Nearly every civilization since antiquity has developed the concept of a “trickster.” This god, spirit, demon or spirit animal plays tricks on unsuspecting humans to tempt them, test them, or just cause trouble.

For risk managers, it may seem as though financial regulators and auditors are the modern-day tricksters. These overseers force financial institutions to develop complex models and systems for running regulatory stress tests and expected loss calculations, only to be challenged by the regulators' own models and projections.

Given all the time and energy required to comply with these regulations, we might ask, if regulators' views always prevail in the end, what's the point of all of the resources firms currently devote to internally-developed models for stress testing? Wouldn't it be more efficient and transparent, and far less costly, for the regulatory authorities to simply publish and run their own centralized stress testing analyses, and to then report out the results?

Similarly, financial reporting under CECL or IFRS 9 could be simplified by the publication of “official” lookup tables of expected losses. If regulators are going to run their analyses anyway, why do we force each institution to create its own parallel process?

It's Tricky

It's a fair question that regulators have struggled with since the beginning of time. A dictated or formulaic process may be more transparent and easier to implement, but it runs the risk of becoming outdated quickly. Just as individual businesses need the freedom to react to changing market conditions rapidly, so, too, do regulators.

Of course, a completely opaque process has its own costs. If regulatory forecasts are entirely unpredictable and subject to seemingly random volatility, the ability of institutions to plan will be inhibited.

Moreover, given regulatory uncertainty, lenders may hold excess levels of regulatory capital - just to be safe. While this excess conservatism sounds appealing from a safety and soundness perspective, it can starve businesses of the credit they need to grow, with meaningful consequences for employment and incomes.

Valuing the Process

Regulators need to walk a fine line between dictating stress testing processes and providing financial institutions with enough freedom to assess their risks accurately. Like any risk management process, they must first clearly identify their objective. In the case of stress testing, regulators' primary goal is to ensure that the financial system has enough capital to survive a severe economic shock.

Given the ambiguity of what a “severe” economic shock looks like, the stress testing process is more informative to regulators than the calculated results. Preparation of a stress test requires firms to invest in data collection, processing, modeling and analytical functions. These capabilities may be more valuable from a risk management and control standpoint than the level of capitalization.

Consider the case of two hypothetical banks: one has a large capital buffer but poor internal controls, the other has less capital but a strong risk management culture. Which institution will perform better in a crisis?

History shows a strong correlation between bank failures and ineffective internal controls or poor risk management. Capital buffers are important for guarding against unexpected events, but they can give a false sense of security if an institution has a poor understanding of its risks.

Comparability and Accuracy

This is not to say that expected loss estimates under stress don't matter. They absolutely do, and are particularly important for a central bank or other financial regulator that is focused on identifying broad systemic risk.

One challenge facing regulators in designing their stress testing frameworks is the tradeoff between accuracy and comparability across regulated institutions. Comparisons are tricky, but regulators certainly want to comprehend the idiosyncratic risks unique to each institution.

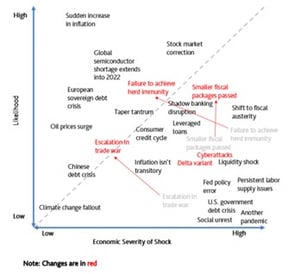

To understand this, a regulator might ask each institution to consider a risk matrix of broad economic threats to identify their own 95th or 99th percentile tail risks - and to run a stress test under those conditions. For example, a stress scenario for a bank that does a lot of lending to the automotive industry might look quite different from a bank that finances the tourism industry.

An Economic Risk Matrix for July 2021

Source: Moody's Analytics

Though insightful, the drawback of this supervisory approach is that it makes comparisons difficult. Calculating the likelihood of “automotive industry stress” occurring versus “tourism industry stress” is not only complex but also dependent on a host of macroeconomic assumptions.

Though insightful, the drawback of this supervisory approach is that it makes comparisons difficult. Calculating the likelihood of “automotive industry stress” occurring versus “tourism industry stress” is not only complex but also dependent on a host of macroeconomic assumptions.

