What does a critique of econometric analysis from the 1970s have to do with addressing climate risk today? Everything! Risk managers, forecasters and modelers need to keep the Lucas Critique top of mind as they construct models and analyze the impact of policies designed to mitigate the effects of climate change.

In his seminal work, Robert Lucas warned of the dangers of relying on models of behavior that are derived from historical correlations for predicting the impact of policy changes. Underlying any empirical regression analysis is the implicit assumption that the past is predictive of the future. But parameters derived from historical experience may not be valid when applied to a dynamic future governed by different policies and preferences - especially over long periods of time.

Climate risk modeling is particularly susceptible to the Lucas Critique, given the scale of the changes being contemplated - including carbon taxes and emission restrictions. Businesses and consumers will react to any policy initiative, potentially disrupting the estimated relationships between policy variables and outcomes observed in history.

Unquestionably, evolving governmental and regulatory policies up the ante for risk professionals tasked with managing climate change, but there are steps they can take to overcome forecasting and scenario analysis obstacles.

Plan, Execute, Revise, Repeat

Professional risk managers often highlight the need to develop plans for addressing specific risks based on the guiding principles of identification, measurement and management. Given a detailed risk management plan, companies can then determine the most efficient way to execute it for maximum effect.

The recent rollout of climate risk scenarios by central banks - including the Bank of England's June release of its Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario - will help banks assess the potential impact of climate change on both the profitability and sustainability of their operations.

Combined with detailed disclosures on emissions, the scenarios will better position investors and regulators to understand the impact that climate policy proposals will have on both the viability of individual institutions and the broader economy.

Managing climate change is no different in principle than any other risk, but there is a tacit, if not explicit, acknowledgement by all participants in this developing field that we are in uncharted waters when it comes to forecasting the impact of climate change.

The BoE has acknowledged that its scenarios will continue to change over time, as will forecasting processes. While enhancing our own macroeconomic forecasting models to accommodate climate scenarios, my team has also determined that we need to continuously add new data, equations, and forecast assumptions to make the models more robust.

Climate risk is too complex and too new a field of study to fit neatly within an established risk management framework. We won't identify all of the blind spots or understand all the assumptions we need to make until we jump into the process and start churning out - and reacting to - estimates.

Stress Testing Precedent

The situation is similar to the first bank stress testing exercises in 2009, after the Great Financial Crisis. At the time, the U.S. Federal Reserve didn't have a well-defined set of economic scenarios, and banks didn't have anywhere near the credit-loss modeling sophistication they have today.

Rather, Fed researchers quickly specified a few plausible stress paths for economic variables and asked major banks to do their best to project losses under these assumptions within a few weeks. Despite its limitations, the Supervisory Capital Assessment Program was fundamental to calming market nerves. Moreover, it blazed a trail for subsequent stress tests - including the current annual CCAR process.

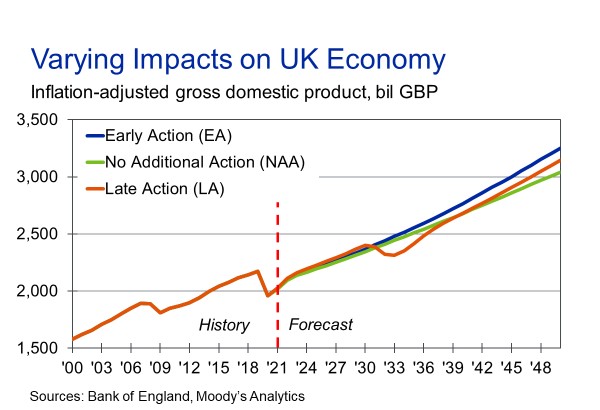

Regulators and banks are likely to follow a similar script for climate stress testing, though on a grander scale. In June, as part of its plan to understand the financial impacts of climate change, the BoE released three potential scenarios that built upon the NGFS climate scenarios: early action and late action (primarily for transitional risks) and no-additional action (primarily for physical risks).

Projected UK GDP Under BoE Climate Scenarios

Major UK banks and insurers are expected to evaluate the credit quality of their portfolios, under each of these scenarios, by October. The BoE will review the results and publish a summary report of its findings in 2022, without releasing details on individual entities.

