At a time of growing concern about climate change and sustainability, pollution attributable to production and accumulation of plastics is raising questions relating to the extent of the long-term environmental damage, who will be held accountable for the costs, and how the risks might be managed or transferred.

At least for a few years, industry has stayed ahead of the threat with, for example, innovative packaging such as Tetra Pak milk and food cartons, 100% sourced from plant materials. NestlÉ, the world's biggest packaged foods company, has committed to transitioning away from plastics and towards paper.

Dell's computer packaging is gradually becoming biodegradable. Dasani “plastic” water bottles have up to 30% plant-based ingredients.

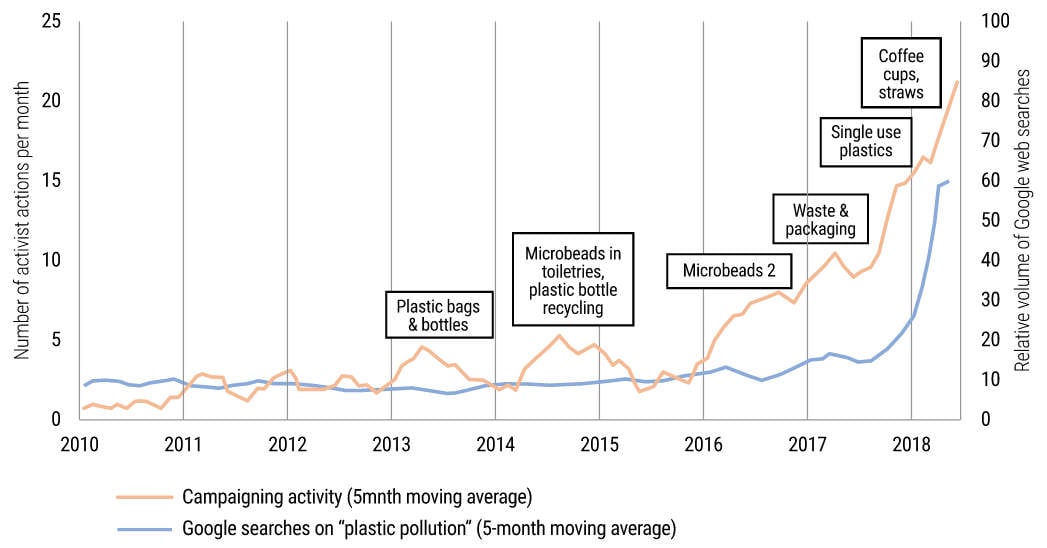

The momentum in that direction has been building, albeit slowly, due to public opposition to plastic waste, litigation initiated by advocacy groups, and climate-change awareness.

And while industrial firms tout environment-friendly responses, products that pose a risk to clean air, water, and communities in general have emerged as an opportunity for insurance underwriters.

Environmental Vulnerability

The environmental movement that arose in the 1960s and culminated in the first Earth Day in 1970 raised questions of liability, and as early as 1973, insurers began incorporating exclusion clauses in their policies. By 1978, American International Group (AIG) was offering environmental impairment liability insurance.

Environmental insurance has since proliferated, along with public sentiment - if not empirical evidence and the occasional catastrophic event - that placed substantial blame for adverse impact on corporations.

Single-use plastic containers are now a leading pollution source. Discarded plastics endanger oceanic ecosystems. This has given rise to bioplastics, scientific efforts to incorporate organic ingredients that can degrade as compost.

But the clock on damages can't be turned back.

Going to Court

In February, Earth Island Institute in the San Francisco Bay Area sued 10 companies, including Coca-Cola, NestlÉ, PepsiCo and Procter & Gamble, in what it termed “the first lawsuit filed in the United States that seeks to hold major food, beverage, and consumer goods companies accountable for plastic pollution” - a cohort that the non-profit dubs “big plastic.”

“This is the first of what I believe will be a wave of lawsuits seeking to hold the plastics industry accountable for the unprecedented mess in our oceans,” said institute board president Josh Floum. “These plastics peddlers knew that our nation's disposal and recycling capabilities would be overrun, and their products would end up polluting our waterways.”

Elsewhere, San Antonio Bay Estuary Waterkeeper successfully sued a Texas company, Formosa Plastics Corp., alleging microfine plastic pellets were discharged into waterways in violation of its wastewater permit.

Charleston Riverkeeper in South Carolina, under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act and Clean Water Act, sued Frontier Logistics, claiming that its discharged pellets were an “imminent and substantial endangerment to health or the environment.”

Even the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was targeted when the Center for Biological Diversity, Surfrider Foundation and Sustainable Coastlines Hawaii accused the regulator of approving impaired waters without accounting for plastic pollution. The advocacy groups won, and the EPA withdrew its approval of impaired waters “specifically with respect to the consideration of plastics.”

Full-On War?

In an April Bloomberg Law article, four King & Spalding attorneys considered whether the recent litigation signals “the beginning of full-on war on plastics. No doubt the number of plastics lawsuits filed just this year alone signals a discernible litigation trend. From certain perspectives, many of these lawsuits can be viewed as straightforward environmental lawsuits aimed at specific plants and raising specific regulatory issues."

