ESG stands for Environmental, Social and Governance. Collectively, these cover a broad range of non-financial issues that are increasingly regarded as sources of both financial risk and opportunity. In this article, we’ll delve into the origins and implications of ESG.

The Origins and Growth of ESG

Jo Paisley

The original use of the term ESG dates back to 2004, when the then-United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan invited 55 CEOs of major financial institutions to participate in an international project to integrate ESG into capital markets. That group produced a study in 2005 entitled ‘Who Cares Wins’, which set out the business case for embedding ESG factors into investment decisions, thereby improving the sustainability of markets and leading to better outcomes for society.

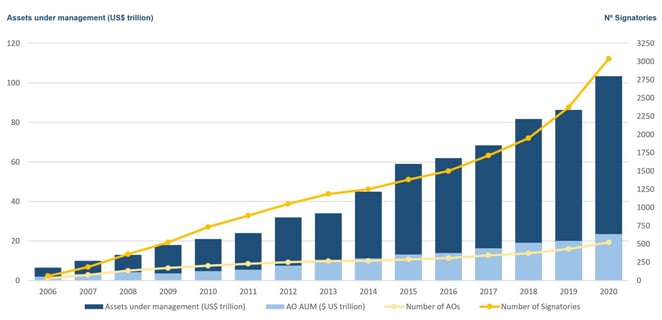

Since those early days, ESG investing has grown significantly. One indicator is the growth in the number of signatories and assets covered by the Principles for Responsible Investment Initiative (PRI) (Figure 1). Launched in 2006, signatories commit to incorporate ESG considerations into their businesses and investment processes.

Figure 1 PRI growth 2006 - 2020

Source: https://www.unpri.org/pri/about-the-pri

So What Counts as Being Part of ESG?

- The Environmental pillar refers to issues related to the natural world and includes aspects such as greenhouse gas (GHG) and non-GHG emissions; renewable/non-renewable energy generation and usage; biodiversity; land use; material resource use; water management and waste.

- The Social pillar refers to issues related to the lives of humans, such as human rights, modern slavery, child labor, working conditions, and employee relations.

- The Governance pillar captures the decision-making factors affecting a business, such as the gender and ethnic diversity of board composition, executive pay, bribery and corruption policies, political lobbying and donations, and tax strategy/transparency.

Where Does Climate Fit In?

The risks and opportunities from a changing climate most obviously fall in the environment pillar, although social (e.g. support for a ‘just’ transition to a low carbon economy) and governance issues (e.g. how well executive incentives align to climate outcomes) may also be relevant.

Investors’ Fiduciary Duties

An area of long-standing debate – particularly for asset managers – has been the extent to which taking account of ESG issues is compatible with their ‘fiduciary duty’, that is, the duty to work in the best interests of one’s clients. If fiduciary duty is interpreted as the maximization of shareholder value, it provides a reason to ignore broader environmental or social impacts, which might be costly to improve or rectify.

A UNEPFI sponsored report published in 2005 made it clear that there were no legal barriers in taking ESG considerations into account. Indeed, as they noted ‘…there is a body of credible evidence demonstrating that such considerations often have a role to play in the proper analysis of investment value’. While that report was helpful, it didn’t manage to end the debate and over the years this has been a constant refrain. Extensive work by the PRI and UNEP FI on this issue culminated in a 2015 report which stated that ‘Failing to consider long-term investment value drivers, which include environmental, social and governance issues, in investment practice is a failure of fiduciary duty.’ (Emphasis added).

Beyond Asset Management

ESG issues are not just pertinent to asset management and asset owners. Initiatives similar to the PRI have been launched more recently for Insurance and Banking. The spirit of all these initiatives is that ESG issues need to be considered as potential sources of risk as they can impact a firm at any point.

Indeed, today’s 24-hour news cycles and social media make the reputational impacts of ESG transgressions particularly difficult to manage.

ESG Fragmentation

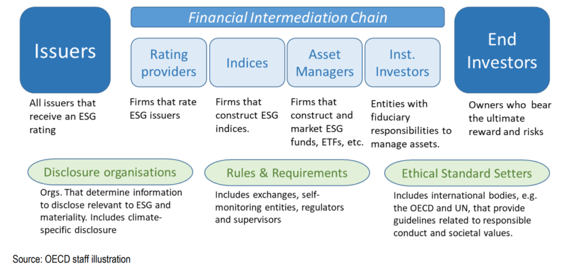

That said, judging which ESG issues are financially relevant and material for a particular firm can be difficult. Because ESG data and metrics have not traditionally been part of the mandatory financial reporting frameworks, a plethora of different approaches have grown up, making it challenging to compare across firms. And although there are efforts to introduce a globally more consistent approach to sustainability reporting, the landscape at the moment is confusing and fragmented. Indeed, as a 2020 OECD report noted, there is now an entire ESG financial ecosystem, from issuers to end investors, ratings providers, firms that construct ESG indices, standard setters, and disclosure organizations, and they could all be using different definitions and metrics (Figure 2).

Figure 2 ESG financial ecosystem

Source: https://www.oecd.org/finance/ESG-Investing-Practices-Progress-Challenges.pdf

Work is underway by the five leading framework and standard-setting organizations - CDP, Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB), Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) - to work towards a comprehensive corporate reporting system that includes both financial accounting and sustainability disclosures as outlined in their shared vision document in September 2020. But that will take time.

In the meanwhile, care is needed. Self-reported ESG metrics by firms will tend to put a gloss on issues of interest from a risk perspective. ESG ‘scores’ of companies from different providers are not well correlated, reflecting differences in proprietary methodologies, weighting schemes, and materiality assessments. Indeed, it is questionable if it even makes sense to weigh together the differing aspects of the three E, S, and G pillars to get to an aggregate score. (For an interesting discussion on this and other topics, listen to a recent GARP Climate risk podcast).

But even if you restrict yourself to just looking at the Environmental pillar, a recent OECD report highlights how little alignment there is between E scores from key rating providers (Bloomberg, MSCI, and Thomson Reuters) and climate risk indicators such as carbon dioxide emissions, and waste and water metrics. As they put it, “the E of ESG investing – in its current form – may not be the most effective tool for investors who wish to use it to align portfolios with climate transition to low-carbon economies”. Definitely food for thought for anyone wanting to use ESG scores as a shortcut to investing in climate-friendly investments.

Jo Paisley is the Co-President of the GARP Risk Institute and a leading expert on climate risk management.