Rather than using these scenarios to define capital thresholds, the climate risk stress tests will be used to refine and improve future tests, find flaws in the process, and note areas for enhancement.

A Forecaster's Reward

Forecasters receive validation when their projections come true. We get an extra shot of dopamine when we predict the unemployment rate for a given month - or, say, project quarterly loan originations down to the penny.

However, when it comes to loss forecasting, an equally rewarding result is seeing that our projections are so credible that they spur actions that cause the forecasts to be overly pessimistic, retrospectively. Loan origination teams may react to dire forecasts by tightening their standards, while servicing teams may double their efforts to bring down delinquency rates.

The observation that models may be subject to error resulting from the reaction of economic agents to policies and forecasts earned the economist Robert Lucas a Nobel Prize, and is critical for any credible analysis of climate change.

The Way Forward

Given the dangers highlighted by the Lucas Critique, how can risk managers proceed? The solution is twofold.

First, analysts need to be cognizant of the potential effects of the Lucas Critique when conducting analysis with existing models. We need to recognize that parameter estimates are dynamic and fluid rather than obsessing about a false sense of precision based on a specific historical episode. Analysts should regularly run sensitivity analysis. Furthermore, they should get into the habit of presenting their results as ranges, given the uncertainty in the future relationships between variables.

Second, a better understanding of the micro foundations of macroeconomic behavior will be needed to assess the impact of climate risk accurately. For example, given heterogeneity in the expected responses to a carbon tax, we will need to model the behavior of individual consumers and businesses conditional on their incentives and constraints. Summing the effects across individuals will yield a more accurate estimate than modeling aggregate behavior.

Forecasting mortgage-default risk illustrates the point. Given that climate risks are distributed unevenly across the United States, an analysis based solely on the median property value would severely under-estimate expected losses.

Properties on the U.S. coasts are not only more vulnerable to climate events, they tend to have higher property values. A detailed analysis of individual loan behavior is therefore needed to account for the nonlinearity in default risk.

Parting Thoughts

Environmental issues have risen to the top of the list of concerns at banks and other companies. The heating of the world's atmosphere poses both acute physical consequences (e.g., greater frequency and intensity of storms) and chronic issues, like the loss of agricultural productivity due to heat and water stress. While stakeholders (including policymakers, investors and regulators) agree that quantitative assessment is critical for understanding the scope and severity of the risks posed by climate change, there is no consensus on how to model these risks across countries or asset classes.

There have been, and will continue to be, some dire projections for climate change. But climate scientists and risk analysts are willing to put aside their forecasting pride for the sake of the greater good, and their hope is that the projections they make are so credible that they force individuals, companies, and even nations to take actions that avoid the forecasted outcomes.

When pondering the best approaches for forecasting and climate-risk regulation, lessons from stress testing are useful. Banks were highly skeptical of the SCAP and CCAR exercises initially. In fact, at a time when losses were piling up (in the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis), many viewed them as a waste of valuable time and analytical resources.

However, institutions eventually realized the value of these exercises. Stress tests helped to identify weaknesses in banks' processes, and, though imperfect, standardized scenario analysis yielded informative benchmarks that allowed for comparisons across institutions. Similarly, the data banks have collected during their efforts to comply with the CECL and IFRS 9 accounting standards has also proved useful.

Banks that need to comply with climate-change rules should take note of the benefits that other types of regulation have yielded. They can, moreover, learn not only from previous regulation but also from established macroeconomic theory.

One underlying lesson from the Lucas Critique is the need for humility and perseverance in any policy analysis. Given that the world is constantly changing, any analysis needs to be continuously refreshed and updated to be relevant. When it comes to driving broad change, the specific numbers won't matter nearly as much as the processes built to measure and mitigate climate risk.

Cristian deRitis is the Deputy Chief Economist at Moody's Analytics. As the head of model research and development, he specializes in the analysis of current and future economic conditions, consumer credit markets and housing. Before joining Moody's Analytics, he worked for Fannie Mae. In addition to his published research, Cristian is named on two US patents for credit modeling techniques. He can be reached at cristian.deritis@moodys.com.