What went wrong?

The question was unavoidable from the moment in March when Silicon Valley Bank went down. It only grew more insistent with the subsequent failures of Signature Bank and First Republic Bank amid what policymakers feared could devolve into a crisis of systemic proportions.

By the end of April, there were reams of explanation and documentation: The Federal Reserve Board and Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. had delivered detailed reports on SVB and Signature. The Government Accountability Office and California and New York state regulators also weighed in. The findings were aired in congressional hearings where senior regulators faced pointed and at times hostile questioning.

As recently as June 1, Agustín Carstens launched into “what went wrong” in a European Banking Federation summit speech in Brussels. Carstens, who is general manager of the Bank for International Settlements and well networked with global central bankers and regulators, arrived at some answers while also commenting on the prevailing dialogue.

“Many have pointed fingers at rapid interest rate hikes, falling bond prices and flighty depositors. In some cases, these provided the trigger,” Carstens observed. “But in my view, the main cause of recent bank crises was the failure of directors and senior managers to fulfill their responsibilities. Business models were poor, risk management procedures woefully inadequate and governance lacking.

BIS’s Agustín Carstens: “Supervision needs to up its game.”

“These issues existed well before depositors ran and investors lost confidence,” the BIS chief went on. “Many of the shortcomings could, and in my view should, have been identified and remedied ahead of time. This speaks to the crucial role of banking supervision.”

Indeed, board and executive-level oversight, regulators’ supervisory processes, and the social-media-accelerated deposit runs are widely accepted as primary causes. How these perfect-storm contributors interrelated, and how much weight to attach to each, has been open to discussion.

Scrutinizing Supervision

While seeing “the ultimate cause” of the bank failures in “the institutions themselves,” rather than regulators or rising interest rates, Carstens came down strongly on how “banking supervision needs to up its game. It needs to identify weaknesses at an early stage and act forcefully to ensure that banks address them.

“To do this, supervisors will need to have operational independence, strengthen their forward-looking culture and adopt a more intrusive stance. They will also need to continuously seek to improve their capabilities. First, by accessing greater resources. And second, by enhancing their productivity with the aid of technology.”

Centering on the supervisory shortfalls, the Government Accountability Office’s April preliminary review noted that both SVB and Signature Bank “were slow to mitigate the problems the regulators identified [dating back to 2018], and regulators did not escalate supervisory actions in time to prevent the failures.”

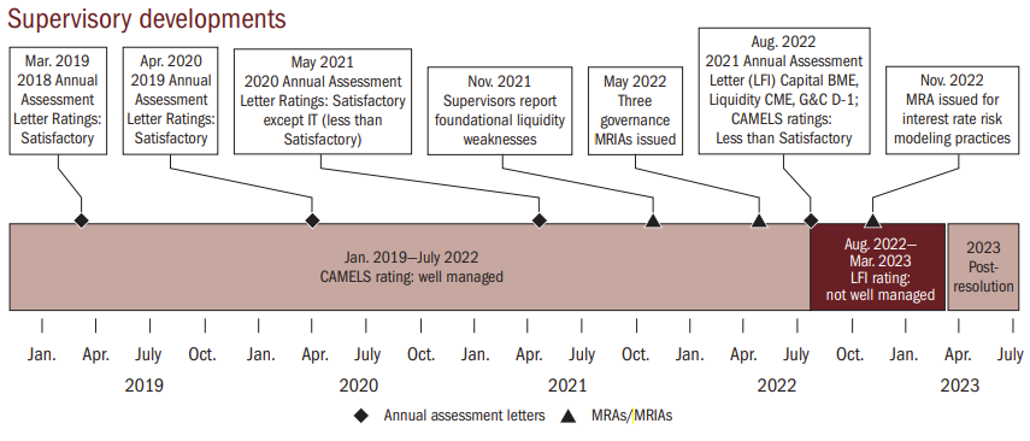

A timeline from the Fed’s Review of Regulation and Supervision of Silicon Valley Bank.

A timeline from the Fed’s Review of Regulation and Supervision of Silicon Valley Bank.

