My 4-year-old son learned to ride a bicycle recently. This was not only a great accomplishment but also provides a perfect metaphor for risk professionals, especially now as we turn our attention to the risk of rising prices with economies moving from recession to recovery.

The first lesson from bike riding is obvious: we need to constantly maintain balance. Every successful risk manager strives to be neither overly pessimistic nor optimistic in their assessments, lest they lose credibility. In large part, this involves having the right data and models for quantitative analysis, but it may also require us to keep emotions in check to ensure we aren't biasing our interpretation of the numbers.

Bike riding requires forward momentum. Similarly, risk management is not a passive activity, and we must constantly monitor the environment around us. Ideally, our course corrections are so minute that they fail to attract attention. But over time, small changes can have a meaningful impact and be even more effective than a sudden shift in strategy.

Just ask my son. Distracted by a construction site, he swerved his bicycle at the last second to avoid a tree branch, only to land in a ditch. (Don't worry, he's fine.) The episode emphasized a valuable lesson for risk practitioners: the need for constant vigilance.

The Current Case for Higher Inflation …

Responding to the pandemic, governments swerved their policies to avoid both a public health crisis and an economic depression. We avoided an even worse economic outcome, but now face potential unintended consequences. Specifically, for those economies now experiencing accelerated growth, such as the U.S. and China, all attention is turning to the specter of inflation.

Risk managers across industries are therefore asking: Will we see prices rise uncontrollably? How bad could the situation get? And what can we do about it?

The case for higher inflation rests primarily on the assumption that economic growth going forward will be strong, because of aggressive (i.e., dovish) monetary policy from central banks and the unprecedented levels of fiscal stimulus. With too many people chasing after too few goods, price increases will be sure to follow. We've already seen some evidence of this “demand pull” in the prices of commodities such as gasoline, copper and lumber.

… And the Case Against

While this logic and the recent evidence of price inflation are compelling, for price increases to be sustained, we would have to assume that demand will continue to outstrip supply indefinitely.

However, given that unemployment rates remain high in the U.S. and in many parts of the world, it's likely that the supply of goods and services will steadily increase to meet demand as businesses ramp up production. Moreover, temporary dislocations brought on by supply-chain disruptions during the pandemic will fade as vaccinations rise, putting downward pressure on prices.

So, Who's Right?

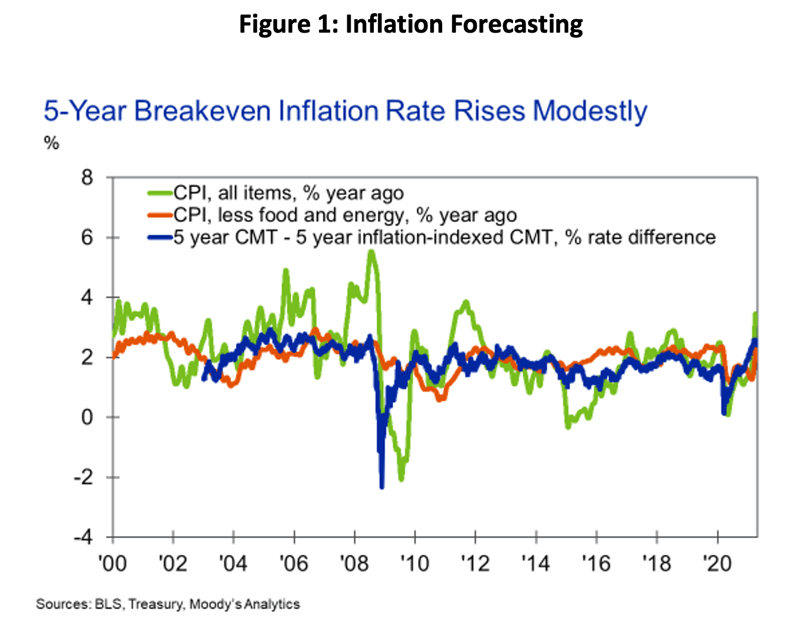

Inflation forecasting has been a nemesis of macroeconomists and professional forecasters alike. The “breakeven inflation rate,” implied by the difference in yield between nominal and inflation-indexed Treasury bonds, has had mixed performance as a predictor of inflation historically. What's more, forecasting overall inflation is particularly challenging, given the sheer number of individual prices within the economy and the complexity of shifting supply and demand factors - as well as investor sentiment and expectations.

Today, the 5-year Treasury rate spread suggests inflation in the U.S. should trend close to 2.6% per year over the next five years. This seems reasonable, considering the Federal Reserve's stated objective of allowing inflation to rise above its 2% target in the short term, as part of an effort to return the economy back to full employment as soon as possible.

