Contending with the economic shocks of COVID-19 - including unemployment, decreasing revenues and high projected credit losses - banks must now overcome unprecedented credit risk management challenges. Chief among those is expected credit loss (ECL) modeling.

Banks currently face a dilemma: they must significantly step up their provisioning to account for the future impact of the pandemic, but can't use conventional loss allowance models that rely on time-series analysis and historical data. Indeed, after COVID-19 struck, forward-looking modeling assumptions that were conditioned on past experiences were invalidated overnight.

New and innovative measures are needed, because, as long as there's neither a vaccine nor group immunization - and the economy remains under threat of imposed restrictions - banks will have to provision for future credit losses related to COVID-19. However, since they are now navigating unchartered waters, it will be a challenge to comply with forward-looking financial accounting standards like IFRS 9 and CECL.

Complicating matters further is the likelihood that financial institutions will continue to suffer from the effects of lockdown conditions. The European Banking Authority (EBA), for example, predicts that the average impact of the pandemic on a bank's common equity tier 1 (CET1) ratio (which measures capital against assets) will be between 230 and 380 basis points.

While the principle of unbiased, forward-looking impairment modeling still stands, special measures are very much needed to address the COVID-19 crisis and to prevent a vicious cycle from unfolding. Firms can move forward with proper ECL planning only after considering a few important questions.

For example, what are the key characteristics of COVID-19? What impact has the pandemic had, to date, on forward-looking loss provisions, and how does this compare with loss calculations made during a standard business cycle? How will recent events influence capital management, and what specific measures are authorities, regulators and banks taking to respond to pandemic-driven ECL modeling obstacles?

When thinking about how to address all of these issues, modeling is the best place to start. Our first step is to present a basic model with a forward-looking economic index. Based on this index, loss provisions can be determined under a forward-looking regime, such as IFRS 9 and CECL.

Our model also demonstrates the impact of COVID-19, and uses the interplay of provisions and expected loss to determine the effects of the pandemic on both capital and CET1.

A Simple Model

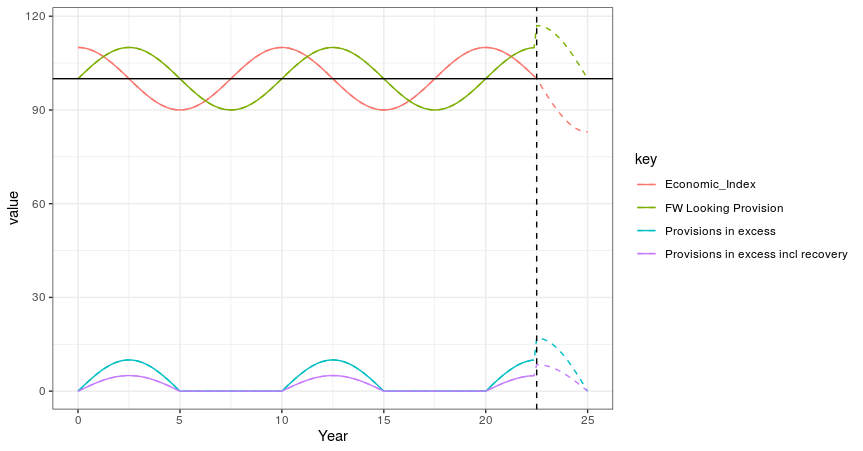

To categorize and understand the responses to the crisis by the fiscal and monetary authorities, it is necessary to comprehend the complex interplay between scenarios, provisioning, expected loss and capital (see Figure 1). Indeed, this will help substantiate our conclusions - e.g., with respect to why internal models for future scenarios are likely to break down.

Figure 1: Forward‐Looking Provisions

The red curve in the above figure shows an idealized business cycle. The black line shows (standardized) expected loss, which is depicted as a through-the-cycle average. Note that the black line crosses the red curve at its inflection points: the moments in time where the change of the business cycle performance peaks.

The green curve shows the forward-looking provisions. In this abstraction, the forward-looking provisions plateau at the inflection points: when the economy experiences the highest growth, forward-looking provisions are at their lowest point (see t = 7.5 and 17.5).

On the other hand, when the economy experiences the lowest growth, the loss provisions peak. This happens at t = 2.5 and 12.5. Thanks to the forward nature of the provisioning, at this inflection point, the bank has just experienced an above-average cycle that facilitated provisions growing toward a peak level.

