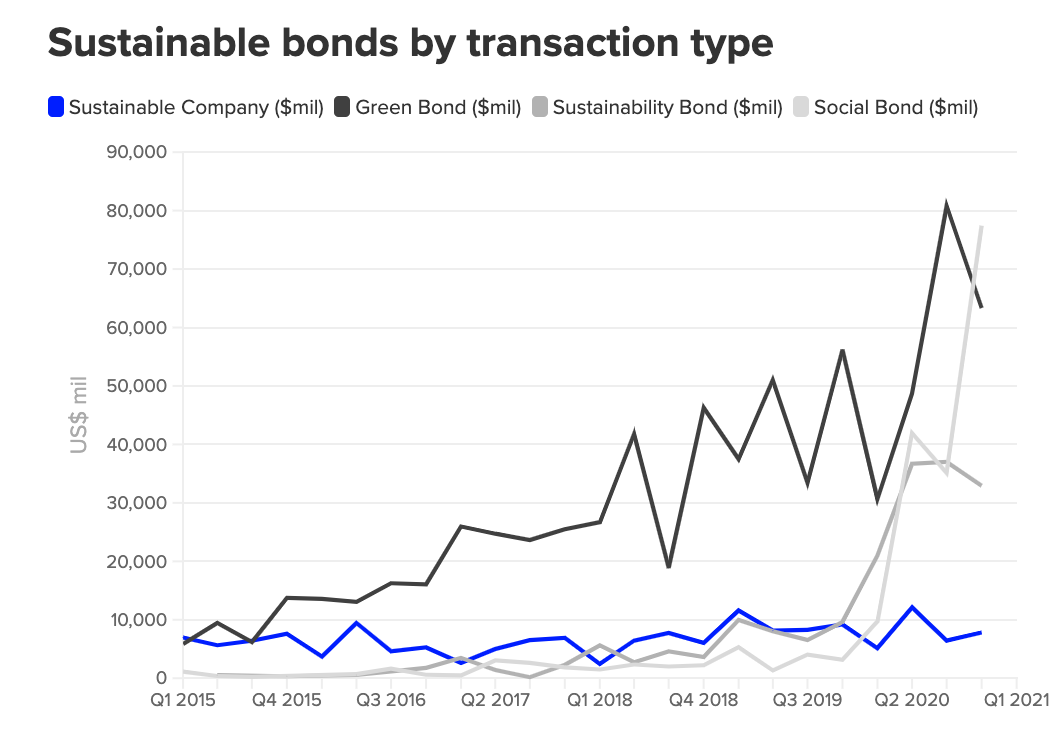

In 2020, approximately $500 billion of sustainable bonds were issued, a new annual record. There has been strong demand for these types of bonds; one recent example being the Italian government’s green bond issuance, which was oversubscribed by 10 times.

Sustainable bonds quarterly issuance is increasing rapidly

Source: https://www.refinitiv.com/perspectives/market-insights/sustainable-finance-surges-in-2020/

Green bonds

Since the first green bond was issued in 2007 by the European Investment Bank there has been an exponential increase in their issuance with more than $1 trillion now having been issued. Green bonds are used to finance or refinance projects that provide clear environmental benefits. Examples of projects that could be financed are:

- Renewable energy

- Energy efficiency such as building refurbishing

- Environmentally sustainable agriculture

- Natural resource such as sustainable water management

- Climate change mitigation or adaptation

An example of two large green bond issuances in 2020 came from Daimler and Volkswagen. EUR 1 billion and EUR 2 billion was raised, respectively, to support the companies’ transition to electric vehicles.

Social bonds

Just as green bonds have emerged as a response to rising awareness of global environmental and climate issues, social bonds have looked to address social challenges that threaten, hinder, or damage the well-being of society or a specific population. The volume of social bonds that were issued in 2020 increased nearly ten times from 2019 volumes, and are expected to continue to rise as bonds are issued by governments and companies to help with the post-COVID recovery. They could finance projects such as:

- Creating affordable basic infrastructure, e.g. clean drinking water, sanitation

- Access to health and education

- Providing sufficient food

For example, Ecuador has issued a social bond to finance affordable housing, and Russia’s Sovcombank has issued a bond to finance zero-installment loans to allow low-income individuals to purchase goods on credit.

Sustainability bonds

As projects that have environmental benefits often also have social benefits, and vice versa, a sustainability bond finances projects that aim to achieve both environmental and social benefits.

Large US financial institutions are examples of sustainability bond issuers; firms including JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, and Mastercard issued sustainability bonds in 2020 to finance areas such as renewable energy and affordable housing.

It’s not just a label

The labels green, social and sustainability can’t just be applied to bonds – they need to meet certain criteria. Firstly, the issuer needs to describe the process they used for evaluating and selecting the project. They also need to describe how they are going to manage the bond proceeds, and they need to regularly report on how the proceeds were used. Throughout the process there is an emphasis on communicating the environmental sustainability objective of the project that is being financed, and monitoring that the impact is being achieved. It is recommended, and is common practice, that the bond is externally reviewed, to verify that these steps are all followed.

Notwithstanding the rigor around issuing green, social and sustainability bonds, one critique is that – because they are structured around how the bond proceeds will be used – they are open to greenwashing and there are no penalties for not using the proceeds as specified. Another critique is that so-called brown companies can issue sustainable bonds to finance a small part of their operations, while not altering the bulk of their operations.

Sustainability linked bonds

A fourth type of bond, sustainability linked bonds (SLB), tries to overcome these problems. These are used for the issuer’s general financing needs but are linked to the issuer achieving predefined sustainability/environmental and/or social and/or governance (ESG) related goals. The bond’s financial and/or structural characteristics can vary depending upon whether KPI(s), that are material for the issuer, reach predetermined sustainability performance targets. For example, the coupon, maturity, or repayment amount can vary depending upon whether the issuer meets the goal it set itself to reduce its carbon emissions or to achieve an ESG related goal. Seaspan’s 2021 issue is a good example – if it fails to spend $200 million upgrading or acquiring ships to run on lower carbon emission fuels within 3 years, it will pay the bondholders an extra 50 basis points.

Other things you should be aware of

The International Capital Market Association (ICMA) is the secretariat for the framework and principles behind these bonds, and also has a database tracking the increasing number of bonds that have been issued. In fact, the bonds are becoming so prevalent that some stock exchanges have a section dedicated to these types of bonds.

Risk managers also need to be aware of the implications of the “greenium” for these bonds- due to the demand for green bonds, their yield is often lower than the yield on standard bonds from the same issuer. As one corporate entity is servicing both standard and sustainable bonds, this could mean that the credit risk of the issuer is being underpriced, as a trade-off for investing in the bonds. Not receiving adequate return for the credit risk could lead to problems in the future.

According to the Climate Bonds Initiative, social, green, and sustainability bonds are used by a range of issuers from sovereigns and development banks to corporates and financial institutions. And they are used across a variety of industries. Being more aware of the characteristics of these bonds, that are being generated in response to social demands and climate change, will therefore help risk managers understand what is driving the increase in volumes and the risk-return trade-offs.

Maxine Nelson, Senior Vice President, GARP Risk Institute, is a leader in risk, capital and regulation. In her career, she has held several senior roles where she was responsible for global capital planning and risk modeling at banks. She also previously worked at a UK regulator, where she was responsible for counterparty credit risk during the last financial crisis.