Securities and Exchange Commission Chair Gary Gensler’s regulatory activism has set off debates between rival political factions, but on one matter they may find common cause: the slump in public stock offerings.

The numbers tell the story of a sputtering capital-formation engine and, conversely, of many companies preferring to stay private, thereby dodging regulatory costs and disclosure requirements while raising public policy questions and complicating the decision-making of investment-portfolio and risk managers.

Between 1997 and 2021, U.S. public companies declined to 4,071 from 7,414, Mayer Brown partner Anna T. Pinedo said in March 3 testimony to a House Financial Services subcommittee

That same day at Columbia University in New York, SEC Commissioner Mark T. Uyeda noted there were 4,194 initial public offerings by U.S. operating companies between 1990 and 2000 – almost double the 2,276 in the two decades through 2021.

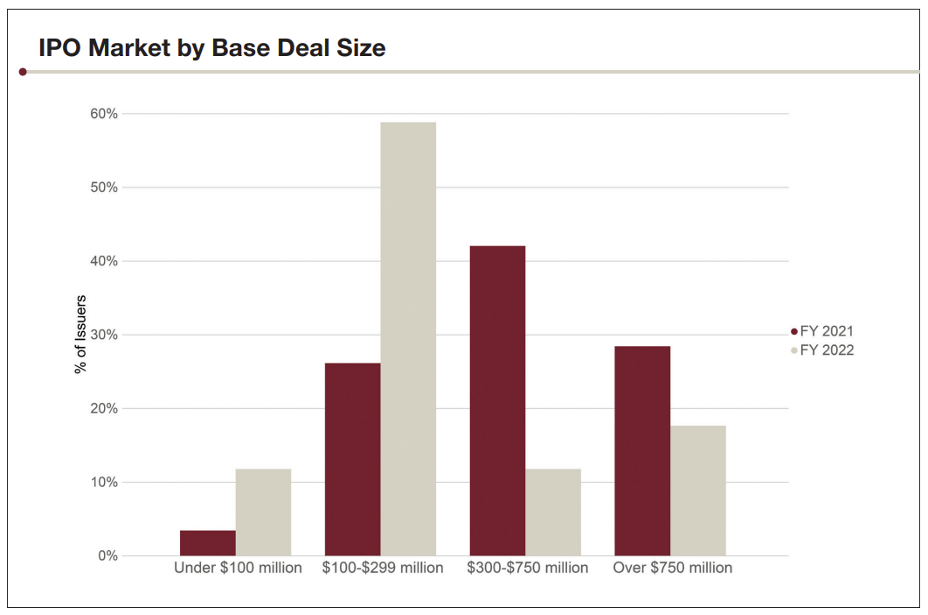

Source: Paul Hastings, Going Public: U.S. IPO Report

IPO volumes are falling globally – 70% this year through late March, with the U.S. seeing the steepest drop, according to Bloomberg. A review of U.S. IPOs from law firm Paul Hastings found that the amount raised plummeted to $9.5 billion in 2022 from more than $150 billion the year before. It anticipated continued softness in the market as “companies seeking to go public will continue to contend with the SEC’s proposed new rules and frenetic rulemaking pace.”

Policymakers and securities market observers agree that the causes are complicated and there are no silver bullet solutions. Uyeda, for one, contends the SEC “should create a regulatory environment that appropriately balances the costs and benefits associated with any required disclosures, while considering its investor protection mission. This starts by ensuring that the commission’s disclosure regime mandates information only if it is financially material.”

“This migration is serious and worthy of critical study, and it may very well increase with more regulation and litigation coming,” JPMorgan Chase & Co. Chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon wrote in his latest annual shareholder letter. “We really need to consider: Is this the outcome we want?”

On the Agenda

Two measures now wending their way toward an SEC rulemaking could be an indication of the agency’s ability to help move the needle back in favor of going public.

“I propose incremental reforms to Reg D,” as Commissioner Caroline A. Crenshaw put it in a January speech.

SEC Commissioner Caroline Crenshaw

The pending actions coming out of the Division of Corporation Finance are recorded on the SEC website: Regulation D and Form D Improvements addressing investor protections and the definition of accredited investor; and Revisions to the Definition of Securities Held of Record, amending the “held of record” definition to recalibrate how issuers count actual shareholders, which could require some large private firms to issue public securities.

The reforms have yet to be placed before the five-member commission to initiate a formal rulemaking, but Crenshaw is on record with her support.

Historical Roots

While the tilt toward private offerings is deep-seated in securities law and market dynamics, Crenshaw said it is since 1982 that “Rule 506 of Reg D and other exemptions under the Securities Act [of 1933] have changed the landscape of the private markets entirely . . . Whereas, in prior decades, small private issuers who grew and grew had to turn to the public markets to sate their capital needs, now Reg D, among other legal and regulatory mechanisms, has allowed for the development of pools of private capital sufficient to satisfy the needs of even the largest private issuers.”