COVID-19 enters at the vertical dashed line in Figure 1. The pandemic is a sudden crisis that materialized within a few weeks in the first quarter of 2020. It led to a sharp increase in provisions, because forward-looking provisions transfer the future impact to the current moment. This is true both for staged ECL approaches (like IFRS 9, which uses stages 1, 2 and 3) and continuous approaches such as CECL.

The narrative at the dashed line is that the economy is faced with a sudden negative shock, which exceeds the expected trough of the business cycle. In these circumstances, credit risks increase significantly, so that forward-looking provisions peak across business cycles, instead of within. As we'll discuss later, this has some important implications for credit risk and capital management.

COVID-19 is also an unprecedented event in the technical sense that it's bound to cause a breakdown in forward-looking models based on time-series analysis (e.g., ARMA models) and historical data.

For example, just look at the development at the right-hand side of the dashed black line in Figure 1, which demonstrates that expected losses cannot currently be accurately predicted with the help of the past behavior (see left-hand side of the dashed line) of the business cycle.

Capital Management

Figure 1 highlights the provisions in excess of expected loss in the blue curve. In times of positive “provisions in excess,” provisioning will start to eat away at Tier 1 capital - or “negative shortfall” in Basel IRB terms. This happens amid peak economic performance (where, under normal conditions and for healthy banks, it shouldn't be a problem), and builds up while a recession is developing. It peaks at the negative inflection point of the business cycle (at t = 2.5 and 12.5 in Figure 1), after which it starts to decline.

The economic devastation wrought by COVID-19 , and the subsequent lockdown, gave rise to fears that forward-looking provisioning by banks may be procyclical. A sudden, pandemic-induced rise in provisioning significantly reduces Tier 1 capital (see t = 22.5 in Figure 1) in comparison to capital changes one might see during a “normal” business cycle (see t = 12.5).

This provisioning-driven capital decrease has an impact on the lending capacity of banks, which could ultimately trigger a potential credit crunch and give birth to a vicious feedback loop. The only way this potential vicious circle can be averted is when (fiscal and monetary) authorities, banks and supervisors act in synch. This is what is happening now, with excess provisions (the blue curve in Figure 1) being mitigated by recovery measures (resulting in reduced and necessary excess provisions, captured in the purple curve).

Support Measures, and Their Impact on ECL

Regulatory, fiscal and monetary authorities and banks are pushing hard to mitigate the impact of the blue curve on the real economy. Table 1 (below) outlines all of the different approaches.

Table 1: Measures Taken by Fiscal/Monetary Authorities and Supervisors

|

Measure Nr |

Measure |

Taken by |

Aim |

Related curve |

Impact |

|

1 |

Fiscal and monetary stimulus to real economy |

Regulator and Governments |

Support businesses and aggregated demand within supply chains; government guarantees for specific “COVID-19” loans |

Red curve; making sure that economic cycle downturn is mitigated and supporting a “bounce-back” |

Smaller and shorter downturn will mitigate ECL peak |

|

2 |

Guidance to “look through” the business cycle |

Regulator |

Reduce impact of downturn of economic cycle on shortfall |

Blue curve |

Stabilizing ECL |

|

3 |

Guidance to apply transitional and specific measures |

Regulator |

Reducing ECL through a regulatory filter |

From blue curve to purple curve |

Reducing impact of ECL on Tier 1 capital |

|

4 |

Allowing banks to draw down capital buffers (capital conservation and countercyclical buffers) |

Regulator |

Reducing Tier 1 capital requirements to enhance Tier 1 excess capital |

Impact ofpurple curve on red curve |

Compensating Tier 1 impact of increasing ECL |

Interestingly, the measures are designed to address all curves within the system, including the economic feedback mechanism (from the purple curve back to the red curve), and the sudden step-up in provisions - which could trigger a credit crunch or an economic downturn.

In terms of crisis management, these measures seem to be an adequate response; however, only time will tell if they're enough. We'll have to wait and see how long-term consequences will turn out: future generations will have to pay back (through taxation) the crisis money that is spent now. Some firms, moreover, will be propped up with bank and state aid now, but will not be viable in the long run, which amounts to “throwing good money after bad.”

In the US, the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), the CARES Act (which gives banks the option to push back the implementation of CECL) and the FED's Mainstreet Lending Program are examples of fiscal and monetary stimulus (measure #1). In Europe, a good example is the ECB's €1350 billion Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), which not only provides temporary collateral easing measures but also aims to lower borrowing costs and increase lending in the euro area.

