Even Silicon Valley has to face the music. Risk and regulatory pressures are rising for corporations everywhere, so it's not surprising to see some of the biggest names in tech taking steps to be ready for the onslaught.

Facebook hired its first chief compliance officer in January, and Twitter made a CCO appointment last May. But it was Alphabet, Google's parent, whose choice of compliance chief, in particular, made risk management professionals sit up and take notice.

Facebook and Twitter turned to lawyers: respectively, ViacomCBS CCO Henry Moniz, and in-house legal team member Marianne Fogarty. Google's selection, by contrast, was Spyro Karetsos, a seasoned financial services industry risk manager.

Succeeding Andy Hinton, a former prosecutor who left last March after more than 13 years in the job, Karetsos may be the closest thing to a chief risk officer Google - and most if not all of Big Tech, for that matter - has ever had.

Karetsos joined Google in October from TD Ameritrade, where he was CRO. (TD Ameritrade was acquired that same month by Charles Schwab Corp.) He also held high-profile risk positions at SunTrust Banks (now Truist Financial Corp.), Vanguard Group, Goldman Sachs, and the Federal Reserve Banks of Philadelphia and New York.

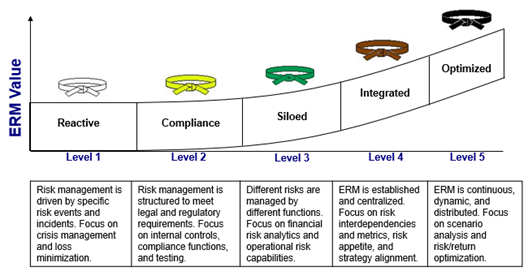

Appointing “an accomplished CRO with substantial enterprise risk management experience” was a “notable event” and “significant for the technology sector,” commented veteran risk manager and consultant James Lam. “That skill set is critical for fast-growing and large technology companies as they migrate from a reactive and compliance-oriented approach to more of an integrated and distributed model.”

Karetsos admitted that while at TD Ameritrade, he enjoyed being at a company that “pursues innovation by leveraging technology.” The same goes for Google, he shared, with that feeling “multiplied several times over.”

Google doesn't have a “traditional financial services command-and-control culture,” he said, adding, “The mission of the organization drives innovation and capabilities. Innovation is everything.”

Innovation, indeed, is the name of the game in Silicon Valley. It's risky business from the get-go. But robust enterprise risk management - the kind required in regulated industries like banking and brokerage - isn't a given. Not yet, at least, which begs the question: When is the right time to get down to business - the business of risk management, that is?

And what does - or should - risk management Silicon Valley-style even look like?

Risk Doesn't Come First

Early-stage or start-up ventures are mainly focused on “innovation and growth” and “don't build up the muscle memory for risk management and compliance,” noted Lam, a former CRO at GE Capital Markets Services and Fidelity Investments, and former chair of the board risk committee of E*TRADE, which Morgan Stanley acquired in October.

“Start-ups should integrate risk management and compliance practices into their culture, business processes, technologies (AI, data analytics) and business decision-making as they grow,” said the head of James Lam & Associates, based in the Boston area. “Once they get to [be] mid- to large-size, it becomes much more difficult, costly, and time consuming to retrofit those practices.”

This includes the boards of directors, Lam indicated, who are mostly “investors who also focus on innovation and growth” and where there are “no or few independent directors until they go public.”

Consultant James Lam believes most start-ups and high-tech companies are at Levels 1 and 2 on his Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) Program Maturity Model. Some are at Level 3 for certain risks like IT and cybersecurity. They need to move toward Level 5 as they scale, where risk management becomes a competitive advantage.

Silicon Valley start-ups are celebrated for leveraging technology, for being disruptors and doing business differently; for cutting-edge cultures unlike most in mainstream corporate America; and for being led by founders who, by virtue of being seen as visionaries and guided and financed by venture capitalists, are given free rein to play by their own set of rules. Facebook founder, chairman and chief executive Mark Zuckerberg's famous mantra, “Move fast and break things,” pretty well sums it up.

Reputations on the Line

As the organizations grow, risks become more complex and get compounded, putting corporate reputations on the line. Silicon Valley start-ups can find themselves in a Catch-22 as they scale, criticized for the very thing that made them special in the first place: the way they do business.

Companies like Google, Facebook and Twitter, having become iconic household names, are increasingly in the hot seat, under fire from within their own ranks as well as from governments, regulators, investors, and even the public and the media demanding accountability. They face allegations of monopolistic and predatory business practices, disrespecting data privacy, distributing disinformation, and censorship on social media platforms, among other things.

