment Management