The 2022 digital asset crash wiped out more value than the $1.7 trillion during the burst of the dot-com bubble in 2000. The aftermath of the $3 billion-plus cryptocurrency seizure connected with the Silk Road fraud, the FTX collapse and countless other crypto and stablecoin cases are still to be added up. Investigations or accusations may result from the hindsight of politicians, regulators and others, but here we play devil’s advocate to critically think about the paradox of digital assets, to see whether its future may evolve like the “quantum cat,” i.e. simultaneously both alive and dead.

A 2019 IE University in Spain study pointed out that “existing cryptocurrencies have failed to achieve the objectives envisioned by their pioneers and would generally not be considered as money,” and “modern discussions and debates about cryptocurrencies tend to confuse ‘money’ with ‘systems of payments’ or the mechanism by which transactions are processed and settled.”

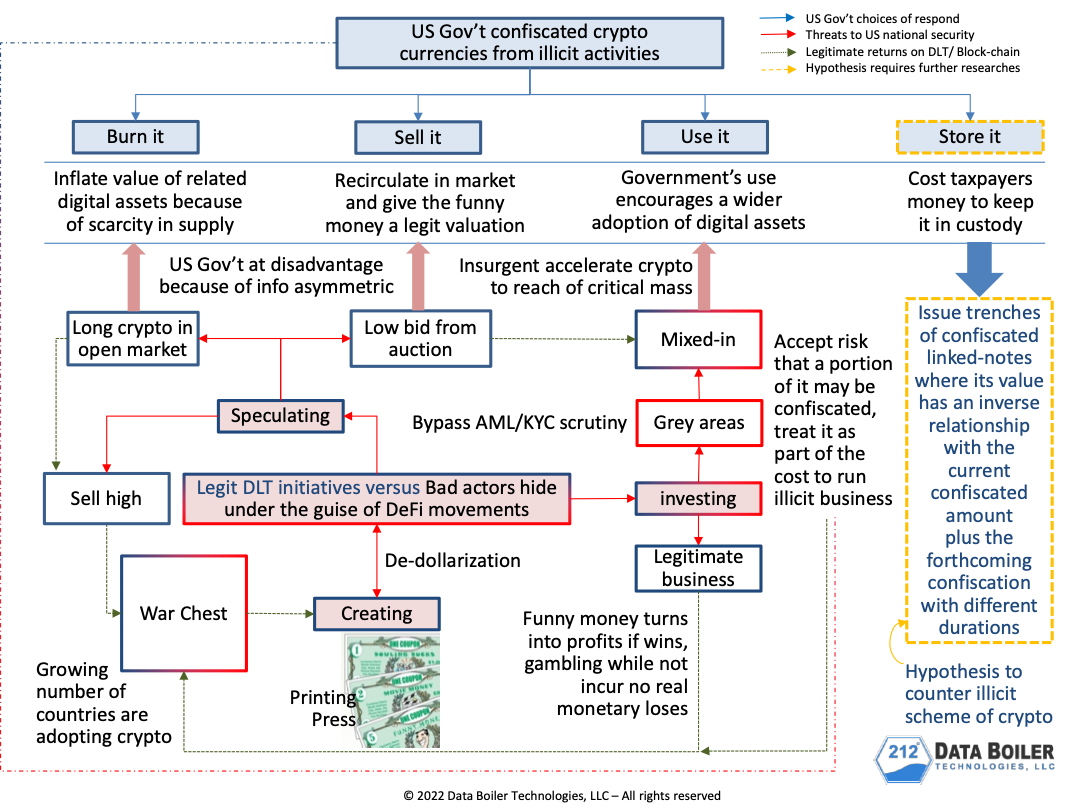

The authors seem to indicate “trust” being a crucial factor for digital assets, while those who view cryptocurrencies negatively may compare such trust aspects to a Ponzi scheme. So, as an example, we used the U.S. government-confiscated cryptocurrencies from illicit activities to showcase the trust issues regulators are facing.

As illustrated above, there is no good way in dealing with confiscated digital assets or crypto meltdown. Burn it, sell it, or use it, all lead to undesirable outcomes. The entire flow mixes in legitimate distributed ledger technology (DLT) initiatives with potential bad actors / foreign adversaries that hide under the guise of decentralized finance (DeFi) / de-dollarization movements. Funny money gets legitimized in growing the war chest and creating disadvantages for any government to curb illicit activities.

