How can you judge the reasonableness of modelled scenario analysis outputs if the scenario is one that you’ve never experienced? This is a dilemma that has faced many risk professionals involved in the raft of new supervisory climate stress tests. This article provides insights into a benchmarking exercise that GARP undertook to support banks in the UK’s recent climate scenario analysis exercise.

Difficulties sense checking climate scenario analysis results

Many supervisory authorities have announced their intention to undertake some sort of supervisory climate stress testing exercise for the banks in their respective jurisdictions. These exercises pose many practical difficulties, for example:

- robustly mapping between climate variables and the macroeconomic ones that banks traditionally use for modelling future projections is challenging;

- the scenarios themselves tend to be over longer time horizons than those used in traditional stress testing exercises, which raises additional modelling challenges; and

- there is a lack of historic data to backtest the outputs.

This last point is particularly difficult to overcome. Robust model risk management requires that new models should be backtested using historic data, so that their accuracy can be evaluated. This process helps to reassure the users of scenario analysis, senior management and regulators that the results are meaningful.

However, for climate scenario analysis, the data that can be used is very limited or non-existent. This is partly because the future risks from transition and physical risk are expected to be larger, more widespread, and more diverse than other, prior, structural changes. But also, there’s the practical point that collecting and processing the relevant information simply has not been a priority for firms up to now. Although it may be possible to use proxies, there is still likely to be significant uncertainty over how to judge the ‘reasonableness’ of the results and whether, for example, overlays need to be applied.

One way around these shortcomings is to use benchmarking across a number of different firms. Comparing your own modelled results with those at other institutions, can help overcome the challenges posed by limited historic data.

Care is needed when constructing such an exercise to ensure that confidentiality is maintained and that any exercise does not breach competition law. However, GARP has extensive experience of undertaking benchmarking exercises with financial institutions, which we used to shape a benchmarking exercise for banks involved in UK’s climate scenario analysis exercise. So what was the exercise all about?

Peer benchmarking a climate scenario exercise

The Bank of England’s Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario (CBES) exercise was launched in June 2021, having been delayed a year because of the COVID pandemic, and the results have just been published. The CBES exercise covered major UK banks and insurance companies.

The focus of the exercise was to examine the vulnerability of the participating firms’ current business models to future climate-policy pathways and varying degrees of global warming. To do this, the scenarios were applied to the end-2020 balance sheets, which acted as a proxy for their current business model.

Three scenarios were provided: two focused on the transition to net zero greenhouse gas emissions but differed according to how orderly the pathway was. The other scenario allowed no additional climate policy action, resulting in rising physical risks throughout.

The Bank of England (BoE) was explicit that it intended the CBES to be a ‘learning exercise’, recognizing that modelling climate-related risks is in its infancy and that climate risk assessment techniques are still developing. In the spirit of supporting learning, throughout 2021, GARP hosted a regular roundtable for some of the modellers at the various banks involved in the CBES exercise. The discussions were helpful in identifying areas that were proving particularly challenging. With the banks heavily focused on credit risk in the banking book, especially of their large corporate counterparties, this was a natural place to prioritise a benchmarking exercise.

Developing the benchmark

Over the course of a few months, we designed a series of benchmarking templates which the banks filled in and submitted to GARP. All the submissions were confidential. No bank exposed its data to the other participating banks nor were they able to view individual data of the other banks; only GARP had access to the full set of data submitted. The group also agreed to keep all results confidential to the participants.

We chose to focus on modelling transition risk in the disorderly transition risk scenario, which was going to be the more severe of the two transition risk scenarios. The benchmarking was set up to assess the reasonableness of probability of default (PD) migrations across corporates in different sectors, and with different credit ratings (see Table 1).

