Global regulatory and market trends are pressuring firms to disclose their impacts on climate change through a process known as greenhouse gas (GHG) accounting. Combined with the proliferation of voluntary and mandatory GHG reporting programs, these trends have heightened the urgency for financial institutions and their risk managers to gain a better grasp of this process.

What Is GHG Accounting and What Does It Achieve?

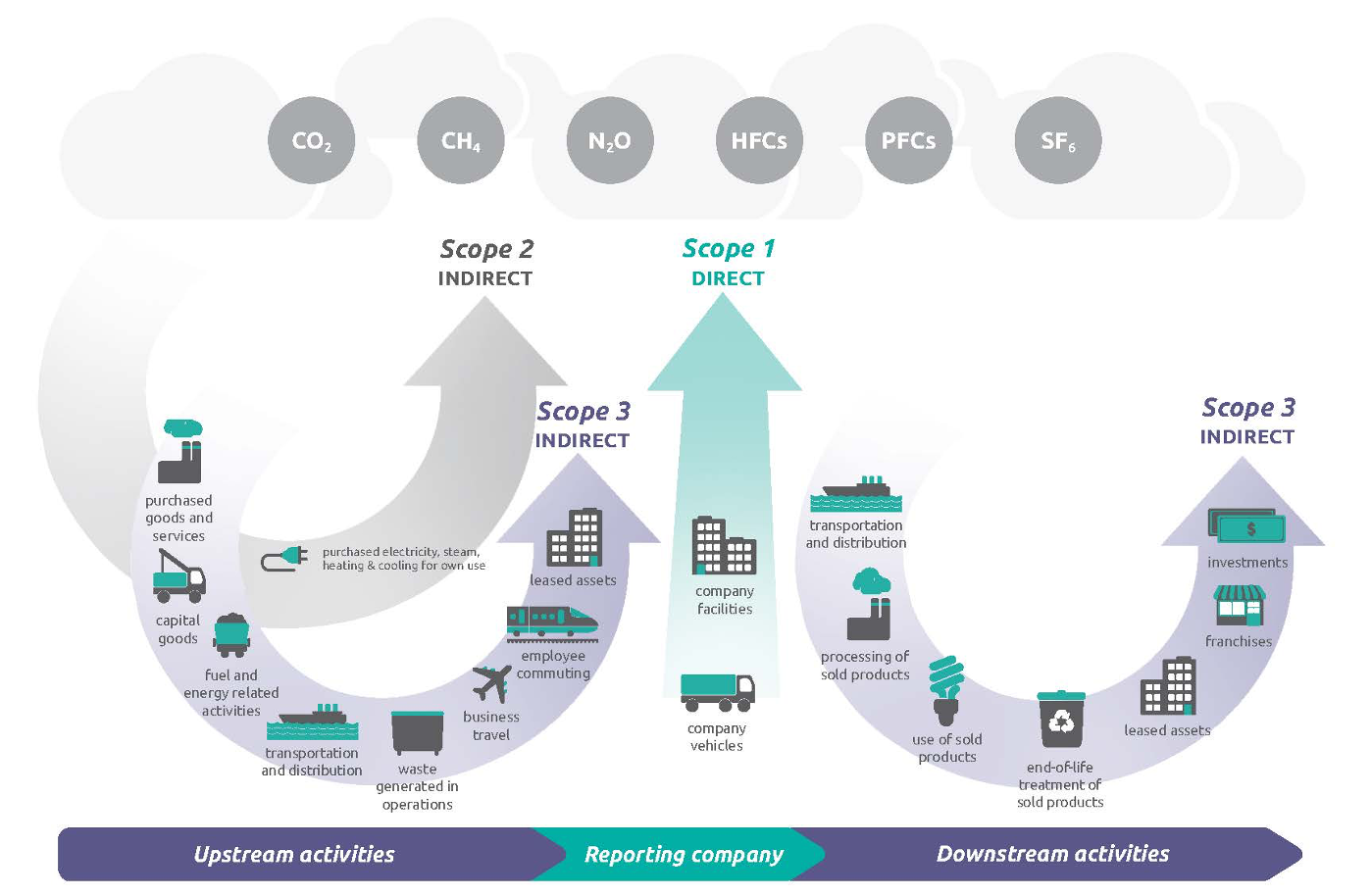

GHG accounting is the process of calculating, recording, and reporting the emissions that occur throughout an organization’s value chain. The term is preferred over "carbon footprinting," as non-carbonic GHGs, such as nitrous oxide, should also be considered.

