The Current Expected Credit Losses (CECL) accounting standard may have enabled a quicker reaction by banks to the pandemic economy, but whether it successfully bolsters lending during downturns is still to be determined, according to a Federal Reserve study.

Taking effect January 1, 2020 for most large and midsize U.S. banks, CECL was put to “an immediate test . . . during an economic downturn and recovery, albeit an unusual one,” said the December FEDS Notes paper by a five-author team including principal economists Ben Ranish and Cindy M. Vojtech.

CECL was designed to make loan-loss provisioning more proactive and less procyclical than under the previous incurred loss methodology (ILM).

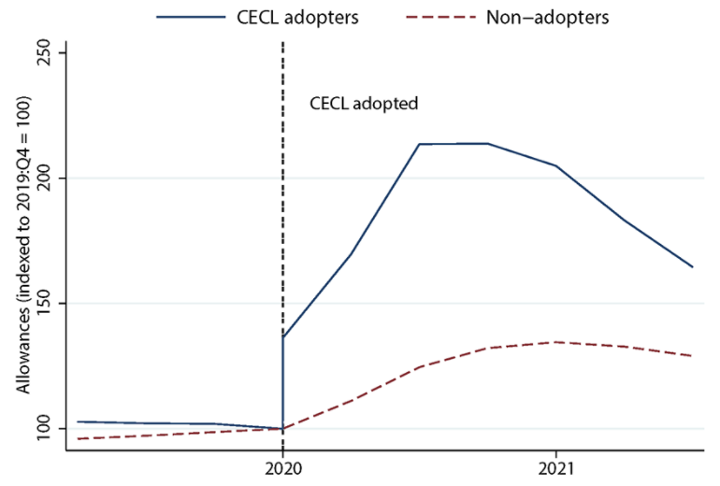

Estimating losses over the lifetime of loans immediately increased banks’ allowances by 37%, the Fed research said. “Not counting the adoption impact,” it added, “allowances increased by 76% in the first half of 2020 relative to 2019 Q4 levels. In comparison, non-adopters' allowances increased by only 32% over the same period.”

Federal Federal Reserve economists chart the jump in banks’ allowances after CECL took effect.

Federal Federal Reserve economists chart the jump in banks’ allowances after CECL took effect.

While differences between those bank groups could account for some divergence, “the pandemic experience suggests that CECL generally increases the responsiveness of provisioning for credit losses to changes in economic outlook,” the economists wrote.

There was “a wide range of impact on allowances for different loan types. However, we find limited evidence that the impact of CECL on allowances is associated with decreased lending in the pandemic.”

Crisis Reaction

CECL was developed by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in reaction to the Great Financial Crisis, when low bank allowances early in the crisis climbed and reached a peak around 2010, constraining bank lending as the economy struggled to recover. CECL aims to reduce such procyclicality by giving banks more ability to take anticipatory, precautionary steps to build allowances as credit risk rises.

The Fed report acknowledged that the sharp change in economic outlook presented by the pandemic made it “difficult to determine the cyclicality characteristics of CECL,” and there is little evidence of CECL’s impact on loan growth.

Laurent Birade, industry practice lead for risk and finance integration at Moody’s Analytics, said his research indicated that banks would ramp up allowances as good times start to fade, maintain them as the economy soured and charge-offs increased, and release them sooner at the economy starts to recover. That’s essentially what happened during the pandemic, except charge-offs were minimal due to massive federal financial assistance.

Minimal charge-offs meant loan collateral values remained stable, one reason banks have remained relatively healthy, according to Michael Gullette, senior vice president, tax and accounting at the American Bankers Association (ABA).

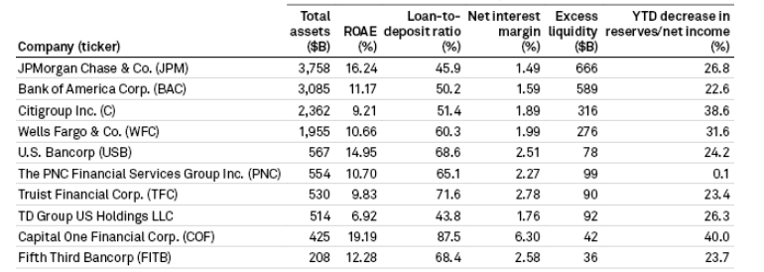

“Reserve releases provided a huge tailwind for bank earnings through the first nine months of 2021, with reserving declining by $51.2 billion between the fourth quarter of 2020 and the third quarter of 2021” as conditions improved, said an S&P Global Market Intelligence analysis in early January, ahead of year-end earnings reports. “We expect banks to reduce reserves by another $6 billion in the fourth quarter of 2021, but only increase reserves by $1.3 billion in 2022.”