Table 1: Parameters used for climate PD benchmarking

| Scenario | NGFS Disorderly Delayed 2oC with limited Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR)* |

| Sectors | Oil and gas European utilities – a portfolio of 10 companies Commercial real estate Chemical companies Mining Aviation Automotive |

| Credit Rating Buckets | AAA/AA/A BBB BB B |

| Time horizon | Five-yearly intervals from 2020 to 2050 |

| Counterparty Information | Number Average size |

* Some firms used a similar scenario, rather than this exact scenario

In the GARP exercise, banks modelled current and projected PDs for the counterparties within the various corporate sectors shown in Table 1, split by credit rating at December 2020, and then submitted these results at five-yearly intervals from 2020 to 2050.

Clearly the sectors cover a wide range of different sub-sectors. For example, the PD of a coal mining company will evolve very differently to a company focused on mining lithium. Nevertheless, by grouping the companies by their current PD, we could look broadly at how creditworthiness evolved.

Banks also provided details on the number and average size of those counterparties, as well as high-level information on the modelling approach that they used. This information provided helpful insights into other potential drivers of variability in the submitted PDs, improving our interpretation of the modelled results.

Consistent with the BoE’s prescribed methodology for the CBES exercise, the exposure of each counterparty was held constant throughout the scenario. If a counterparty defaulted it stayed in the population, with a PD of 100%.

These guidelines might seem somewhat counterintuitive. However, this simplifying assumption of a fixed balance sheet was akin to examining how a bank’s current business model (as proxied by their opening balance sheet) could perform when transition and physical risks increase. The CBES also explored how firms intend to adapt their business models and management actions they might take.

