Policy makers across multiple jurisdictions have been developing taxonomies, which aim to define what is “green”. But how do they fit in risk management? And what role do they play in solving climate change? This article explores what taxonomies are, what they are not, and their role in financial markets and the climate transition, in part drawing on conversations in GARP’s Climate Risk podcast series.

What is a ‘green’ taxonomy?

A green taxonomy is a comprehensive classification scheme, which sets out the definitions and criteria that an activity must meet in order to be classified as ‘green’ or environmentally sustainable.

Why is it needed? As we transition to a net-zero economy a key challenge is to encourage sufficient investment in areas such as climate change mitigation and adaptation. But if everyone comes up with their own definition of ‘green’, there’s no guarantee that investments will be deployed appropriately or at sufficient scale. The ambiguity would also provide fertile ground for ‘greenwashing’, wasting opportunities to limit the effects of climate change. By setting out common definitions, a green taxonomy can help overcome these problems.

CEO of the Climate Bond Initiative, Sean Kidney, gave us insight into the historical development of green taxonomies. An early example of a green taxonomy was developed back in 2012, established to support the development of climate bonds, the proceeds of which must be used in ‘green’ projects. This became a model for the Chinese taxonomy, which has since been followed by the European taxonomy. Many other nations are developing their own green taxonomies, including recent publications in Singapore and Columbia.

One dimension that serves to differentiate taxonomies from one another is differences in scope. For example, the OECD notes that the EU Taxonomy on Sustainable Finance is unique in having a broader set of environmental goals, as well as social and governance objectives. It aims to create a common, science-based, language to overcome the problems which were arising with each Member State setting its own standards and classification systems for sustainability. As it is arguably the most ambitious taxonomy in the world, it’s worth exploring in a little more detail.

Chief Sustainable Finance Advisor at the European Investment Bank, Eila Kreivi, provided more detail about the development of the EU Taxonomy. Work began in 2018, focusing initially on climate change mitigation and adaptation for the areas of the economy that would have the most impact on the climate. As she explained, the taxonomy is quite simply a “big dictionary”, which establishes a list of environmentally sustainable activities.

Under the EU Taxonomy, a ‘sustainable’ activity must meet three criteria:

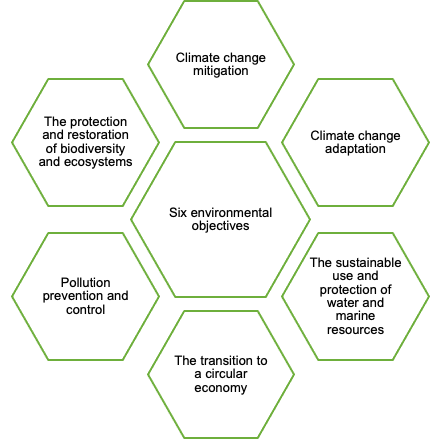

- First, it must substantially contribute to one of the six environmental objectives (Figure 1).

- Second, it must do ‘no significant harm’ to the other five objectives (DNSH).

- Third, it must comply with the minimum social and governance standards set out by the EU, UN and OECD.

Figure 1

Kreivi explained the nature of the granular work involved to create the dictionary, with it standing at some 800 pages so far, and set to increase in length. As of 1 January 2022, the Taxonomy Regulation covers just the two climate change objectives (namely, adaptation and mitigation), with work underway to extend it to the other environmental objectives (due to be published during 2022). Although it may seem long and complex, it’s not designed to be read from start to finish - its utility is in providing a comprehensive list of what counts as ‘green’ or ‘sustainable.’

The EU taxonomy is also more complex than others with the inclusion of the ‘DNSH’ criteria. Here various ‘Technical Screening Criteria’ (TSC) define the specific requirements and thresholds for an activity to be considered as ‘significantly contributing’ to a sustainability objective or for determining whether it does not significantly harm any of the other objectives.

The taxonomy also defines ‘transition’ activities (those that contribute to the transition but aren’t themselves close to net-zero) and ‘enabling’ activities (those which directly enable other activities to make a substantial contribution to one or more of the six objectives).

How do these taxonomies fit into risk management?

In many ways, green taxonomies are not directly informative about risks. The EU taxonomy, for example, specifies the destination: that is, what counts as ‘green’. As Kreivi noted, from a risk management perspective it might be more helpful to understand how much of firms’ revenue or business activities are involved in ‘brown’ or ‘significantly harmful activities’. The taxonomy is also silent on the financial costs or risks involved with transitioning to green.

