Should stress-testing downturn scenarios developed by regulators take into account potential government bailouts? If they do not, do risk modelers still need to consider what could happen to banks, investors and consumers if there is no rescue plan in response to the next crisis?

These are certainly among the issues that regulators and banks must ponder going forward, as new stress tests are created. In February, the regulatory viewpoint became clearer, as the Federal Reserve released scenarios for its 2022 Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) stress-testing exercise.

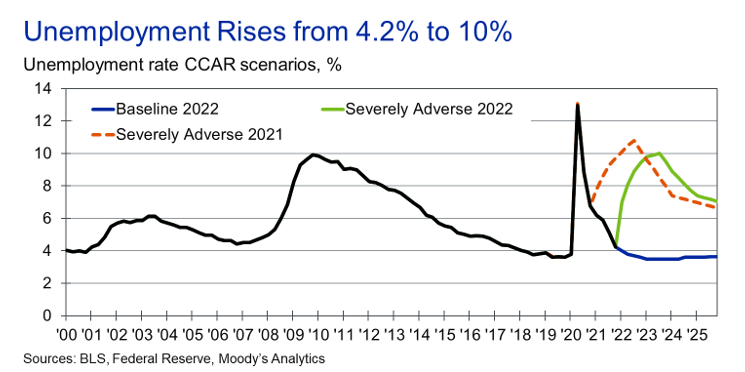

This year’s edition was similar in spirit to previous years, with the publication of two scenarios: baseline and severely adverse. The latter defined a harsher scenario than last year’s test in the sense that while unemployment is near 10% in both cases, the starting point is much lower today relative to a year ago.

Figure 1: The Fed’s CCAR Scenarios

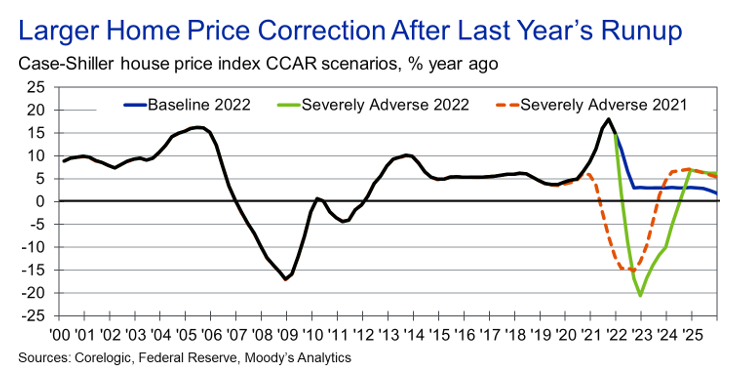

Residential real estate prices also experience a larger decline in the 2022 severely adverse scenario, primarily because prices have risen by more than 18% in the past year. Consequently, there is more room for prices to decline – at least in percentage term.

Figure 2: Residential Real Estate Projections

Despite a somewhat harsher scenario, banks should pass this year’s CCAR stress test with flying colors, given that the credit quality of their borrowers remains strong and that credit losses during the pandemic came in far lower than anticipated, keeping capital levels healthy. Nonetheless, because of inflated market values for real estate, equities and other assets, significant risk to banks’ financial health remains. Moreover, rising inflation, high energy prices and geopolitical risks pose significant risks to growth and labor markets.

Missing Moral Hazard

Absent from the Fed’s 2022 stress-testing guidance is any consideration of moral hazard and other psychological risks that have developed after unprecedented levels of fiscal and monetary support were injected into the economy in 2020 and 2021.

Few analysts would argue that the government’s response was not justified, given the size, scope and uncertainty of the pandemic-induced recession. By all accounts, without government intervention, households and businesses would have been devastated, the recession would have been much more severe, and the recovery would have taken much longer. But time will tell how effective these programs really were.

Banks and other lenders were obvious beneficiaries of the support. They experienced declines in their losses instead of increases – something unheard of during prior recessions.

While government actions avoided an economic catastrophe on top COVID-19’s human toll, at what cost? Have we set expectations that the U.S. Congress and the Federal Reserve will always come to the economy’s rescue in the future? The moral hazard risk of the “Powell Put” and the $2.2 trillion CARES Act is that they may encourage excessive risk taking that leads to a large crash in the future.