The GAO found that after having rated SVB as satisfactory, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF) downgraded it in June 2022 “and began working on an enforcement action in August 2022. However, it did not finalize the action before the bank failed.” The FDIC “took multiple actions to address supervisory concerns related to Signature Bank’s liquidity and management, but did not substantially downgrade the bank until the day before it failed.”

Conceding that it likely had not yet captured the complete picture, the GAO said, “We plan to further examine FRBSF and FDIC supervisory decision-making and other related issues in an upcoming GAO review.”

Regulators Under Fire

The GAO, which is an arm of Congress, is not alone in seeing a need for further study. For all the fact-finding and general consensus, questions have been raised about the comprehensiveness of the reports from the regulators, and whether their self-examinations should suffice as the definitive word.

Representative Patrick McHenry, chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, set a prosecutorial tone from the start.

“We know [Silicon Valley Bank] was mismanaged, that much is clear,” the North Carolina Republican asserted in opening a March 29 hearing that put Michael Barr, the Federal Reserve’s vice chair for supervision, who spearheaded the central bank’s internal review, on the hot seat. “Now we need insight into the decisions and decision-making process of financial regulators related to the second- and third-largest U.S. bank failures.”

Congressman Patrick McHenry: “Now we need insight.”

To Barr, McHenry said, “This committee would like to understand your thinking in the key hours of that first week in March. Was there adequate planning for a large-scale bank run? Did the chief supervisor follow the playbook to ensure the bank did not fail? How did the chief supervisor and examiners miss the hole in the bank’s balance sheet?

“Additionally, the committee has no insight into the decision-making or the actions by the FDIC chair on Friday the 10th through that Sunday evening when the systemic risk exception was announced,” McHenry continued, referring to FDIC head Martin Gruenberg, the March 12 closing of New York’s Signature Bank, and the extension of deposit insurance coverage beyond the $250,000 per-account-holder limit.

“Again, did the FDIC chair use all the tools at his disposal to resolve the banks that weekend?”

Admitted Weaknesses

Barr characterized the Fed’s SVB self-assessment, released on April 28, as “an unflinching look at the conditions that led to the bank’s failure, including the role of Federal Reserve supervision and regulation.”

Barr’s “key takeaways” included the bank’s risk management failings – the “textbook case of mismanagement” of which he previously spoke – and supervisors’ not effectively ensuring that the bank fixed problems that had been identified.

The Fed’s overall surveillance and analytics were “largely fit for purpose,” according to the report. Issues “most relevant” to SVB’s failure – rising interest rates, impact on securities valuation, and liquidity pressure – “were identified, analyzed and escalated.” However, it added: “The reviews did not consider the potential for extreme tail events like a rapid outflow of deposits or the systemic implications of broad runs on uninsured deposits. It is unclear how these assessments actually informed the supervisory process or outcomes.”

Some unknowns were also acknowledged in a “matters for further study” section of the FDIC’s report on Signature Bank. First on the list: Reiterate the Division of Risk Management Supervision’s “forward-looking supervision philosophy and the importance of addressing risk management weaknesses before financial decline occurs.”

Also cited was a need to evaluate enforcement and escalation processes “when bank management is unable or unwilling to effectively address chronic problem areas.”

“More to Learn”

Such evaluations have served a purpose, but they raise questions of objectivity, and “there is more to learn,” says Peter Conti-Brown of the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

At a May 17 hearing of the Senate Banking Committee’s economic policy subcommittee, Conti-Brown said the Fed did well to disclose excerpts from SVB examination reports that are usually confidential, and its conclusions “in some respects make good sense.

“But in my view, the investigation should never have occurred in public,” added Conti-Brown, who is Class of 1965 Associate Professor of Financial Regulation and co-director of the Wharton Initiative on Financial Policy and Regulation. “The Federal Reserve and the extraordinary public servants who work therein are good at many things. They are not good at self-investigation for purposes of public accountability. Nor should we expect them to be so . . . The Fed cannot supervise itself. That is Congress’s job.”

Fed Governor Michelle Bowman: Internal reports were first step.

Hence, Federal Reserve Governor Michelle Bowman, among others, has called for additional, independent investigations.