Weaknesses to Be Assessed

While we feel thankful that the Financial Stability Board, Bank of England and other authorities have compiled comprehensive assessments of risks to financial stability from digital assets, we think there are gaps in truly gauging the those risks.

For example, the “reuse” backdoor, a vulnerability due to repurposing of blockchain design components, and keylogging issues seem not to be getting scrutinized. The crypto sector seems unprepared for the arrival of quantum computing; the “51 percent attack” could be cracked open within seconds by quantum computing, making most if not all of today’s DLT-blockchain and other cryptography security vulnerable.

Questionable hard fork, insufficient attention on various pre- and post-trade transparency issues, reliability of digital assets’ market data, maturity and liquidity mismatches, stablecoins’ structure for potential redemption runs . . . the list can go on and on. Yet, none of these get as high a priority as debating among regulatory agencies on who should have oversight over the crypto markets. How sad!

Jurisdictional and Other Questions

Risks cited by CME Group (e.g. capital requirements, counterparty due diligence, financial resources for managing participant defaults, appropriate stress scenarios for sizing financial resources) concerning FTX’s settlement and custody proposal seemed addressable while never getting a chance to be enforced or implemented. Prior to the collapse of FTX, it claimed to be working with Nasdaq’s RTFY order router to source order-book liquidity at the best possible prices without relying on payment for order flow (PFOF). We wonder why no one questioned that, especially in that FTX’s U.S. president left soon after. (It is usually a red flag when senior executives abruptly part ways.)

The bigger questions that puzzle us are: Had funds been deliberately transferred somewhere else before the announced bankruptcy? Who are the real forces that gave FTX its war chest? What is their next move if they are to use the residual digital assets to resurrect in another domain(s)?

How was the Bahamas government able to tap into the substantial assets that were left behind by FTX/Alameda Research before their more powerful counterparts in the U.S. started to identify and confiscate any money? There lack orchestrated actions to address borderless digital assets’ regulatory and jurisdictional issues. Is it due to the competitive dynamic globally, or other conspiracies that this irrational exuberance in digital assets may be an intentional act to funnel billions if not trillions into the hands of powerful, well connected elites who have significant stakes in legitimate digital asset infrastructure to guarantee such transactions?

We refrain from guessing possible foreign adversaries or geopolitical figures. Our point of concern is indeed about the irony of traditional finance (TradFi) or centralized finance (CeFi) elites dominant in DLT-blockchain that is supposed to be a revolutionary way to disrupt or “disintermediate.”

Power Play?

Elite legacy players are pouring billions into building related infrastructure. Digital asset infrastructure presents an even larger investment opportunity than digital assets themselves. We attribute this phenomenon to these encumbrances’ preference for rent seeking over subjecting themselves to the regulatory uncertainty and market volatility of digital assets. Hence, there is the issue about “skin in the game.” It solidifies the dominant powers, discourages DeFi to have healthy competition against legacy TradFi or CeFi, and exacerbates the gap between haves and have-nots. Without DeFi keeping CeFi intact, bureaucracy and barriers would be built and accumulated. This combined with the mentality of policymakers to use existing regulatory frameworks to guard against digital-asset risks is counterproductive.

Many do not seem to realize emerging threats against capitalism or dare to admit it. DeFi and de-dollarization movements are on the rise and reap benefits out of chaos. Foreign adversaries would like to see the U.S. engage in “unhealthy” competition to erode the country’s prominent market position. So, despite the quantum cat of digital assets appearing to be resurrected in a more tightly regulated form, its purpose may no longer serve the best interest of society. In our opinion, there are a few things regulators should do in view of this dilemma:

- Warn the public to “bear your own risks” and do not look to the government for a bailout.

- Curb chaotic / manipulative activities of users, consumers, and/or investors by the nature of transactions.

- Be vigilant in knowing who are consumers, investors and businesses that the government should step in to protect, and develop capabilities to discern and deal with insurgent/foreign adversaries.

Last but not least, the stage of digital assets development is like that of the warring states period before the Qin dynasty unified currencies with Ban Liang. For the mass adoption of digital assets to be beneficial to “equitable economic growth,” we must figure out a way to use digital assets to better delineate rights and obligations around the world to eliminate injustice. For additional thoughts, please see our Data Boiler comment letter to the U.S. Treasury.

Kelvin To (kelvin.to@databoiler.com) is a big data and fintech innovation expert

and founder and president of Data Boiler Technologies.

Topics: Digital Assets