The Black Swan casts a long shadow. The concept illuminated in Nassim Nicholas Taleb's book, required reading in investment and risk management and various other disciplines, seemed to explain so much about “the impact of the highly improbable,” as his subtitle put it.

It colored analyses and assumptions about catastrophes of rapid onset and devastating consequences, from the financial meltdown of 2008 - the year after The Black Swan was published - to the pandemic of 2020, and several crises in between.

It also stimulated deeper discussions about risk, uncertainty and predictability; about the value of scenario planning and the importance of agility and preparedness; and the hazards of herding and groupthink.

And, perhaps inevitably, there came revisionism: Not so much about black swans in theory, but rather how applicable and practical it is in addressing imminent and emergent risks that demand business and government attention and action.

In Taleb's formulation, a black swan is extremely low in probability and high in impact, and not fully explainable until after the fact - the opposite of “prospective predictability.” In retrospect, was the global financial crisis an “unknown unknown”? That event was preceded by risk assessments and warnings, largely unheeded, and the same could be said about the damage wrought by Hurricanes Katrina (2005) and Sandy (2012), the Deepwater Horizon oil spill (2010), the tsunami-driven Fukushima nuclear disaster (2011), the COVID-19 outbreak, and even the recent spate of cybersecurity breaches and ransomware attacks that caught corporations, government entities and critical infrastructures inadequately protected but not unawares.

Those are swans of a different color, and for some, the animal metaphor itself needs a new look.

Taleb edges into grey swan territory with a nod to Benoit Mandelbrot and “fractal randomness,” “allow[ing] us to account for a few black swans, but not all . . . A grey swan concerns modelable extreme events, a black swan is about unknown unknowns.”

“A lot of people have been mixing and matching grey, white, and black, with various combinations of animals, to try and get as lucky as Taleb,” quips Michael Mainelli, co-founder and executive chairman of London's Z/Yen Group. But such exercises can be helpful in confronting hard problems.

“I and others have used the term black elephant,” Mainelli says. That's “a cross between black swan - an unlikely, unexpected event with enormous ramifications - and elephant in the room - a looming disaster that is visible to everyone, yet no one wants to acknowledge.”

One currently getting a lot of acknowledgement is environmental: “We are all well aware of the main risks and challenges posed by climate change,” says the Bank for International Settlements, which co-sponsored the recent Green Swan 2021 conference.

Chicago-based strategist Michele Wucker founded Gray Rhino & Co. and titled her 2016 book The Grey Rhino. As with Taleb, Wucker's core message is in her subtitle: “How to Recognize and Act on the Obvious Dangers We Ignore.” She says that she did not seek to debunk The Black Swan so much as to raise awareness of threats “that are coming at us.”

“I've lost count of the crises for which warnings were plentiful but people have insisted on calling them black swans anyway,” Wucker wrote in a February blog on the “Texas deep freeze.”

Respecting the Grey

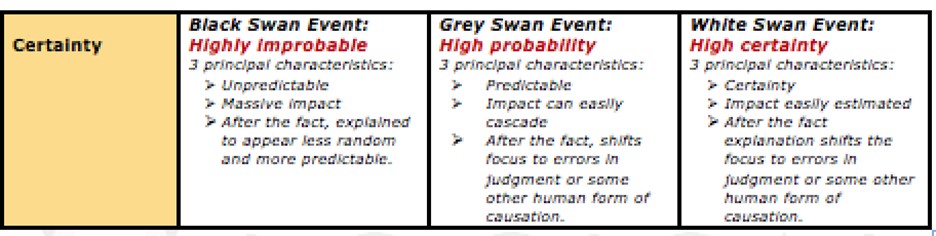

Black swans are “intrinsically unpredictable,” explains a report issued in April by risk services and solutions firm Aon. “Yet they have a huge impact (positive or negative) and can determine our futures.” World War I, as Taleb suggested, was a black swan event, improbably triggered by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand; World War II was not, because of the military mobilizations and unsettled geopolitics leading up to it.

The opposite, “white swan” events “occur with reasonable frequency, strike with reasonable impact, keep our data scientists busy and are inherently preventable,” says Aon. The title of its report, Respecting the Grey Swan, refers to those that “lie in wait and offer the most potential for improving our risk management strategies and making value-enhancing decisions.”

What falls short? Despite being warned of a grey swan, “[we] believe that it is unlikely to happen to us, and have invested our scarce resources elsewhere.”