The goal with measure #2 is to guide firms to look beyond the crisis when determining ECL, and to avoid “excessively procyclical assumptions.” Toward that end, the ECB plans to provide macro scenarios to large banks to feed their IFRS 9 projections in this time of uncertainty. Since COVID-19 is an unprecedented event, forward-looking projections can no longer be exclusively informed with time-series analysis, because (as we've mentioned previously) internal time-series models are likely to break down.

Regulatory guidance for transitional and specific measures (measure #3) is intended, in part, to minimize the impact of ECL modeling on Tier 1 capital. Earlier this year, the Fed, the OCC and FDIC released a joint regulatory capital rule that should help meet this objective. The rule provides a new option to firms to phase in the effects of CECL into regulatory capital over the next five years.

Meanwhile, within the limits of its prudential authority, the ECB recommends that banks make use of the IFRS 9 transitional measures. Collective (sector-wide) forbearance measures, the ECB elaborates, do not necessarily qualify as a Significant Increase in Credit Risk (SICR), and hence do not automatically trigger a stage transition in the IFRS 9 framework.

The temporary capital and operational relief that the ECB is providing in reaction to COVID-19 is an example of measure #4. The ECB has relaxed its capital conservation buffer (CCB) requirement and expects that national macroprudential authorities will relax the countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB). The central bank has quantified that the capital relief will amount to €120 billion within the ECB-supervised banks, and that this would increase banks' lending capacity by €1.8 trillion.

Likewise, the Fed has announced a temporary relief for its leverage ratio rule.

Stay Unbiased

It is debatable whether additional flexibility with regard to the ECL computation is necessary. It is probably best, though, to stick with the principle that the ECL calculation should be unbiased. This means that any manipulation beyond the incorporation of fiscal and monetary support measures is not advisable.

Inadvisable manipulation would lead to arbitrary ECL figures that are difficult to compare across financial institutions. Moreover, loss provisioning would likely be underestimated, potentially leading to a future crisis of confidence that would wipe out any short-term gains from biased (manipulated) ECL calculations.

After the crisis itself and the response by authorities and regulators, it is up to the banks to adjust their ECL assumptions accordingly. Since the ECL is the expected credit loss after weighting the impact of (at least) three scenarios - optimistic, normal and pessimistic - the weighting scheme is crucial when adjusting for COVID-19 crisis factors.

Banks today are, not surprisingly, shifting more probability toward the pessimistic scenario. However, there's more that needs to happen than only adjusting the weighting scheme. The forward‐looking scenarios themselves have changed. The COVID-19 crisis, as demonstrated in Figure 1, is far from a “normal” downturn in a business cycle.

Rather, it is a reaction to an external (health-related) shock with an unknown recovery pattern. Therefore, for loss projections, it is best to acknowledge that we are seeing something new and rely on a mix of internal projections and external sectoral projections - instead of simulating from internal data with some kind of time-series model (e.g., ARMA). Recent anecdotal evidence suggests that banks prefer to use their own projections, enriched with an expert filter and inspired by external sectoral forecasts.

For comparability of ECL calculations, it is important that regulators start to publish survey results on ECL parameterization - particularly those that highlight industry practices for the speed of mean reversion.

Challenges Ahead

Impairment processes are likely to be developed (or redeveloped) to accommodate supervisory responses - e.g., the distinction between sector-wide moratoria and specific moratoria. Moreover, a distinction must be made between structural causes to financial distress (and arrears) and COVID-19-related causes. Given its accuracy and timeliness, integrated payment data can help with this distinction.

Risks are shifting due to the COVID-19 crisis. Entire sectors are under threat, and due diligence is needed more than ever. For example, before issuing a loan to an SME, some key questions need to be asked: What is the quality of the SME's management? Moreover, can they adapt their products and retain their existing business, or do they need to develop new offerings?

There is much anecdotal evidence of small business adaptability. For banks, it is important to gather the behavioral characteristics of their customers (like SMEs) and reflect them in the ECL calculations - particularly in the conditional PDs. Banks also need to integrate internal and external sectoral projections to “look-through” crisis, and anticipate possible upswings.

When it comes to surveying and divulging industry practices (especially with regards to “bounce-back” or mean-reverting parameterization), regulators also have an important role to play.

Only time will tell whether all of the actions taken, to date, will be enough to manage the current crisis. More measures for responding to pandemic-driven ECL modeling challenges will likely emerge in the future. For the moment, the coordinated efforts of authorities, regulators and banks is the best we can do.

Dr. Marco Folpmers (FRM) is a partner for Financial Risk Management at Deloitte The Netherlands. He wishes to thank Alexander Marianski, associate director of Deloitte UK, for kindly providing feedback on an earlier draft of this article.