In the global economy, there are some worrisome trends that could put economic growth at risk. Financial vulnerabilities have been intensifying worldwide as financial conditions remain relatively easy, despite the long economic recovery.

Corporate debt, for example, has been rising in many countries around the world, including the United States. In some European countries, banks are overloaded with government bonds, and some still have high levels of nonperforming loans on their balance sheets.

Policy implementation risks in some emerging markets remain high, and geopolitical factors are holding back development in others. In China, meanwhile, risks still lurk in the shadow banking sector, and the capital levels remain low in the Chinese banking sector - at all but the very largest institutions.

Vulnerabilities like these are indeed on the rise - in both advanced economies and in emerging markets - according to the IMF April 2019 Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR). A recession is not in the IMF's baseline forecast - but the slowing pace of growth has led the IMF managing director, Christine Lagarde, to call the decade-long recovery “precarious.”

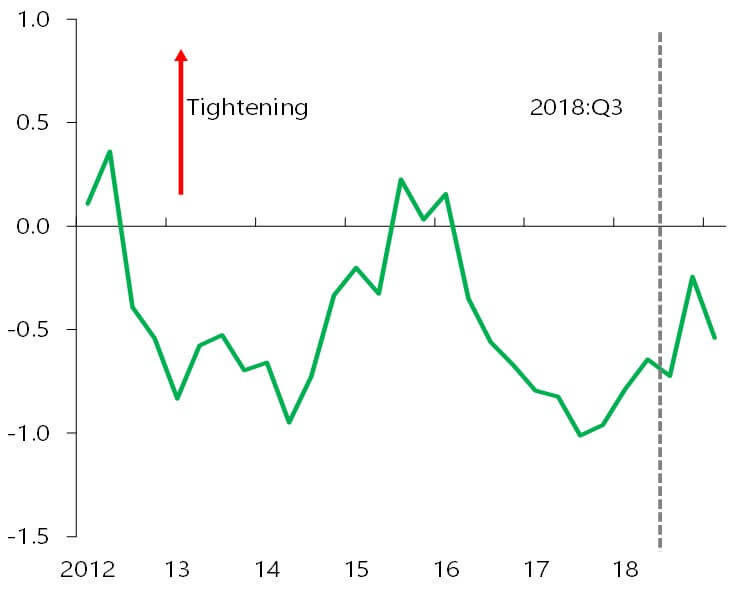

Figure 1: Global Financial Conditions, 2012 - Present

Global Financial Conditions Index (Standard deviation)

This poses a dilemma for policymakers seeking to counter a slowing global economy. By taking a patient approach to monetary policy, central banks can lessen growing downside risks to the global economy. But if financial conditions remain easy for too long (see Figure 1), vulnerabilities will continue to build, increasing the odds of a sharper decline in in economic activity at some later point.

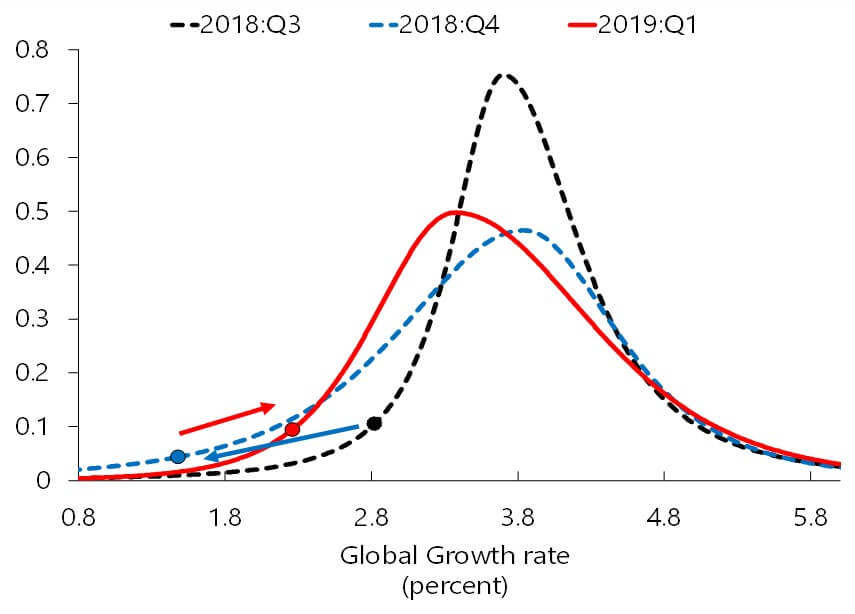

For the moment, there's some reassuring news: short-term risks to global financial stability are still low by historical standards (see Figure 2). In the medium term, however, financial stability risks remain elevated. So, it is crucial that countries adopt the appropriate mix of policies to sustain growth while keeping the rising vulnerabilities in check. This is no time for complacency.

Figure 2: Short‐Term Risks to Growth

Global Growth Forecast Densities (Probability densities)

But why are we so concerned about financial vulnerabilities? Because they could be exposed in the event of a sudden, sharp tightening of financial conditions, thus magnifying the impact of shocks to the global economy.

Possible triggers include (1) a sharper-than-expected global growth slowdown; (2) an unexpected shift to a less dovish outlook for monetary policy; (3) an escalation of trade tensions; or (4) other policy and political uncertainties. In the end, higher vulnerabilities are a harbinger of greater risks to financial stability.

