Nature-related risks are on the rise. A recent PwC report found that more than half of global GDP, roughly USD 58 trillion, is materially exposed to nature-related risks — up from USD 44 trillion in 2020. To assist the many firms that are only just getting started, this article explains what nature is, how the economy both depends upon and impacts nature, and how these dependencies and impacts lead to nature-related risks.

1. What Is Nature?

Nature refers to the natural world and everything that occurs within it. This includes both the physical environment, such as rivers and mountains, and living organisms, including humans, animals, plants and microorganisms. Human society is typically regarded as highly interconnected with, but conceptually separate from, nature.

The Physical Environment

Nature can be broadly divided into four physical realms. These are land, freshwater, ocean and atmosphere. Figure 1 shows the overlaps between each realm, and of each realm with society.

Source: Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures

These realms can be subdivided into various biomes. For example, tropical forests, shrublands and deserts are land biomes, while rivers, lakes and wetlands are freshwater biomes. Some biomes are present in two or more realms, such as shoreline systems which involve both land and ocean.

Life on Earth

Biomes are inhabited by living organisms, each species of which has evolved according to its ecosystem. An ecosystem is a network of relationships between species, their physical environment, and other species.

For example, in a desert-based ecosystem, the extreme temperatures and dryness will determine which species can and cannot survive there. Similarly, a species that is outcompeted by another will be forced to adapt to a new role within the ecosystem, or else it will fail to survive.

Diversity within species, among species and of ecosystems is known as biodiversity. It is a key indicator of the resilience of an ecosystem to pressures from both natural processes (e.g., natural disasters) and human activity (e.g., pollution). Changes to the physical environment or to the interactions between species in an ecosystem will inevitably impact biodiversity.

Human Society

Nature underpins virtually all human activity and the two are inextricably linked (for more on this, listen to this GARP Climate Risk podcast with Simon Zadek).

It’s difficult to place a definite economic value on nature, as nature is a prerequisite for the existence of society, and therefore the economy. For example, without an atmosphere hospitable to human life — if it becomes too hot or too polluted — there wouldn’t be any economy to speak of.

The following section explains the predominant framework for thinking about the relationship between nature, society and the economy.

2. How Are Nature, Society, and the Economy Intertwined?

Understanding how society and the economy are dependent on nature is the first step toward understanding nature-related risks. The following concepts form the building blocks of the framework used to understand the relationship between society, the economy, and nature.

Environmental Assets, Natural Capital, and Ecosystem Services

Environmental assets are naturally occurring objects, processes or systems that are available to humankind. Examples of environmental assets include the air in the atmosphere, the soil created by land ecosystems, the rivers and lakes in freshwater ecosystems and the marine life in ocean ecosystems.

Natural capital simply refers to the global stock of all environmental assets. It can also refer to the sum of all environmental assets in a defined area (e.g., a region or city).

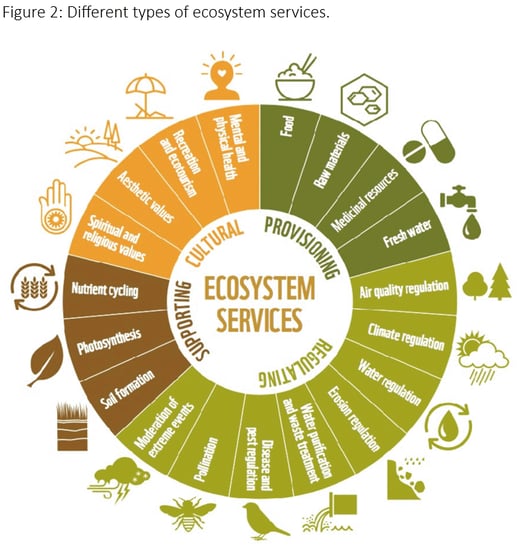

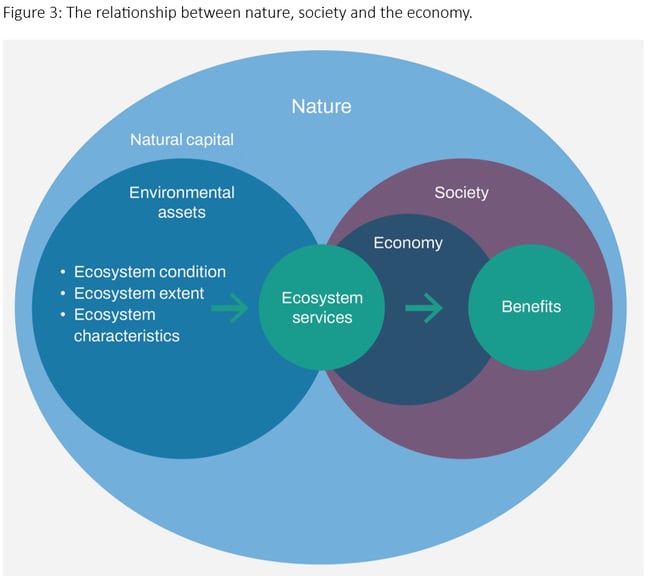

Whereas environmental assets and natural capital describe the different resources available in nature, ecosystem services refer to the flow of goods and services provided by natural capital, from which society derives various benefits. For example, the ability of soil to grow food is an ecosystem service, with food yielding obvious benefits to society. Figure 2 shows the various types of ecosystem services.