Four lawyers from the Crowell & Moring firm see the trend underlining plastics' place in the environmental impact equation. “The topic of marine litter more broadly is also receiving increased attention, both internationally, with actions by the European Union and Canada to ban single-use plastics and passage of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada trade agreement, and domestically with the enactment of the Save Our Seas Act,” they wrote.

“Some companies have formed an alliance to proactively develop solutions for reducing plastic waste and improving recycling and waste collection infrastructure in Asia and other parts of the world,” their February article continued. “And on February 11, 2020, Senators Tom Udall and Jeff Merkley, along with Representatives Alan Lowenthal and Katherine Clark, introduced the Break Free from Plastic Pollution Act of 2020, aimed at increasing recycling rates and reducing new plastics production.”

The Crowell & Moring authors concluded, “In the absence of comprehensive federal or international action to address marine debris and plastic pollution, NGOs can be expected to continue to use litigation under existing laws and novel legal arguments to pressure policy makers to act. Through a combination of litigation, legislation, and company-led efforts, the next few years appear poised to change the life cycle of plastic.”

“All Over the Place”

Plastics' problems are compounded by research finding microfibers to be airborne and ubiquitous, an invisible menace to clean air.

“It's really unnerving to think about it,” in the words of Janice Brahney, a Utah State University scientist and co-author of a recent study of these byproducts, speaking to the New York Times.

“Because plastics are persistent,” the study explains, “they fragment into pieces that are susceptible to wind entrainment. Using high-resolution spatial and temporal data, we tested whether plastics deposited in wet versus dry conditions have distinct atmospheric life histories. Further, we report on the rates and sources of deposition to remote U.S. conservation areas. We show that urban centers and resuspension from soils or water are principal sources for wet-deposited plastics.

“By contrast,” it continued, “plastics deposited under dry conditions were smaller in size, and the rates of deposition were related to indices that suggest longer-range or global transport. Deposition rates averaged 132 plastics per square meter per day, which amounts to >1000 metric tons of plastic deposition to western U.S. protected lands annually.”

In other words, plastics microfibers travel great distances, pollute ecosystems and are breathable.

Mikaela Whitman, partner in the Insurance Recovery Group of the law firm Pasich LLP, based in New York, said, “I think you're going to see a whole new wave of liability for plastic exposure. And with microplastics in particular, as they're finding them all over the place.”

Due-Diligence Issue

Whitman, who represents policy holders, says, “I'm saying to my company, to my clients, you need to think about this going forward. What are your policies covering you for? And you're going to have to be aware of what your interaction is with plastics.”

Banks and other financial institutions could come to scrutinize companies more carefully regarding how they handle plastics, in the context of their obligations to shareholders.

Whitman believes lenders should especially be wary of the management of these liabilities.

“I think it's going to turn to more boards of directors getting sued," she says. “If you invested in a company that didn't manage their plastic properly, they're going to open themselves up for suits that they breached duty to shareholders."

Plastics and Climate Risk

Climate change is also likely to become intertwined with plastics and microfibers as it becomes increasingly and strategically important. Companies theoretically do well by reducing carbon footprints and creating greater social value.

“The world we live in is now using more resources than the planet can produce, and so reusing what we have in a sustainable manner is of critical importance,” said INVL Baltic Sea Growth Fund partner Vytautas Plunksnis, when the private equity fund in June took a majority stake in Eco Baltia. “We intend to focus on food grade recycled plastics (rPET) capacities expansion that will ultimately contribute to a reduction in carbon footprint and promote environmental sustainability.”

Whitman uses U.S. Clean Air Act enforcement as a cautionary example. If a firm has known violations, new discoveries of microfiber production can only worsen their risk exposure.

“These are things that give shareholders the ability to say, 'Look, you shouldn't have invested in this company. There's evidence out there. They're polluting the air. They're not managing their plastics correctly,'” Whitman says. “I do think banks and lenders should be paying close attention. And I know they do typically when they're doing their disclosure. But it's another thing to add on as evidence that a company is not managing itself correctly.”

“Plastics make a direct contribution to climate change,” says a November 2019 United Nations Environment Program report about pollution and the insurance industry. It says, “Plastics, which are made from fossil fuels, account for 20% of total oil consumption, and their manufacture, recycling and incineration is energy intensive, resulting in high carbon emissions. Just like climate change-related risks, this study shows that plastic pollution risks can affect insurance and investment portfolios in the form of physical, transition, liability and reputational risks.”

The reputational can stem from insurers' client relationships with, or investments in, high plastic polluters, as well as increasingly high-profile campaigns mounted by NGOs such as Greenpeace.

Vigilance and Opportunity

Threats to human health and evolving liability claims connected to marine litter and plastic pollution should be closely monitored by insurers, it adds.

“At the same time, plastic pollution presents significant opportunities for insurers to position themselves on the frontline in tackling this global issue and in helping to secure a more sustainable future,” the UN states, also noting that “recognizing their responsibility . . . many insurers have committed to promoting economic, social and environmental sustainability - or sustainable development.”

“It makes sense from a risk management perspective,” says Pasich's Mikaela Whitman. “If you're managing the risk on the front end, hopefully you have less exposure down the road when there are issues of plastic pollution allegations, potential bodily harm, in terms of the oceans, all the effects on ecosystem. And what does that cause? This is a waterfall effect from there.”

Topics: Green Finance & Sustainable Business, Nature Risk Management