The September 11, 2001 terrorist attack was grey, not black, because “the threat of a large-scale act of terrorism by al-Qaeda against the United States was well known,” Aon states. Likewise, several “epidemic and pandemic-prone diseases,” and a blunt warning from the World Health Organization in 2019 that “the world is not prepared,” preceded COVID-19.

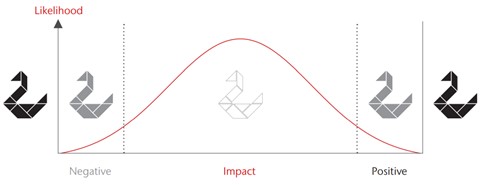

“White swans sit comfortably within normal expectations,” says Aon's Respecting the Grey Swan. “It is in the tails of the distribution, however, that we find the most fertile ground for insight.”

“We are aware of the possibility of these events, but, equally, understand their occurrence to be unlikely,” says the Aon report, a collaboration with Pentland Analytics and its founder, Dr. Deborah Pretty. They examine how cognitive biases, or “human frailties,” affect risk perceptions, and draw conclusions from a 40-year database of corporate reputational crises.

The result, Dr. Pretty writes, is “an evidence-based picture of the many challenges we face when seeking to manage extreme events, the magnitude of their impact, and the choices we can make in our ambitions for greater resilience and better performance.”

Governance failures or poor business practices such as executive malfeasance, allegations of discrimination and corruption, pricing or market manipulation and other misconduct accounted for 36% of the crises. Next most prevalent were product and service failures, 20%, and cyber attacks, 13%.

The stakes are significant: Over the 40 years studied, “the average impact on shareholder value is -8%, reflecting a total of $1.2 trillion in destroyed value.” The average value destruction in the governance category over the post-event year is nearly 15%.

An analysis of “minimum value impacts,” measuring the worst day in the post-event year for each of the reputation grey swans, concluded that “on average, were a reputation crisis to strike, shareholders can expect to lose 26% of value at some point” during that year, the study says. “This highlights the challenge that executives face with the sudden arrival of a grey swan event. In 36 of the 300 reputation crises studied, over 50% of value is destroyed.”

Identifying and Cataloguing

Taleb at one point calls the black swan “a great puzzle.” Asked to give examples in a Q&A on his publisher's website, Taleb says, “Most successful stories in the arts and letters are black swans. Outside the arts, my favorite one is the emergence of the computer and the internet. Also, almost all drug discoveries are black swans. The existence of the universe is a black swan.”

In The Black Swan - which followed a previous Taleb bestseller, Fooled by Randomness, and came before Antifragile, Skin in the Game and The Bed of Procrustes - he says the 1987 stock market crash may qualify as a true outlier - if viewed in a certain way, such as when lacking knowledge that the market can crash.

Such reasoning may or may not be useful to people in C-suites or on the frontlines who are charged with mapping and tracking the critical and tangible concerns that dot their risk landscapes, which are not populated by black swans.

“The only real macro black swan is if a gigantic meteorite hits the Earth, but there is nothing we can do about it. For almost everything else there are warning signs,” says Alla Gil, co-founder and CEO of advisory firm Straterix. GARP Risk Intelligence's FRM Corner columnist, Gil wrote in March and April about a comprehensive multi-scenario approach to tail risk “to discover early warning signals of an approaching adverse market environment - and to design mitigating contingent management actions that eliminate or reduce the risk.”

For a comprehensive take on clear and present dangers, the World Economic Forum's Global Risks Reports are annual benchmarks. The 2021 edition in January ranked 35 risks according to likelihood and impact. Infectious disease, No. 1 in impact, has been on WEF lists since 2006, evidence of their grey swan nature.

The latest report took a stab at “potential shocks that are less well known but would have huge impacts if manifested,” identified by a newly formed Global Future Council on Frontier Risks, of which Gray Rhino & Co.'s Michele Wucker is a member. Among these outliers: accidental war, collapse of an established democracy, and a gene-editing “arms race between geopolitical rivals with undetermined ethical consequences.”

Meanwhile, Wucker, whose new book is You Are What You Risk, is one of a host of experts - Control Risks, Eurasia Group and Stratfor are examples of other firms - who publicly release top-risk lists and forecasts. Wucker's top gray rhinos of 2020 and “peek ahead at 2021” was led by economic and financial fragilities, political and geopolitical uncertainty, and climate change, accompanying a reminder of “the urgency of dealing with the gray rhinos charging at us.”