The taxonomy was designed to be a tool to be used by investors who wish to make claims about how ‘green’ their investments are. There are, however, sometimes differences of view of what should be counted as ‘green’. This is seen particularly clearly in a recent debate over whether nuclear energy and fossil gas should be treated as ‘transitional’ green activities, within the taxonomy. Analysis by think tank Influence Map indicated intense lobbying efforts by industry for gas to be included. Commentators have been quick to argue against this on the basis that these fuels do not meet the agreed ‘green’ criteria.

This shows the difficulty and political nature of implementing a taxonomy.1 Kreivi also noted that this incident shows how some stakeholders have missed the point of the taxonomy, with some believing that if an activity is not classed as ‘green’ then it will be treated as a pariah. Of course, the desire to classify an activity as ‘green’ irrespective of its actual environmental footprint risks undermining the taxonomy’s usefulness, for investment purposes or risk management.

On the other hand, the development of taxonomies has brought benefits, which are useful for risk management. According to Kidney, they have established the idea that science – rather than politics – should drive what we need to do, even if on occasion that assumption gets tested. He also thought that the taxonomies provide ‘signposting’, for risk professionals, of things that are less likely to be negatively impacted by policy going forward. The EU taxonomy could also serve as a tool for the planning and reporting of transition pathways, as a recent UNEP FI report outlines. If this is the case, then the taxonomy will only grow in significance.

An alternative, but arguably complementary, approach is to employ a taxonomy of climate risks which will affect firms, such as that published by Imperial College Business School in 2022. This covers the following broad categories of risks:

- Physical risks, acute and chronic;

- Transition risks related to adaptation;

- Transition risks related to mitigation; and

- Natural capital risks.

The first three categories are familiar, although it is interesting that transition risks have been sub-divided into those arising from adaptation and those from mitigation, allowing greater granularity in the classification of risks. The fourth category, natural capital risks, is novel. These are defined as ‘specific risks to asset values, profitability, cash flows, or margins stemming from natural events that are potentially being accelerated as a result of some form of natural capital depletion or disruption’. For example, this part of the taxonomy distinguishes between:

- subsidy regime changes (such as agricultural or fossil fuel subsidy loss);

- depletion risks (including water stress);

- boundary condition risks (such as biodiversity loss); and

- geopolitical event risks (such as migration caused by environmental impacts).

This links to points that we have written about previously concerning the scope of risks – it is unlikely that we can limit ourselves to examining just those arising from climate change. We will need to widen the net to other broader environmental concerns.

Do taxonomies help address climate change?

There is a huge amount of supervisory and regulatory activity in the areas of climate, environment and sustainable finance. But the million-dollar question is how much all these regulations will help us address the climate crisis?

Founder of the Carbon Tracker Initiative, Mark Campanale believes that the focus on taxonomies (and reporting) is the wrong approach for tackling climate change. For a start, these taxonomies are only relevant to those who wish to make claims about being green; they do nothing to stop companies emitting greenhouse gases.

Campanale argues we need to re-cast climate change as a supply-side issue and make more fundamental changes to financial markets. For example, one idea is to change the admissions process for debt and equity markets, demanding granular disclosures about the risks of the business, before finance is raised. No need for a taxonomy to define what is green – you can let the market decide which ones to fund on the basis of the information provided. He worries that initiatives such as the various taxonomies and reporting frameworks (such as TCFD) are a costly distraction, diverting resources away from taking the kind of radical actions needed to reduce greenhouse emissions meaningfully. (See their report Flying Blind: The Glaring Absence of Climate Risks in Financial Reporting for a critique of climate-related disclosures.)

In sum, green taxonomies have their uses, their limitations and are open to abuse and misinterpretation. Risk professionals would do well to delve into this increasingly complex and fast-moving landscape, as they are not going away any time soon.

For further insights into this important topic, you can hear the full interviews with Sean Kidney, Eila Kreivi and Mark Campanale via GARP’s Climate Risk Podcast.

1There is work to develop a common ground taxonomy, which will look at areas of overlaps across different nations’ taxonomies, aiming to rationalize and improve interoperability between each region.

Topics: Green Finance & Sustainable Business, Climate Risk Management