S&P Global Market Intelligence shows loss reserves at the 10 biggest U.S. banks declining through 2021’s third quarter.

“Forecasting of collateral values is the biggest issue in CECL,” the ABA’s Gullette said. If they are falling or forecast to go down, “we’ll start to see huge provision increases, much bigger than what we saw in 2020.”

More timely reserving would be a beneficial outcome of CECL.

“You’re bringing the balance sheet closer to a market-to -market condition, and this is probably the closest you can get to adapt to deteriorating economic conditions,” Birade said.

A Different Perspective

The ABA gives CECL less credit for the rapid increase in allowances. A January viewpoint co-written by Gullette noted that the Fed study did not mention that banks which didn’t adopt CECL had higher coverage ratios prior to 2020 than did their larger counterparts, and that higher starting point diminished their percentage increases.

“With this in mind, the median first-quarter 2020 allowance coverage ratio for commercial real estate, the mainstay of most community bank businesses, was actually higher for non-CECL banks than for CECL banks,” the ABA said. It added that regulators’ pushing banks to increase allowances as the pandemic unfolded, regardless of what the quantitative models indicated, also clouds CECL’s impact.

In terms of CECL’s effect on lending, the ABA and other bank representatives have expressed concerns that CECL would actually increase procyclicality – that financial stress would prompt banks to rapidly increase allowances, reducing their net income and capital and thus inhibiting lending. That concern was addressed with banking regulators’ CECL regulatory transition rule that allowed adopters to effectively defer and amortize the initial regulatory capital impact. A revised version of the transition rule adopted March 30, 2020, enabled similar treatment for incremental CECL allowances after the adoption date.

The ABA said the transition rule played a major role in “neutralizing the aggregate capital impact on adopters,” and “the banking agencies should now consider how such a countercyclical measure could be made permanent.”

The Fed economists credited the transition rule with “approximately neutraliz[ing] the aggregate capital impact of CECL so far.”

Accounting-Risk Alignment

Given what it sees as the inconclusive impact of CECL on allowances and lending during the pandemic, the ABA harbors concerns about how smaller banks are affected. It noted that FASB members acknowledged community banks’ superior understanding of their borrowers, and it questioned CECL’s degree of improvement over ILM for community banks “who must bear the cost of reengineering their credit loss estimation systems and processes for 2023 adoption.”

Despite such doubts, CECL does appear to be better aligning the accounting and risk functions within banks. Birade of Moody’s Analytics noted how ILM and CECL attach different allowances not only to different categories of loans, but also within categories. A student loan, for example, may be granted over four years, followed by a 12-month job-search reprieve and then a 10-year repayment period; lenders reserve for anywhere from 18 months to four years under ILM, and for 15 years under CECL.

Similarly, some credit card maturities may be estimated at 36 months, requiring a very different CECL allowance than American Express balances that are paid off monthly. On the business side, hotels in large metropolitan areas catering to business travel suffered more during the pandemic than did those catering to recreational getaways.

“This is something CECL can pick up in its estimates,” Birade said.

“A Common Metric”

CECL provides banks with a three-part model to gauge asset risk and corresponding allowances: the mix of assets in the portfolio; their credit quality historically; and an economic forecast that includes factors such a prepayments, unemployment rates and GDP.

Moody’s clients have used that “machinery” to understand their loan portfolios better, Birade said, increasing their comfort to lend in new growth areas.

“The biggest impact of CECL may be aligning everyone within the bank to the risks of the bank’s different loans,” Birade said. “Now they have a common metric – imagine what a bank can do with that from a strategic perspective.”

Birade observed that smaller banks that have incorporated CECL into loan pricing, taking the methodology “into account for determining profitability of a loan, and then the banker will go out and try to win the best deal for the bank, a seamless way to incorporate risk into pricing.”

Better Data and Controls

Jonathan Prejean, managing director, accounting and reporting transformation at Deloitte, said that CECL can lead to better bridging between banks’ finance and risk silos.

“Now you’re really measuring the risk of loss in the portfolio, which is more of a risk management function than an accounting concept,” he said.

Incorporating the CECL methodology into bank systems and building the necessary data models has been a costly endeavor. However, Prejean said that should lead to better risk data overall, cleaner and of high quality, given it will be used for financial reporting. Plus, it will likely be aggregated in one place with better controls.

“A lot of effort is being put into creating the data to be used in those models,” he said, “so that data could obviously be used by others in the organization from a risk perspective.”