At the end of last year, S&P Global Market Intelligence reported on advice from Macro Hive that investment strategists preoccupied with the pandemic should not avert their gaze from such grey swans as “a surge in inflation, negative Treasury yields, globalization of carbon taxes, military escalation between China and the U.S. over Taiwan, and even the discovery of intelligent life outside our solar system. Proof of aliens would cause tech and defense stocks to skyrocket and the spread between government and high-tech bonds to blow out.”

Legal & General Investment Management head of asset allocation Emiel van den Heiligenberg's grey swans coming into 2021 included: the Hong Kong dollar breaks its peg against the U.S. dollar; a central bank digital currency goes mainstream, cratering bitcoin; new medicines or vaccines will be developed for existing illnesses as a result of COVID-19 research, possibly including a cure for the common cold and major progress against cancer; and 2021 is the warmest year on record.

To the last he appended: “This unfortunately wouldn't really be a grey swan as the last five years have been the warmest five on record.”

Uncertainty, Unknowns and Accidents

The availability of information on any risks, up to and including unknown unknowns, harkens back to Risk, Uncertainty and Profit (1921) by University of Chicago economist Frank Knight. As The Black Swan boils it down, the distinction is between “Knightian uncertainty (incomputable} and Knightian risk (computable).”

Roulette, blackjack and lotteries “are examples of Knightian risk,” MIT finance professor Andrew W. Lo writes in Adaptive Markets (2017). “Finding intelligent life outside our solar system, exploiting fusion as a new source of energy, or surviving a nuclear war with Russia are examples of Knightian uncertainty.”

Knightian uncertainty, says Lo, occurs in industries using new, unproven and uncommoditized technologies whose “randomness can't be quantified. These unknown unknowns make most of us withdraw from the game. But these are also the circumstances in which billionaires are made . . . Human nature simply doesn't allow us to view uncertainty with indifference. Fortune favors the brave, and market prices reflect our innate tendency to avoid uncertainty.”

Z/Yen's Professor Mainelli took a different tack in a 2015 paper on uncertainty at the frontiers of finance and a talk titled Knightian Ignorance: Are You Not Thinking What I'm Not Thinking? Today, he ponders the quadrants formed by combinations of known and unknown (KK, KU, UK, UU), representing animals in different shades, but even that may have limited utility.

“I think people struggle with moving from fixed odds to a distribution function,” Mainelli says in an email. “If you take everything as a distribution function, then you're merely describing it with all these animal phrases. Basically, a 'tight' function for probability is 'normal', while one spread way down the long tail is not 'normal'. Same with impact.”

As the World Economic Forum compilations demonstrate, “pandemics were appropriately classified,” Mainelli says. “However, they were then ignored by the people in a position to do something about it. From this one might conclude that it's not the analysis that is the problem, it's assigning responsibility and appropriate resources against a backdrop of many competing and slippery assessments, but with finite resources for risk mitigation or reduction.”

Normal Accidents, as posited in Charles Perrow's 1984 book, may be an elephant in the room. “Perrow argued persuasively that the twin conditions of complexity and tight coupling were recipes for disaster in a variety of industry contexts,” Andrew Lo says. Complexity and tight coupling “explain not only why oil spills, airplane crashes, nuclear meltdowns and chemical plant explosions occur, but also why we should expect them to occur regularly.”

(For a current normal-accidents case study, see Years of Unheeded Warnings. Then the Subway Crash Mexico City Had Feared in the New York Times.)

As does Richard Bookstaber in A Demon of Our Own Design (2007), Lo finds Normal Accidents instructive regarding the complex and tightly coupled financial system and its recurring crises. Perrow, however, contended that these were more attributable to human conduct than to system complexity, and Lo concedes “he has a point.”

“But,” Lo counters, “isn't the source of all accidents, normal and otherwise, human behavior?”

Practical Matters

People in and close to the risk management function appreciate intellectual challenge and inquiry. But it has to be carried over into practice and results.

To longtime risk practitioner David Rowe, president of David M. Rowe Risk Advisory and author of An Insider's Guide to Risk Management, the too-easily-ignored grey swans “are far more common and collectively present a greater threat than genuine black swans. The good news is that we can at least apply some structural thought to these situations and potentially define some leading indicators to watch, which may indicate a rising likelihood of them being realized. We also can do some what-if analysis as to how to react, should they occur.”