Private issuance growing much faster than public, and companies waiting longer to launch IPOs if they do so at all, helps to explain how so-called unicorns, or private issuers valued at more than $1 billion, have skyrocketed to above 1,200, from 43 in 2013. An unintended consequence of Reg D may be that by drawing so much capital to unicorns, it hurts the small businesses it was supposed to help.

“Where we are today is a long way from where we began, when the federal securities laws first established true public markets with certain registration exceptions,” Crenshaw said.

Tailoring the Rules

“There should be more transparency to ensure a basic level of disclosure that allows investors, even the most sophisticated, to make informed investment decisions,” Crenshaw said. “And other regulatory obligations should be tailored for size.”

“Reforms to Form D can bring material information to investors, curing (at least to a degree) the informational asymmetry that is allowed currently,” the commissioner continued. “And second, we could import a two-tiered framework, similar to that under Regulation A (often referred to as mini-IPO offerings), which would impose certain heightened obligations on the larger private issuers and issuances . . . Different sizes of offerings would trigger different disclosure obligations.

“But unlike Reg A, additional obligations would be triggered by the size of the company, in terms of market cap, value or the size of the investor base. In other words, large private issuers – and not the small businesses at the heart of Reg D – would have additional obligations.”

When heightened obligations raise costs, “it certainly it makes the public option more appealing,” observed Itay Goldstein, finance department chair at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

Prior Advocacy

Crenshaw was preceded in her advocacy by Allison Herren Lee, who served on the SEC from 2019 to 2022 and in a 2021 speech said, “Even some of the largest and most widely traded issuers do not have enough record owners (as the term is currently defined) to meet the requirements of Section 12(g)” of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934. “As a result, the decision to file periodic reports has increasingly become optional.”

Allison Herren Lee

Two years before those remarks, in September 2019, a comment letter to the SEC from 15 law professors aired concerns about the risks associated with growth in private capital. They said “more aggressive” SEC action may be needed “to usher firms into the public markets.”

Among those who signed the letter were John Coffee Jr. of Columbia Law School; Saule T. Omarova of Cornell Law School, a future nominee to head the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency; and Erik F. Gerding, then of University of Colorado Law School, who joined the SEC Division of Corporation Finance in October 2019 as deputy director and became director in February 2023.

Beneficial Owner Reporting

Lee pointed out that over-the-counter market growth in the 1960s prompted Congress, on the SEC’s recommendation, to enact Section 12(g) to require issuers with 500 or more shareholders of record and, at the time, $1 million in assets to issue periodic reports. The agency proposed to include “known beneficial owners” – the underlying investors, as opposed to broker “street names” – in its proposed regulation, but that was not adopted in the final rule.

“While the commission did not ultimately exercise its authority at the time to require issuers to look through to beneficial owners, it is clear the commission has the authority to do so,” Lee said.

The 2012 JOBS Act raised the threshold of allowable accredited investors for remaining private but kept at 500 the number of non-accredited investors, which can include brokers and banks representing hundreds or thousands of beneficial owners. Lee said that public companies receive information about beneficial owners of their shares from the brokers and banks acting as shareholders of record.

“There is also evidence that private companies already have this information,” she said.

Other Accountabilities

“I’m not persuaded that we have a problem that we have to solve by forcing public disclosures by more of these companies,” said Carl Valenstein, a Morgan, Lewis & Bockius partner.

Carl Valenstein of Morgan Lewis

There remain justifications or incentives for staying private, he said, among them the Sarbanes-Oxley Act reforms that followed Enron Corp. and other scandals. They raised compliance costs and litigation risk, and going public today doesn’t bring the same bump up as before in terms of valuations and liquidity.

Regulatory agencies other than the SEC have jurisdiction over private companies, such as the Federal Trade Commission with its antitrust powers. “Theranos was brought down” by the Food and Drug Administration, “and then it was sued by investors,” Valenstein said.

“Companies choose to remain private for numerous reasons, many of which have little to do with commission policy,” the SEC’s Hester M. Peirce said in a March 2 statement at an Investor Advisory Committee meeting. “We should preserve companies’ ability to choose to stay private. But we must face the fact that as the commission piles rule upon rule, creating costs and liabilities that are not justified by the benefits, we play a central role in dampening any desire a private company may have to go public.”

“There are good reasons for such healthy private markets,” stated JPMorgan chief Dimon. They may include “public market factors such as onerous reporting requirements, higher litigation expenses, costly regulations, cookie-cutter board governance, less compensation flexibility, heightened public scrutiny and the relentless pressure of quarterly earnings.”

Topics: Financial Markets