How should we handle stress testing when we are already experiencing stress? If the objective is to identify weaknesses before shocks happen, we might conclude that there is limited value to running a stress test in the middle of a recession. But that would be shortsighted.

The recent release of the Federal Reserve's CCAR scenarios provides an informative case study, given that the economy remains under considerable pressure.

The fact is that there is always a possibility of further downside, regardless of the current state of the economy. Understanding how a portfolio or company might perform if a bad situation gets worse can mean the difference between deciding to keep our ship on course in the middle of a storm or ordering the crew to head for the lifeboats.

While every downside scenario is possible, not all of them are worth our consideration. From the Federal Reserve's safety and soundness perspective, the implicit assumption may be that banks should have at least enough capital to withstand 95% of possible economic outcomes. So, we might define plausible stresses as those that are expected to occur less than 5% of the time.

What is a Stress Event?

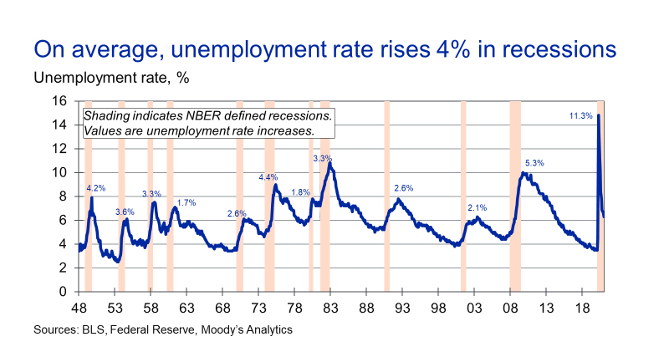

History can provide us with a useful starting point for defining stress events. We focus here on the U.S. unemployment rate, which has the benefit of having been measured through multiple economic cycles, with monthly observations going back to 1948.

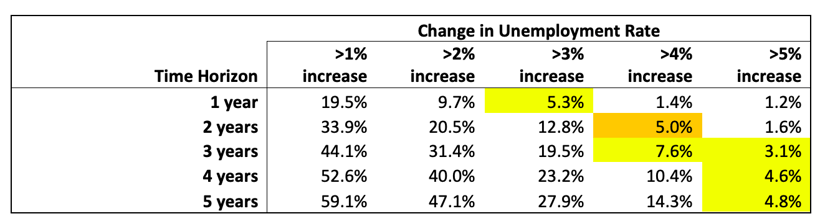

To get a sense of the distribution of changes in unemployment across the economic cycle, we calculate the number of times the unemployment rate has risen by varying amounts over varying time horizons. (See Table 1.)

Using a 5% probability threshold, we can define a stress event as a 3% increase in the unemployment rate within 12 months, a 4% increase within 24 months or a 5% increase within 48 months. A one-year period may be too short to adequately assess bank portfolios, but the uncertainty over a 4-year period may be too large. Given that most credit losses are typically realized within a two-year forecast horizon, a stress test defined as a 4% increase in the unemployment rate over 24 months is reasonable.

This matches closely with the Fed's scenario design. The Fed also specifies that the peak unemployment rate under its severely adverse scenario should be no lower than 10% - its high during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and close to its post-World War 2 peak up until 2020.

Unemployment Data: The North Star of Stress Testing

Setting an absolute minimum floor on the unemployment rate introduces a countercyclical component. When times were good - as they were at the beginning of 2020, with an unemployment rate of 3.5% - the stress test defined a larger relative increase (+6.5%) than it did, for example, when the unemployment rate was 5.7%, at the beginning of 2015.

When the unemployment rate is already elevated, as it was at the start of this year's stress test, we'll want to consider where we are in the economic cycle - along with the outlook for fiscal and monetary policy. A situation where unemployment is high and rising will present different challenges than when it is high but falling. In the first case, the risk of additional unemployment increases may be compressed; in the latter case, the risk may normalize or even expand.

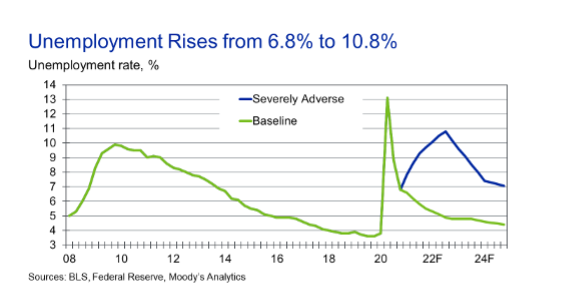

An example from recent history is illustrative. The unemployment rate for the fourth quarter of 2020 was 6.8%, compared with 8.8% in the third quarter. To ensure that this positive momentum hasn't led to excessive risk taking, it's reasonable in a 2021 stress test to consider an average increase in unemployment. This is consistent with this year's CCAR stress test (see Figure 2), where the Fed set the peak unemployment rate at 10.8%, exactly 4% above its starting point.

If the unemployment rate had increased in the fourth quarter of 2020 (while “automatic stabilizers” such as unemployment insurance were supporting households and businesses), it might have been reasonable in a 2021 stress test to expect future incremental increases in the unemployment rate to slow. Under such a scenario, a lower-than-average +3.2% increase in the unemployment rate, causing it to peak at 10%, would define a reasonable stress test.

The Importance of Mitigating Tail Risk, and the Consequences of Fed Intervention

Risk management calculations are much easier to solve when we can explicitly define or limit the tail risk. With its scenario design, the Federal Reserve is effectively signaling that it is the ultimate insurer that will intervene to preserve the financial system if the economy goes beyond the 95th percentile defined by its stress tests.

This is a reasonable social contract that leads to a more efficient outcome than if each bank had to hold enough capital to guard against all potential shocks. Without it, banks might become so capital-constrained that they would do very little lending or might significantly underestimate their risks, setting themselves up for failure, a la the GFC.

But there are two sides to every bargain. In exchange for this tail-risk insurance, we need to allow the Fed to unwind its accommodative policies and for the government to raise taxes once the economic storm has cleared. This prevents the economy from overheating and allows our institutions to replenish their resources in advance of the next crisis.

Arguably, that normalization was never completed after the GFC. Time will tell if investors, businesses and households are more willing to “pay the price” this time around. If normalization doesn't occur, then the argument for reducing the relative severity of stress scenarios during a recession will be harder to justify.

In a world with no Fed tail-risk intervention, stress test scenarios would need to be designed to do exactly the opposite, with “risk expansion” pushing unemployment up exponentially during a contraction. Indeed, amid a crisis with no government-supported rescue plans, the economy would enter a vicious downward spiral as business failures would lead to job losses, which would in turn lead to more bankruptcies.

While we may discount the likelihood of a such an extreme scenario given the success of monetary and fiscal policies recently, conducting a stress test that assumes no government support may be just the dose of reality that portfolio managers, investors and policymakers need to steer the economic ship away from the sirens' call of low rates and cheap money.

Preparation is important but, ultimately, the value of a stress test is to keep us from getting complacent. We don't want to make the mistake of confusing risk-free yield with yield-free risk.

Cristian deRitis is the Deputy Chief Economist at Moody's Analytics. As the head of model research and development, he specializes in the analysis of current and future economic conditions, consumer credit markets and housing. Before joining Moody's Analytics, he worked for Fannie Mae. In addition to his published research, Cristian is named on two U.S. patents for credit modeling techniques. He can be reached at cristian.deritis@moodys.com.