Alternatively, a regulator could define specific economy-wide scenarios to be used by all financial institutions to assess their loss exposures under stress. Under this method, some institutions will be hit harder than others, depending on the nature of the proposed scenarios.

The advantage of a common-scenarios approach, however, is that it allows for benchmarking of bank portfolios across industries and lending products. For a regulator with a mandate to assess economy-wide shocks, this approach provides a better method for identifying specific institutions and lending activities that could produce disproportionate losses in a downturn.

Staying in Your Lane

Given their broad mandate, the Federal Reserve and other central banks require large, complex financial institutions to stress test their portfolios under both common and idiosyncratic economic scenarios. A testament to the value of this process is the number of institutions that now conduct their own independent stress tests voluntarily, to assure shareholders, customers and other stakeholders of their financial viability.

Seeing the value of a common stress test in terms of both improving institutional risk management capabilities and allowing for cross-institution comparisons, what's the right way to go about it?

Again, the answer involves striking a balance between providing enough scenario guidance to ensure consistency and allowing for enough customization to produce a meaningful test. The fact that regulators allow for some stress testing flexibility is an implicit acknowledgment that they can't possibly know the intricacies of regional economies and individual borrowers the way that local institutions and other specialized firms can.

Indeed, while remaining consistent with their broader objectives, regulators can spark innovation in the development of forecasts by not providing certain scenario details.

Take the case of assessing the risk of auto loans in the United States. For banks with large exposures to auto loans, assumptions on future values are critical for assessing both the likelihood and severity of their losses. But the Federal Reserve does not provide a forecast of used car prices as part of its annual CCAR stress-testing process. To bridge this gap, banks need to develop innovative internal models for forecasting car values that are consistent with the variables the Fed does provide - such as GDP and unemployment.

Similarly, although it instructs institutions to consider local economic conditions when estimating stress losses (particularly for loans backed by residential real estate), the Fed does not provide scenarios at the state or metropolitan-area level. By not providing local forecasts, the Fed can encourage research and innovation in this area, while still leaving open the option to challenge assumptions that may be inconsistent with their national-level guidance.

Parting Thoughts

Is it better to centralize or decentralize risk management? Organizations - and society at large - have struggled with this question for centuries.

As usual, the answer lies somewhere in the middle. To allow for systemwide analysis and to ensure comparability across institutions, we need some centralization of broad objectives and guidelines. On the other hand, to allow individual institutions to better assess their own unique situations and to encourage continuous innovation, we also need some decentralization.

Regulatory authorities can play an important role in facilitating innovation, via identifying and sharing best practices throughout the industry. Financial institutions should be competing on the price and quality of their services - including better loan underwriting, servicing and portfolio management. They should not, however, be competing on the best way to execute a stress test or produce an expected loss forecast for financial reporting. An open exchange of processes and ideas on these topics is therefore in everybody's best interest.

The centralization versus decentralization question also applies to individual companies. Here, too, we see the benefits of a hybrid approach. At a bank, for example, individual business lines may use different forecasting techniques, based on characteristics unique to each portfolio. But they should be complemented by a centralized risk oversight team that can outline objectives and requirements, while also playing a key coordination role in compiling and summarizing results.

Like an external regulator, a centralized risk team's broad visibility across the organization allows it to identify areas of strength and weakness. The risk team can also assist with internal information sharing across departments, to increase quality, consistency and efficiency.

Circling back to our original point, when regulators provide stress paths for only a few key economic indicators, while instructing institutions to figure out the rest, should they still be considered tricksters?

Tricksters have a bad reputation for creating chaos and leading individuals to make poor decisions. But a closer read of trickster stories often reveals their noble intentions. Their “tricks” and trials made mythological heroes stronger or caused them to question their assumptions. Regulators should embrace this role, with a similar intent, when designing stress testing and other regulatory exercises.

Cristian deRitis is the Deputy Chief Economist at Moody's Analytics. As the head of model research and development, he specializes in the analysis of current and future economic conditions, consumer credit markets and housing. Before joining Moody's Analytics, he worked for Fannie Mae. In addition to his published research, Cristian is named on two US patents for credit modeling techniques. He can be reached at cristian.deritis@moodys.com.