GHG accounting is used by firms to measure the emissions associated with their business activities. This includes both emissions that occur from sources owned or controlled by the firm – like vehicles or on-site fuel combustion – and from sources that are not – such as purchased electricity or business air travel.

Risk and finance professionals should be aware of GHG accounting for several reasons:

- it is the standardized global approach for how firms worldwide track and report their emissions over time;

- it allows businesses and stakeholders to make informed decisions about their risks and opportunities from climate change;

- it is essential for the functioning of many market-based and regulatory mechanisms; and

- it is a crucial first step in mitigating GHG emissions, which is essential to the long-term stability of our environment and economy.

How Does GHG Accounting Work?

Although multiple GHG accounting standards exist today, the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Protocol is the most widely used. Their framework for GHG accounting, released in 2001, has been adopted by governments and private organizations worldwide. There are four main steps to the GHG accounting processes:

|

Step |

Organization’s Actions |

|

1. Setting boundaries |

Select which activities’ emissions to measure, according to the legal structure and desired outcomes. |

|

2. Collecting data |

Gather key information relating to the chosen activities: e.g., how much electricity was consumed by the firm in the last 12 months? |

|

3. Calculating emissions |

Calculate the emissions based on best available information: e.g., the emissions associated with delivering one unit of sold product. |

|

4. Verification and reporting |

Verify and/or report the calculations. These steps may be done internally or externally. |

Adapted from the GHG Protocol’s Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard (2001)

These steps are completed through a document known as a GHG inventory. As the name suggests, the GHG inventory is where an organization’s emissions are identified, sorted, and tracked over time (like a traditional accounting ledger). A large firm could be tracking thousands of different emissions-producing activities at any given time, so a well-kept GHG inventory is essential for organizing activities and understanding the composition of the total GHG footprint.

The main way of organizing the activities is to categorize them according to where emissions are produced in an organization’s operations and value chain. These categories are referred to as scopes, and are defined in the table below:

|

Category |

Definition |

Example activities |

|

Scope 1 |

Direct GHG emissions that occur from sources that are owned or controlled by the organization. |

|

|

Scope 2 |

Indirect GHG emissions from the generation of purchased electricity consumed by the organization. |

|

|

Scope 3 |

Indirect GHG emissions that are the consequence of the activities of the organization, but occur from sources not owned or controlled by the organization. |

|

Adapted from the GHG Protocol Initiative’s Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard (2001)

According to the GHG Protocol, organizations should always measure all Scope 1 and 2 activities when developing a GHG inventory. Scope 3 is described as an “optional category” and an opportunity for organizations “to focus on one or two major GHG-generating activities” that fall outside of their Scope 1 and 2 emissions. The reason for this – despite Scope 3 being by far the largest category of emission for most firms – is that one organization’s Scope 3 emissions are often another organization’s Scope 1 emissions.

For example, a consulting firm might count emissions from business air travel within their Scope 3, while the airline counts those same emissions within their Scope 1. This is referred to as double-counting and it becomes problematic when multiple parties claim the same reduction in emissions. Nonetheless, measuring and understanding Scope 3 emissions is still useful for firms in other ways – for example, when managing transition risks from climate change.

It can be helpful to think of Scope 3 emissions as coming from either upstream or downstream activities. As shown in the diagram below, upstream emissions occur from purchased or acquired goods and services, while downstream emissions occur from sold goods or services rendered.

From Greenhouse Gas Protocol's Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Standard (2011)

When Might Firms Use GHG Accounting?

Meeting Regulatory Requirements

Some firms are legally obliged to measure and disclose their emissions externally using GHG accounting.

UK incorporated firms that are large (250+ employees, annual turnover >£36m, and/or annual balance sheet >£18m) and listed on the London, New York, and NASDAQ stock exchanges – or in European Economic Area markets – are currently required to disclose their annual Scope 1 and 2 emissions. Moreover, they must disclose other environmental metrics under the Streamlined Energy and Carbon Reporting (SECR) regulations.