Indeed, this idea isn’t so far-fetched. From an empirical perspective, we now have two data points – the Great Recession and the COVID-19 Recession – where the federal government came riding to the rescue.

Given this track record, some risk analysts might argue that it would be unreasonable not to build an aggressive government response into a downturn scenario. If the Fed’s severely adverse scenario were to play out today, do we believe officials would sit back and allow the economy to plummet? Even with our divisive politics, it’s doubtful.

Problems Either Way

Econometrically, risk modelers face a proverbial Catch-22. If they ignore the exceptionally low loss performance experienced during the pandemic in their calculations, then they are excluding one of the most severe recessions in U.S. history (as measured by quarterly declines in GDP).

If instead they include the pandemic period in their estimation data, then they are implicitly assuming that a similar level of government support would be provided in a future downturn. Under this scenario, the effect of rising unemployment would be expected to be more than offset by higher unemployment insurance benefits, stimulus checks, low interest rates and quantitative easing. Future foreclosure and eviction moratoriums wouldn’t be out of the question either.

Hope for the Best, Prepare for the Worst

While this is a reasonable line of logic, prudent regulators and firms will want to assume a worst-case scenario for CCAR. That is, they will consider what would happen to loan defaults if the economy experienced a large shock and no one came to the rescue. Could bank balance sheets survive such an event on their own?

Some may complain that this assumption is unrealistic, given history. However, the Fed is first to acknowledge that its severely adverse scenario is not intended to be a forecast. Rather, it is a “hypothetical scenario designed to assess the strength and resilience of banking organizations.” Fiscal and monetary policies would probably try to act in such a situation, but there is no guarantee that they will have the means to do so or if they will be successful.

One way to break out of this moral hazard situation would be to actually go through a downturn wherein government authorities either refuse to or are unable to act. “Tough love” would reset expectations – but at great cost to the most vulnerable households and small businesses.

A less costly approach involves constant communication and conditioning of our collective psyche. Households and investors need to believe that the 2020 government response was truly a unique, once-in-a-lifetime event. Automatic stabilizers can be expected to kick in during the next downturn, but nobody should count on extraordinary measures.

For this plan to be successful, persuasive risk managers will be needed to convince individuals and businesses to resist the temptation to rely on future government bailouts.

The value of human risk professionals who can look beyond the data is unquestionable, as artificial intelligence and machine-learning algorithms could mistakenly supercharge risk-taking based solely on the historical record, leading to greater volatility and increased tail risk. The algorithmic trading that now dominates equity markets already demonstrates this tendency toward boom-bust behavior.

Parting Thoughts

Institutionalized stress testing was one benefit that came out of the Great Recession. Despite repeated calls to eliminate or weaken CCAR and the Dodd-Frank Act Stress Testing processes, their survival was one reason why financial institutions were well capitalized going into the COVID-19 Recession.

To improve upon the existing process, we need to acknowledge that regulators, including the Federal Reserve, play a unique role in the stress testing process as both referees and protagonists.

In times of economic stress, regulators assume the role of firefighters – adding liquidity, extending credit lines, and easing off regulatory requirements to allow banks to preserve capital and minimize losses. Once the fire is extinguished, emergency measures should be suspended and the role should shift to that of the fire inspector, with regulators reviewing balance sheets, running simulations to identify weaknesses, and issuing fines, if necessary.

Given this dual role, risk managers need to do the one thing during this year’s stress tests that they may be reluctant to do at any other time – ignore recent history. Only by remaining extremely vigilant in the good times, and resisting the temptation to reduce stress testing or relax lending standards, can risk managers minimize the need for future government bailouts and break the cycle of moral hazard.

Cristian deRitis is the Deputy Chief Economist at Moody's Analytics. As the head of model research and development, he specializes in the analysis of current and future economic conditions, consumer credit markets and housing. Before joining Moody's Analytics, he worked for Fannie Mae. In addition to his published research, Cristian is named on two US patents for credit modeling techniques. He can be reached at cristian.deritis@moodys.com.