Source: World Wide Fund for Nature

Ecosystem services is a particularly important concept for understanding how society interacts with and benefits from the natural world. Figure 3 shows how these three concepts fit together, and how they are used to describe the relationship between nature and society.

Source: Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures

Dependencies and Impacts

All organizations — as well as individuals and society as a whole — are in some way reliant on the benefits provided by ecosystem services. To give a simple example, a traditional fruit-selling business relies on pollination, quality soil and regular rainfall to be able to grow and sell their produce.

However, these dependencies on nature are not always straightforward. Large, complex, real-economy companies, like electric vehicle manufacturers, may be dependent on the benefits from dozens of ecosystem services at different points in their supply chains.

Equally, business activities can also have impacts on nature, much in the same way that business can impact the climate. These impacts can be positive or negative.

Negative impacts reduce nature’s capacity to deliver the benefits from ecosystem services. For example, mining activities often produces toxic wastewater that can damage local ecosystems and may reduce that ecosystem’s ability to provide potable water for human consumption.

Positive impacts protect and restore nature’s capacity to deliver the benefits from ecosystem services. For example, farmers can develop hedgerows around agricultural fields that help protect and restore biodiversity, increasing that ecosystem’s resilience to negative change and protecting local soil quality.

Both dependencies and impacts on nature are the basis for nature-related risks at the societal, organizational and individual levels.

3. What Are Nature-Related Risks?

Nature-related risks are broadly defined by the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) as potential threats posed to an organization arising from its and wider society’s dependencies and impacts on nature. Like climate risks, nature-related risks are categorized into physical and transition risks.

However, for nature-related risks, individual companies also need to look at systemic risks. Systemic nature-related risks arise from the breakdown of the entire system, rather than the failure of individual parts. These risks are characterized by a cascade of events that combine in a chain reaction to produce large failures.

Physical Risks

Nature-related physical risks develop from the physical degradation of nature, for example through pollution or deforestation. Such changes can reduce the ability of environmental assets to provide the ecosystem services on which organizations and society depend.

Short-term, specific events that change the state of nature are known as acute physical risks. Long-term, gradual changes to the state of nature are known as chronic physical risks. Table 1 provides examples of nature-related physical risks on an organization.

Transition Risks

Nature-related transition risks arise from actions or processes undertaken by organizations or society to protect, restore and/or reduce negative impacts on nature. Like climate risk, a wide range of actions by a diverse set of actors can lead to nature-related transition risks. This includes:

- Policies intended to create positive or reduce negative impacts on natural capital, adopted by government or standard-setting bodies

- Technologies with fewer negative impacts on nature that outcompete old technologies, developed by private entities

- Changes in stakeholders’ perceptions of what is considered acceptable conduct (with regards to impacts on nature) at the societal, organizational and individual level

The main subcategories of nature-related transition risk are policy, legal, technology, reputational and market risks. Table 2 provides examples of nature-related transition risks on an organization.

Systemic Risks

The Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) identifies three key mechanisms by which systemic risks arise:

- Compounding effects, where the degradation or collapse of one ecosystem service triggers the degradation or collapse of others

- Cascading effects, where an initial physical or transition risk flows and amplifies through economic value chains, resulting in widespread loss and/or disruption

- Contagion effects, where the loss experienced by on one institution, market, sector or region induces changes in others

Systemic risks are also particularly relevant to policymakers and market regulators because of their potential to cause sudden and severe disruption to nature, society and the economy.

A Global Snapshot of Nature-Related Risks

Nature risks will affect all countries and companies to some extent; however, some industries are more exposed than others. In particular, according to a report by PwC, 100% of the economic value generated by the direct operations of the agriculture, forestry, fishing and aquaculture, food, beverages and tobacco, and construction industries are highly dependent on nature.

To illustrate the global extent of the risks from nature loss, Figure 4 maps out the global distribution of nature-related value at risk (i.e., the risk of loss of capital) from eight different key drivers of nature-related risks, as at 2023. It shows the comprehensive extent of the issues and indicates that many countries will have compounding affects from their exposure to many different drivers.

Source: Environmental Change Institute

Parting Thoughts

As the world wakes up to the stark realities of nature loss, our understanding of the extent of the global nature crisis seems to be outpacing our ability to counteract it — at least for the time being. It’s vital that risk professionals develop a robust understanding of these issues, to help firms and wider society take steps to address them.

Although this article has focused on the risks from nature loss, it’s also important to realise that nature presents a host of opportunities, which can create positive outcomes for nature and for organizations. This may be through avoiding, mitigating or managing those risks, or through the strategic transformation of business models, products and services, or investments that can halt or reverse the loss of nature.

To learn more about nature-related risks, read our white paper Biodiversity Loss: An Introduction for Risk Professionals. To better understand the relationship between climate change and nature-related risks, read our article Understanding How Biodiversity and Climate Change Are Interconnected.

Tom Strachan is an Assistant Vice President at the GARP Risk Institute, specializing in sustainability, climate risk, and nature risk.

Topics: Physical Risk, Transition Risk, Nature Risk Management