Large EU public-interest firms with more than 500 employees – such as firms listed with an EU regulated market, credit institutions, insurers, and other designated firms – are currently required to disclose their annual emissions, as well as other social and environmental metrics under the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD). The upcoming Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) – the first reports for which will be released in 2025 – will expand upon the NFRD to require more sustainability-related disclosures and will eventually include more firms of all sizes.

In the U.S., firms are required by federal law to disclose their annual GHG emissions only if their facilities potentially emit more than 25,000 metric tons CO2 equivalent per year (excluding Scope 3). In March 2022, the SEC proposed new rules that would require all public firms to disclose their Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions.

Transition Risk Management

Transition risk refers to the potential for negative consequences from society’s adjustments to a lower emissions or net-zero economy. In general, the more emissions-intensive a firm, activity, or asset is, the more exposed and vulnerable it is to transition risks. Firms that use GHG accounting to understand the sources of emissions in their value chains may be able to reduce their exposure and vulnerability to transition risks.

Imagine a firm conducts a GHG inventory and finds that a single supplier in its value chain accounts for over 70% of its total emissions (including Scope 3). If the government were to introduce a carbon tax, this could significantly increase the cost of doing business with that supplier. In this way, GHG accounting can detect markers of transition risk and prompt firms to take pre-emptive action – to explore, for example, less emissions-intensive suppliers or alternative ways of doing business.

Moreover, firms that can distance themselves from business practices or partners regarded as unsustainable (e.g., practices that are deemed to have high impacts on climate change and/or the environment) may also be able to reduce their exposure to reputational risks from the transition to net-zero. Firms can further reduce this risk type by voluntarily reporting the results of their GHG inventory, demonstrating transparency and accountability.

Harnessing Transition-Related Opportunities

GHG accounting is also a useful tool for identifying and pursuing transition-related opportunities, especially for firms in transitioning economies.

Firms that pursue the highest levels of GHG accountability can obtain the endorsement of independent standard-setters, which may lead to competitive advantages. Cross-sectoral organizations such as B-Corp offer certification to firms with best-in-class sustainability practices. A 2022 Deloitte study on sustainability found that 49% of UK consumers are willing to pay more for sustainable brands, with 35% being more likely to trust firms with more transparent and socially and environmentally responsible supply chains.

Furthermore, sustainable business practices have become an important factor in attracting employees and investment. A 2021 study found that 53% of UK employees consider sustainability a key factor when selecting an employer. Similarly, a 2020 global study found that 43% of institutional investors regularly prioritize environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors in their investment decision-making.

Participation in Carbon Markets

Carbon markets are trading systems that allow participants to buy and sell GHG credits (i.e., the right to pollute). There are currently three main carbon markets: compliance, international, and voluntary.

Compliance carbon markets are based on emission trading schemes (also known as cap and trade) where authorities put a limit on the amount certain companies can emit; if they exceed those limits, they can buy permits from other companies. Globally, $851 billion worth of emissions permits were traded through compliance markets in 2021. GHG accounting plays a vital role in ensuring the integrity of this market and allowing regulated companies to fairly trade their emissions.

The international and voluntary carbon markets are much smaller in comparison. The international carbon market is based on the Clean Development Mechanism of the Kyoto Protocol, which allows developing countries to sell GHG credits from emissions-reduction projects to developed countries. In the voluntary carbon market – which is largely self-regulated – GHG credits are sold by private organizations and may be purchased by any private entity or individual.

Although each market has a different set of rules, GHG accounting is essential for participants in all three markets to ensure the validity of GHG credits and to allow firms to quantify their demand for GHG credits.

Parting Thoughts

GHG accounting is a powerful tool that has a variety of uses for both firms and regulators. Global regulatory and market trends are steadily reinforcing the need for risk and finance professionals to understand, and in some cases practice, GHG accounting.

Tom Strachan is a climate risk and sustainable finance analyst at the GARP Risk Institute.

GARP’s Sustainability and Climate Risk (SCR) Certificate provides the foundation needed to tackle climate related risks and help prepare for future regulatory climate mandates.

Topics: Transition Risk, Green Finance & Sustainable Business