The “preliminary and expedited internal reports . . . are an important first step for the U.S. bank regulators working to identify root causes of these bank failures and holding themselves accountable for supervisory mistakes,” Bowman said in May. But, she added, “I believe that the Federal Reserve should engage an independent third party to prepare a report to supplement the limited internal review to fully understand the failure of SVB. This would be a logical next step in holding ourselves accountable and would help to eliminate the doubts that may naturally accompany any self-assessment prepared and reviewed by a single member of the Board of Governors.”

Widening the Scope

Bowman suggested that the external report “cover a broader time period, including the events of the weekend following the failure of SVB, and a broader range of topics beyond just the regulatory and supervisory framework that applied to SVB, including operational issues, if any, with discount window lending, Fedwire services, and with the transfer of collateral from the Federal Home Loan Banks.”

Also last month, Senate Banking Committee members Jon Tester, Democrat of Montana, and Thom Tillis, Republican of North Carolina, requested in a letter to President Joe Biden the appointment of an independent investigator. An examination covering “the full jurisdictional scope of these failures, led by non-partisan experts, is critically important,” they wrote, whereas the regulators’ “self-reflection, while appreciated, is insufficient to ensure stressors to our financial system of this magnitude are not repeated . . . An outside, independent review of the supervisory and management errors that contributed to the failures would be a vital step toward restoring confidence in the banking system and preventing future failures.”

Senator Elizabeth Warren, a Massachusetts Democrat and banking committee member, is seeking reforms in the Federal Reserve’s own governance, ethics and disclosures through a proposed Strengthening Federal Reserve System Accountability Act, introduced with Florida Republican Senator Rick Scott. Warren is pushing for the agency’s inspector general, who currently is appointed by, and subject to removal by, the Federal Reserve Board chair, to be presidentially-appointed and Senate-confirmed.

Wharton’s Conti-Brown agreed, at the subcommittee hearing which Warren chaired, that “we need better accountability than this system provides.” He believes the Fed and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau should be separated for oversight purposes; the Fed inspector general’s purview should include the regional reserve banks as well as the Board of Governors; and the IG “should be a separate presidential appointment, confirmed by the Senate.”

Supervisory Specifics

Conti-Brown offered a contrarian, more positive critique of bank supervision during a June 14 Peterson Institute for International Economics webinar. Inferring from the SVB documentation that many banks were concurrently shown balance-sheet “red flags” in their examinations, the professor said the supervisors are due some credit for the vast majority of institutions’ awareness of, and effective responses to, the brewing risks.

Before the economic policy subcommittee, risk consultant and educator Mayra Rodríguez Valladares, managing principal of MRV Associates, supported both presidential nomination of the Federal Reserve inspector general and an independent investigation of the SVB failure.

For the latter, Rodríguez Valladares compiled several sets of questions delving into supervisory orders, the bank’s responses and subsequent follow-up. Among those, as posed in her testimony:

-- After repeated MRAs (matters requiring attention) and MRIAs (matters requiring immediate attention), where is there documentation showing any SVB remediation plans?

-- How many regulators knew about SVB’s numerous audit, compliance, and risk identification and measurement shortcomings and failures? Did they have a responsibility to notify the Financial Stability Oversight Council about SVB’s problems?

-- What documents exist that detail the exact relationship between the Board of Governors and Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco in all matters pertaining to SVB?

-- What is the exact supervisory process at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco? If any examiner was dissatisfied that matters were not being escalated to the level of enforcement, what recourse did they have?

-- Where is SVB’s internal audit documentation of the bank’s challenges as well as external auditor KPMG’s documentation? Both could shed light into the extent of SVB problems. Did either set of auditors liaise with Fed and California regulators at any point?

Mayra Rodríguez Valladares: “Tone at the top of bank supervision is critical.”

“The Federal Reserve has guidance for how examiners communicate findings to supervised banks,” namely MRAs and MRIAs, Rodríguez Valladares noted. Yet timelines are not defined. “Hence, the tone at the top of bank supervision is critical. If the tone is to not be strict with banks, this filters down to examiners and enforcement.”