“I believe the so-called Big Tech companies have exposed themselves to enormous strategic, business, political and regulatory [e.g., Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act] risk in the seemingly arbitrary and capricious policies that they have implemented regarding use of these platforms,” contended Clifford Rossi, a former CRO of Citigroup's consumer lending division, now principal of Chesapeake Risk Advisors and professor-of-the-practice and executive-in-residence at the University of Maryland's Robert H. Smith School of Business. (Section 230 protects online platform providers from liability for third-party content.)

Rossi reasons that “each company's success has ironically led to an existential risk to the anticompetitive market power they currently wield.”

Legal Heat

In October, the U.S. Department of Justice and 11 states sued Google, alleging anticompetitive and monopolistic practices pertaining to its search businesses - the company's crown jewels, or what the complaint called the “cornerstones of its empire.” Google senior vice president, global affairs Kent Walker called the lawsuit “deeply flawed” on a company blog.

Google is also in the European Union's antitrust crosshairs: The European Commission has reportedly levied nearly $9.5 billion in fines over the past few years in three cases alleging unfair search dominance and product and market advantages. Appeals and challenges are pending.

Speaking generally about risk and compliance practices, CCO Karetsos, who reports to Walker, explained, “While we are required to adhere to existing laws such as privacy, consumer protection, IP, etc., innovation typically comes ahead of regulation, and regulation ultimately catches up.”

“As tech companies have gotten bigger, we're seeing greater attention from the regulatory perspective,” he said.

“The fully detailed rule set is not out there yet,” he added. “It's just starting.”

Karetsos believes it is “more effective and more efficient” to “get more front-footing and work with global regulators.”

“You don't have to wait to implement what good looks like in the risk and compliance space,” he advises.

Size and Power

The Big Techs make for big targets. Alphabet hit $1 trillion in market capitalization for the first time in January 2020.

Google dominates the global search engine business with, according to various estimates, around a 90% market share. Its YouTube affiliate disclosed it has over 2 billion users worldwide amounting to “almost one-third of the internet.”

Facebook reported 1.84 billion daily active users on average for December 2020, and the numbers bandied about for Twitter usage are around 500 million tweets sent per day, approaching 200 billion per year.

All three social media giants took actions against then-President Donald Trump following the January 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. Twitter permanently banned him, with co-founder and CEO Jack Dorsey tweeting it was the “right decision” while expressing reservations. Facebook blocked Trump indefinitely from both Facebook and Instagram and reportedly turned the matter over to an independent Oversight Board it established last year to make the final decision, and Google suspended his YouTube account indefinitely.

“At this point their policies regarding use of their platforms seem much more like a visceral reaction to current events in terms of some of the actions being taken for whatever strategic objectives they may have, rather than a methodical exercise in risk management,” Rossi observed.

A Call for Oversight

In a 2018 shareholder proposal, Trillium Asset Management chief advocacy officer Jonas Kron similarly singled out Facebook: “The sheer volume, magnitude, and frequency of Facebook's controversies strongly suggest that the company's whack-a-mole approach is insufficient.”

“Facebook needs to institutionalize stronger risk oversight mechanisms,” he argued.

Trillium prodded Facebook's board to consider the merits of a stand-alone risk oversight committee. The proposal passed, but the board absorbed risk into its Audit Committee, now the Audit and Risk Oversight Committee. Kron said in an interview that it was a step in the right direction but didn't go far enough.

The following year, Trillium and other investors advocated separating the roles of CEO and chair, the latter being an independent director who could “focus on oversight and strategic guidance,” according to the shareholder filing. Kron recalled it “ran into a lot of resistance” and was voted down, although it received strong support from outside shareholders. Zuckerberg holds both titles and essentially has voting control of the company due to a dual-class stock structure. Five Facebook independent board members have left in the last couple of years, reportedly due to differences around governance, among other things.

Marianne Jennings, a professor at the W.P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University and author of The Seven Signs of Ethical Collapse: How to Spot Moral Meltdowns in Companies . . . Before It's Too Late, cautions that strong governance controls are necessary to keep charismatic and controlling leaders in check and, in a worst-case scenario, to prevent them from taking their companies down with them.

“A strong board can solve a lot of issues with an insular CEO,” Jennings maintains. If the board is weak, “there's nowhere for an external auditor or employees to turn.”

Financial Industry as Benchmark

Looking ahead, Rossi said it would be “wise” for these Silicon Valley companies to “put some guardrails in place to ensure they can establish their risk appetite and manage their risks accordingly.”

Lam recommended: “High-growth technology companies should benchmark the ERM and compliance practices at large financial institutions and adopt and customize these practices.” That includes putting a CRO, dedicated risk committee of the board and strong ERM in place.

He pointed out that after the post-financial-crisis Dodd-Frank Act kicked in, risk and compliance costs of the biggest banks reached 12% to 15% of their operating expenses at the peak. “That's not sustainable for any company,” Lam warned. “But it's what's ahead of the Big Tech companies if they do not do the right things.”

L.A. Winokur is a veteran business journalist based in the San Francisco Bay Area.