In the same vein, Cara Williams, Risk Management and Regulatory Compliance practice leader with Spinnaker Consulting Group and author of the white paper Turning a Solid Risk Management Framework into a Competitive Advantage, says, “It will always be smart to try to plan for the unknown (like factoring for various scenarios in your business resiliency planning) and to have key, early warning indicators (like KRIs - key risk indicators) in place to get early warning of an upcoming event.”

Nick Sanna, president of FAIR Institute (Factor Analysis of Information Risk) - which hosted a presentation by Michele Wucker at its 2020 conference - says, “The gray rhino concept can have direct application in the risk identification phase,” helping to ascertain the frequency and impact of large risks. “Good risk management processes start with understanding the context in which an organization operates and identifying what risk scenarios might be most relevant in that context,” says Sanna, who is also president and CEO of RiskLens.

He adds: “The gray rhino concept has to be supported by formal, explicit risk identification and assessment processes to unleash its value, otherwise it can become a nice conceptual exercise.”

John Bree, a veteran bank risk executive who is currently chief evangelist and chief risk officer of Supply Wisdom, underscores the need for flexibility, agility and readiness amid disruption and uncertainty - and for recognizing the limitations of models and of certain human tendencies. He urges risk managers to widen their “apertures” and get out of their comfort zones to bring a necessary, holistic broadmindedness to bear.

Risk awareness, informed by an integrated view of risks, “is incredibly important and is a function of the type of event that may have occurred at an earlier time (e.g., South Korean MERS epidemic of 2015), and also what I refer to as risk sensitivity,” says Clifford Rossi, principal of Chesapeake Risk Advisors and professor-of-the-practice and executive-in-residence at the University of Maryland's Robert H. Smith School of Business. “Risk sensitivity is in turn dependent upon a set of management cognitive biases and the level of risk aversion of management - the point being that management teams that exhibit greater degrees of risk aversion and less bias (e.g., herd mentality, recency bias, etc.) wind up being more sensitive to risk events and risk-taking than other managers, which heightens their risk awareness to uncertain events.

“We still tend to be far more siloed in assessing risk than we should be,” Rossi continues, “and as we learned from the global financial crisis, we often find risks collide with one another. For example, subprime mortgage credit losses contributed to a liquidity crisis and to massive reputation risk, legal, regulatory and market risks during that period.”

Supervision and Market Incentives

Effectiveness at the practical level, Straterix CEO Alla Gil says, depends on a rigorous scenario methodology “to adequately capture the full range of outcomes with company-specific probabilities.” Also needed are risk managers' transparency in explaining their reasoning to boards, regulators and other stakeholders, as well as incentives that might start with supervision.

Just as “supervisors can punish organization for failing a stress test or audit,” Gil suggests, “they should require everyone to disclose their black swan, grey swan and gray rhino scenarios and explain what they do about them and why.” But because “supervision is a slow-moving mechanism” without readily available tools for verification and challenge, the “incentive push” could come first from markets, investors and rating agencies.

“The job of risk management is to be ready for any feasible combination of such shocks and their consequences,” Gil asserts. “However, from a risk management perspective, in my opinion, it doesn't matter what you call these events to distinguish between the known and unknown, size, etc. Instead, what I'm most focused on right now is working with organizations to build out a holistic risk management framework, and several other related building blocks, that will ultimately help them be able to more quickly and nimbly adapt so that they can run into the storm when it comes - thus shortening the impact - whether you know about it ahead of time or not.”

Cyber threats are a known, yet at the same time emerging and mutating. Risk educator and former CRO David X Martin, in his recently published CyRM: Mastering the Management of Cybersecurity, writes that “emerging technologies often create new risks that haven't been encountered before and that also add complexity to existing risks. The interconnected nature of these risks creates a need to deal with the risks concurrently, rather than in isolation. For example, the increased reliance on interconnected systems by companies will amplify the impact of failure and threaten resilience. Taking this a step further with artificial intelligence, there are reputational, legal and regulatory consequences as a result of algorithms that aren't totally aligned with social, ethical, cultural or legal norms.”

“If the past year has taught us anything,” Jen Easterly said in her June 10 confirmation hearing to become head of the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, “it's the obligation we have as leaders to anticipate the unimaginable.”