Every time a bank collapses, we hear alarm bells about ineffective risk measurement and mitigation – and, inevitably, regulators respond by adopting stricter rules. Lamentably, though, regulations like higher capital requirements fail to address properly the root of the problem: defective risk governance, culture and infrastructure.

There is, however, a different and arguably much better approach for addressing these deficiencies: the creation and implementation of a risk management quality score (RMQS) that directly assesses every bank’s risk management practices.

Potentially, the RMQS could sharply reduce the number of bank failures by fostering risk management improvements. Why should this approach be considered, and what steps can banks and regulators take to implement it?

Creating the Right Incentives for Boards and Management Teams

Boards of directors and senior management are subject to cognitive biases that drive risk-taking behavior. A focus on short-term earnings at the expense of long-term financial viability is one such tendency we see from time to time. This can manifest itself in several ways, such as having to hit quarterly earnings targets and other financial performance metrics.

Aiding and abetting this behavior fundamentally is the quality of the firm’s risk culture, governance and infrastructure.

Virtually all risk events at banks can be traced back to some breakdown at the board and senior management level relating to: (1) how risks are communicated, escalated and understood; (2) the measurement and mitigation of risk; and/or (3) a toxic risk culture. Higher capital requirements, such the new Basel III Endgame proposal, guard against the outcome of poor risk management, but do not strike at the heart of the problem.

Establishing a risk management quality score that is used to set risk-based deposit insurance premiums – as well as to determine dividend policy, company growth and management incentive compensation plans – would limit existential risk events and greatly improve risk management practices overall.

Learning From Big Pharma

Precedent exists for such a rating process from the pharmaceutical sector, another highly-regulated industry. In 2022, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) established a Quality Management Maturity (QMM) rating system designed to foster a risk-aware mindset in the pharma industry.

The QMM was designed to help reduce risks to the drug supply chain by rating the quality of processes used in manufacturing drug products. While the program currently is voluntary, ratings are based on five protocols:

- Management Commitment to Quality

- Business Continuity

- Advanced Pharmaceutical Quality System (PQS)

- Technical Excellence

- Employee Engagement and Empowerment

Bank regulatory agencies could create a similar type of rating system based on the following pillars:

- Quality of Risk Culture

- Quality of Risk Governance

- Quality of Risk Infrastructure

Currently, the CAMELS rating process used by regulators is insufficient to provide the direct feedback on risk management banks desperately require. The “M” component of CAMELS is too diffuse to have any significant impact on changing management behavior and attitudes toward risk management. What’s more, the ratings themselves have proven over the years to be lagging and imprecise indicators of actual bank risk.

Clifford Rossi

To establish a numeric RMQS, one can use a series of criteria describing a firm’s risk infrastructure (e.g., data, systems, controls and people), culture and governance. Such ratings could be used in combination with a bank risk management exposure rating that assigns a numeric score for major risk types and their subcomponents: financial (e.g., credit, market, liquidity), nonfinancial (e.g., operational, model, reputation, regulatory and compliance) and nontraditional (e.g., climate).

Combining the RMQS with a risk management exposure rating would provide a mechanism that aligns with an age-old mantra of regulators: build risk management capabilities ahead of growth.

Implementing Risk Management Quality and Exposure Ratings

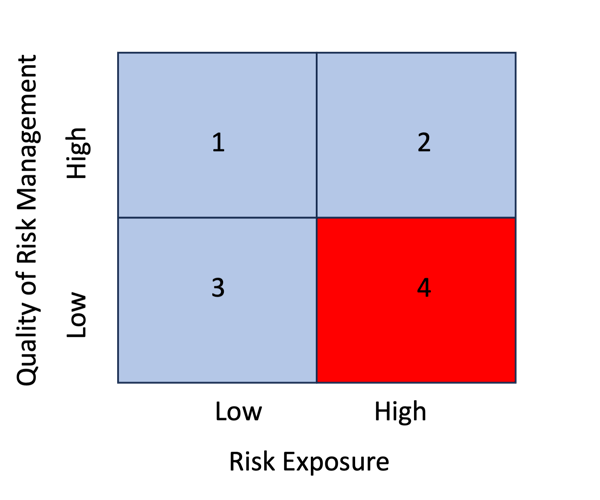

The figure below illustrates in a simple 2x2 matrix how the RMQS risk rating structure would work.

Risk Management Quality & Exposure Matrix

In the matrix, scores for risk management quality and exposure are divided into four quadrants.

Institutions that score high on risk management quality (quadrants 1 and 2) would be permitted to take on higher risk exposures, for example, and be subject to lower deposit insurance fees and allowed full bonus targets for management.

Firms scoring out in the red quadrant (exhibiting poor risk management quality and high-risk exposures), on the other hand, would not be permitted to expand their business or risk exposure. They would also face higher deposit premiums – and bonuses would not be permitted until the bank’s risk management ratings were improved to a designated level.

To bring this concept to life, let’s suppose SVB’s regulators had such a scoring system in place in the years before the bank’s demise. Based on information from the Fed’s report on SVB, along with financial disclosures by the company, the bank would have scored low along all three dimensions of the RMQS – i.e., risk management quality, culture and governance.

Furthermore, SVB’s market and liquidity risk exposures alone would have scored abnormally high, placing it in the red zone on the RMQS quality and exposure matrix. Had this rating been in place before 2019, when SVB started on its startling growth trajectory, it could have directly arrested its market and liquidity risk exposure, likely preventing the bank’s collapse.

The penalty in this case would have been a regulatory ban on management bonuses until SVB’s RMQS rating had improved to a level that indicated an above average level of risk management quality.

Parting Thoughts

Despite extensive legislative and regulatory requirements on the banking industry in the wake of the global financial crisis, we continue to see banks of all sizes making headlines from major lapses in risk management that either snuffs them out entirely (as we saw in rapid succession this spring) or places them in a state of regulatory purgatory.

Looking back over decades of banking crises and scores of banks with strong brands that no longer exist, it’s clear that what drives this behavior, in a highly regulated market, is a combination of poor risk governance, culture and infrastructure.

Indeed, as long as the quality of risk management takes a back seat to other activities at banks, headline-grabbing risk events and crises will continue to take place. No amount of regulatory guidance, heightened scrutiny of certain institutions or higher capital requirements will address the root cause of these problems.

The best chance of elevating risk management capabilities across the industry is through direct scoring of the quality of risk management programs. Banks that adopt the suggested RMQS approach will be able to link their risk exposures to bank activities, deposit insurance premiums and, most importantly, management incentive compensation plans.

Clifford Rossi (PhD) is the Director of the Smith Enterprise Risk Consortium at the University of Maryland (UMD) and a Professor-of-the-Practice and Executive-in-Residence at UMD’s Robert H. Smith School of Business. Before joining academia, he spent 25-plus years in the financial sector, as both a C-level risk executive at several top financial institutions and a federal banking regulator. He is the former managing director and CRO of Citigroup’s Consumer Lending Group.

Topics: Regulation & Compliance