Quantitative outputs

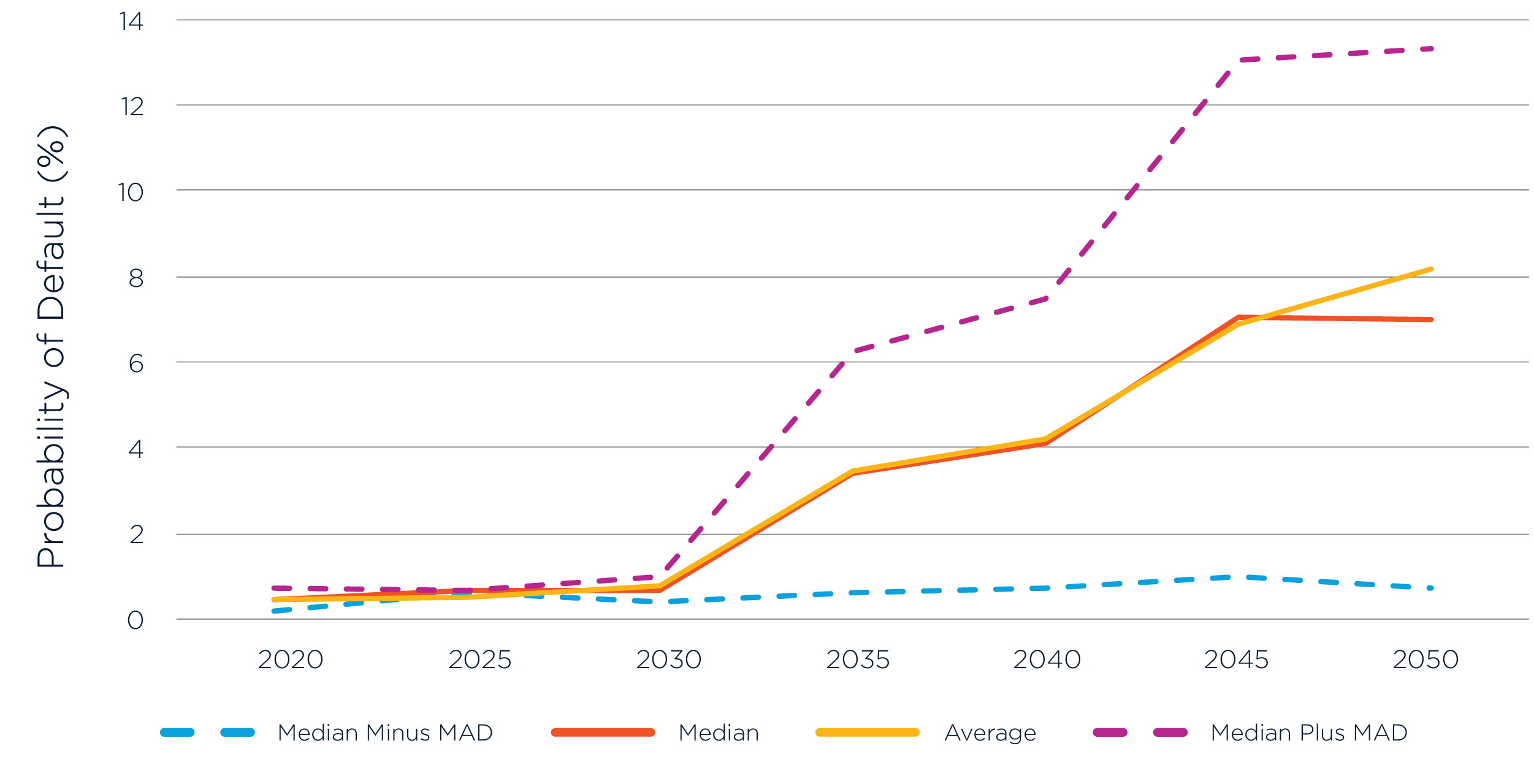

Figure 1 gives an example of the type of information provided back to participating banks- including the mean, median, and median absolute deviation (MAD)*. This aggregated information, on the evolution of PDs over 5-yearly intervals from 2020 to 2050, allowed banks to see where their calculated PDs sat on the distribution. It also illustrated the spread of results, which differed across the sectors examined.

*Median absolute deviation of a data set is the median of the absolute values of the difference between each data point and the median of the data set. That is, for a dataset X1, X2… Xn, MAD = median (|Xi-median (X)|. It was used as the measure of dispersion because it is more robust than standard deviation for small samples with potential outliers, which this benchmarking had.

Figure 1: PD of one rating bucket, for one sector, over time

Key learnings

From this pilot exercise, participating firms learned a great deal. For example, one interesting finding was the wide dispersion of results. This is in keeping with the findings from the CBES and is perhaps not surprising given how new this is to financial firms. Indeed, the BoE set the CBES up to enable participants to take a range of approaches, to improve their thinking and build capability.

A further finding from the GARP exercise included the importance of different calculation assumptions. For example, firms realised the critical importance of assumptions made about the ability of the counterparties to adapt their business models. It was also important to agree if defaulted counterparties (that is, those with PDs of 100%) should be included, or excluded, in the sample as this was a big driver of the variability across results. Another issue discussed was whether the banks should incorporate economic effects beyond those directly caused by climate impacts.

Other issues were also pertinent. Should the PDs of counterparties be calculated at group or entity level? Were emissions available at group or obligor level, and what was the best way to proxy them when they weren’t available at the level they were needed at? Various other modelling questions arose, such as the best way to incorporate the impact of climate change – for example, through changes in price, volume, unit cost, capex, or a carbon price.

Most importantly, and mindful of a number of caveats on the extent to which the exercise could provide robust insights, the exercise provided participants with insights on whether their calculated PD changes were in the same ballpark as those of other firms. It also gave them information about differences in approach which could help explain why there might be variations in the evolution of modelled PDs. It thereby not only helped give assurance about the reasonableness of the calculations but also provided valuable information to improve the calculations in this challenging and emerging field.

Maxine Nelson, Senior Vice President, GARP Risk Institute, currently focusses on climate risk management. She has extensive experience in risk, capital and regulation gained from a wide variety of roles across firms including Head of Wholesale Credit Analytics at HSBC. She also worked at the U.K. Financial Services Authority, where she was responsible for counterparty credit risk during the last financial crisis.

Topics: Physical Risk, Transition Risk, Climate Risk Management