But, as with bike riding, it's hard to predict when you might ride over a nail or blow out a tire. The best thing firms and risk managers can do, given the uncertainty, is to plan around this baseline view of inflation but also allow - and prepare for - the distinct possibility that inflation will come in either significantly higher or lower than forecasted.

The Scenario Mapping Solution

From a practical perspective, we can handle the effect of changes to the inflation outlook on our analysis by adopting scenario mapping - a process that has already proved useful for quickly adjusting the weights we place on alternative scenarios when computing, say, expected losses for IFRS 9, CECL or other applications.

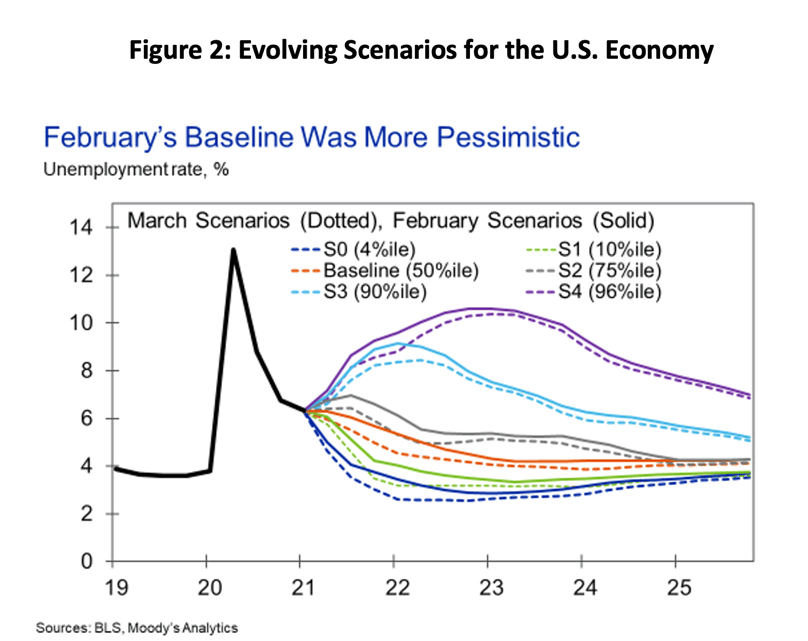

The following example is illustrative. Most economists upgraded their outlook for the U.S. economy in March, primarily for three reasons: (1) COVID-19 vaccination programs advanced faster than anticipated; (2) economic stimulus turned out to be larger than expected; and (3) consumers rapidly increased their spending on goods and services.

Rather than running a full loss-estimation process, which may take days or even weeks, we can approximate the effect of this evolving view of the economy by calibrating (or “mapping”) the distribution of economic scenarios from February into March's distribution.

Applying this mapping to all scenarios allows us to adjust their percentiles - and, by extension, the scenario weights we would assign to each of them. The result of this mapping exercise might imply that February's baseline scenario migrated upward in the distribution, from a 50th percentile event to a more pessimistic 66th percentile.

Although this scenario-mapping process does involve some key assumptions regarding the distributions and the specific economic indicators used in the calibration, it allows institutions to adapt to a dynamic environment by quickly making reasonable adjustments to their expected loss forecasts. Implementing these small course corrections on a monthly basis may be more palatable, and lead to less disruption, than making large step changes in the forecast quarterly or annually.

Parting Thoughts

A significant portion of risk management involves dealing with human behavior and emotions. One lesson learned from both the COVID-19 pandemic and the Great Financial Crisis is how prone we may be to herd behavior and jumping to conclusions. Forecasters were too dire in their initial predictions early in the pandemic, and may now have turned overly optimistic a year later.

Confirmation bias, myopia and herd behavior are just a few of the psychological pitfalls that managers must navigate above and beyond quantitative assessment and analysis of risks.

Plan continuation bias may be one of the most difficult behaviors to overcome. This was evident in January and February of 2020, when reports of a new disease were dismissed as a local threat. Even as evidence mounted in the U.S. and other countries that this mysterious illness was spreading, many organizations were reluctant to deviate from the business plans they had carefully crafted.

While no panacea, scenario mapping can provide us with a method for continuously evaluating and adjusting to economic and other risks as they emerge. Adopting this and other mechanisms in our daily routines can ensure that we proactively - and continuously - adjust our outlook while keeping our biases in check.

When it comes to handling the emerging risk of inflation, just follow my son's advice: regularly maintain your bike (or your models), stay alert, avoid danger (with scenario mapping), and use a helmet (or other insurance).

Cristian deRitis is the Deputy Chief Economist at Moody's Analytics. As the head of model research and development, he specializes in the analysis of current and future economic conditions, consumer credit markets and housing. Before joining Moody's Analytics, he worked for Fannie Mae. In addition to his published research, Cristian is named on two U.S. patents for credit modeling techniques. He can be reached at cristian.deritis@moodys.com.