Cultural Flaws

“Simply put, we don’t have a full picture,” Jeremy Newell, senior fellow of the Bank Policy Institute (BPI) and founder of Newell Law Office, stated in May 24 testimony to a subcommittee of the House Oversight Committee. “What the Federal Reserve has provided to date is both selective and incomplete, omitting many relevant details and materials and glossing over key information about how, why and by whom various supervisory decisions were made.”

With the disclaimer that the opinions are his own, Newell contended that “serious problems in supervision” were not fully elucidated in the Fed’s report, and that “supervisors were principally focused on the wrong issues, occupied with processes rather than material risks, and were plenty assertive – just not about the risks that were SVB’s undoing.”

Among Newell’s takeaways: “Supervisors failed to enforce important enhanced prudential standards in the areas of liquidity and risk management that were applicable, even though they were well aware that SVB was not in compliance with them”; and the supervisory rating frameworks “were by design highly subjective and grounded in examiner judgment, with the result that SVB’s exam ratings over time often bore no relationship to its actual risk profile.”

Jeremy Newell: A culture “distracted from its core mission.”

Newell called out “a larger culture of bank supervision that has increasingly lost its way, becoming distracted from its core mission of scrutinizing bank safety and soundness and resembling something more akin to examination-as-management consulting.” The necessary reforms “don’t simply involve ‘tougher’ supervision or more rules, but instead a broader structural reform of supervisors’ approach that is aimed at ensuring that examiners are better directing their attention and already-considerable supervisory tools to the kinds of core risks to bank financial integrity that led to SVB’s failure.”

Not Yet Revealed

Akin to Rodríguez Valladares’ interrogatories, Newell called for public release and/or independent review of a laundry list including supervisory materials thus far withheld by the Fed; “internal Federal Reserve correspondence, interview transcripts or notes and/or other internal materials on which the assertions or conclusions” in the SVB report are based; assessment of the Fed’s “assertion that changes in supervisory policy in recent years led to slower action by supervisory staff and a reluctance to escalate issues”; and analysis of whether supervisors’ approach to interest rate and liquidity risks was consistent with that of other Federal Reserve districts.

Newell co-authored with BPI senior fellow Patrick Parkinson, a former director of the Federal Reserve’s Division of Banking Supervision and Regulation, a blog titled A Failure of (Self-) Examination. They boiled the failings down to:

- A misguided supervisory culture heavily focused on compliance processes and governance and not actual risk to safety and soundness.

- Reliance on an MRA apparatus that lacked prioritization or appropriate focus.

- A failure to enforce important prudential rules that were clearly applicable.

- Use of supervisory rating frameworks that were, by design, grounded in little more than examiner judgment.

“Taken together,” Newell and Parkinson wrote, “these four supervisory failures point the way to clearly needed supervisory reforms that the report barely discusses, and that Vice Chair Barr’s key takeaways from the report do not even acknowledge.”

Separately, under the heading Omissions and Surprises in the Federal Reserve’s SVB Report, BPI president and CEO Greg Baer said “the report was not designed to cover, among other things:

“Actions by the Federal Reserve as lender of last resort or market liquidity provider; actions by the Federal Home Loan Bank System; the impact on bank balance sheets of the Federal Reserve’s policy of quantitative easing followed by rapid increases in rates; actions by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., including resolution of SVB; the systemic risk exception approved by the FDIC, Federal Reserve Board and Treasury.

“Those topics presumably await review by others.”

Proposed Prescriptions

BPI on June 9 put forward Policy Recommendations Related to the 2023 Banking Stress, along with an argument that higher capital requirements for all banks are unwarranted because SVB, Signature Bank and First Republic Bank were idiosyncratic outliers. As Baer put it: “We reject proposals by some that attempt to fit their favorite policy pegs into the unusually shaped hole that appeared in March.”

The institute made other suggestions in such areas as capital, liquidity, industry consolidation and FDIC resolution practices.

Regarding examinations, it said supervisory rating frameworks should be “more transparent, better integrated with existing rules, and focused primarily on financial condition and material financial risk as opposed to process, documentation and micro-governance.” And “the banking agencies should conduct a comprehensive review of current examination practices for interest rate risk and issue updated guidance.”

Topics: Regulation & Compliance