Building on the IMF “Growth‐at‐Risk” methodology used for analyzing financial stability risks, the April 2019 GFSR introduces a systematic approach to quantifying vulnerabilities in the financial system, so that policymakers can monitor them in real time and take preventive steps to ease risks, as needed.

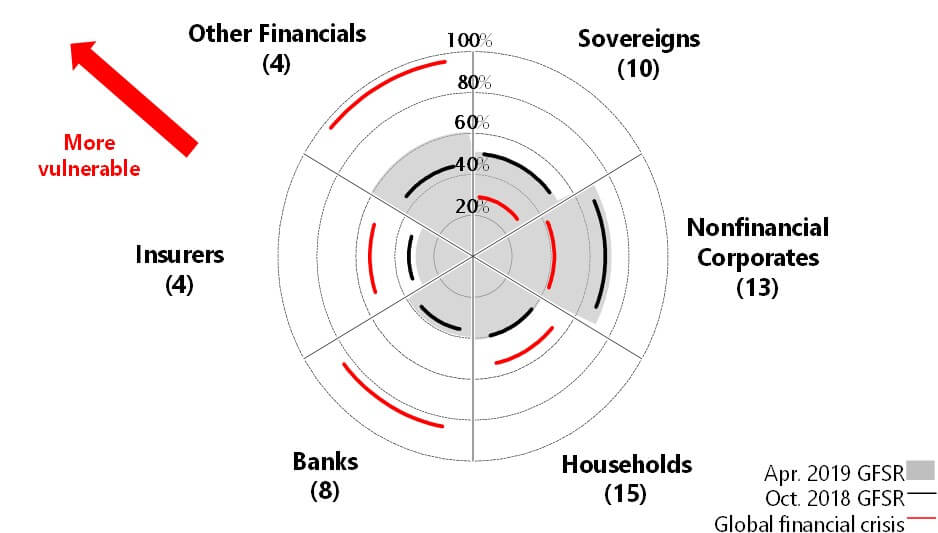

The framework includes six sectors: corporates, households, governments, banks, insurance companies and other financial institutions (the so&hyphencalled shadow banking sector). It tracks both the current level and the change of several vulnerabilities, including leverage, maturity and liquidity mismatches, and currency exposures. These vulnerabilities are tracked across 29 systemically important countries and aggregated at the regional and global level.

In Figure 3 (below), the grey area shows the proportion of countries - by their GDP - where vulnerabilities are assessed as high or medium‐high in the different sectors.

Figure 3: Financial Vulnerabilities, 2008 - Present

Proportion of GDP of Systemically Important Countries with Elevated Vulnerabilities, by Sector

(Share of countries with high and medium‐high vulnerabilities by GDP; assets for banks)

Troublesome Trends in Advanced Economies

What are some of today's most worrying vulnerabilities?

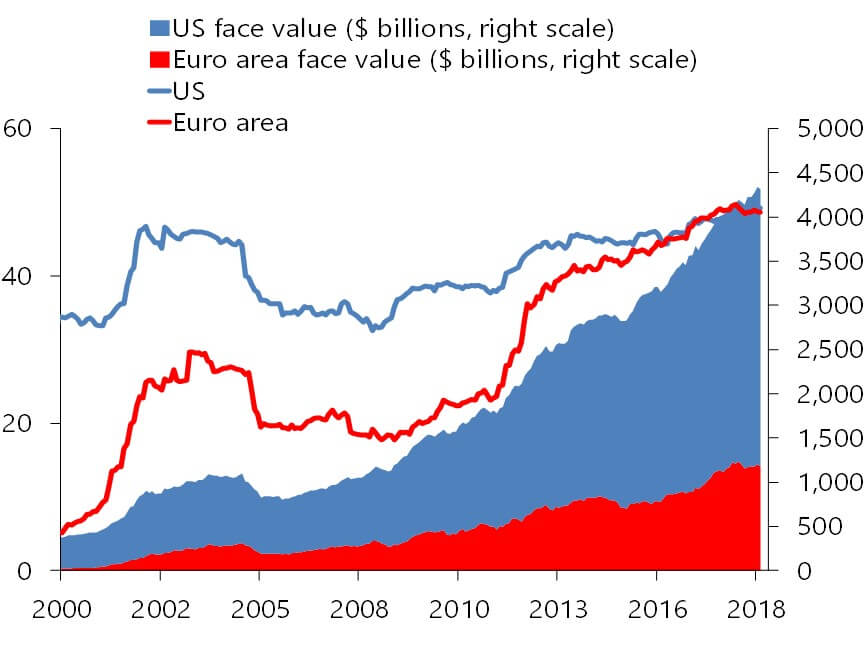

Advanced economies. Corporate debt and financial risk‐taking have increased in recent years, underwriting standards have weakened, and the creditworthiness of borrowers has deteriorated. For example, the stock of BBB‐rated bonds - one step short of a “junk” rating - has quadrupled in the United States and the euro area since the global financial crisis (see Figure 4), while speculative-grade credits have almost doubled.

Figure 4: The Outstanding Stock on BBB‐rated Corporate Bonds

BBB‐Rated Bonds in Investment Grade Indices (Percent of total; billions of US dollars)

A sharp tightening of financial conditions or a severe economic downturn could make it harder for indebted firms to repay their loans, forcing them to cut back on investment or employment. An area of particular concern, highlighted in the GFS report and in an IMF blog posted last November, are so-called “leveraged loans” to highly- indebted borrowers.

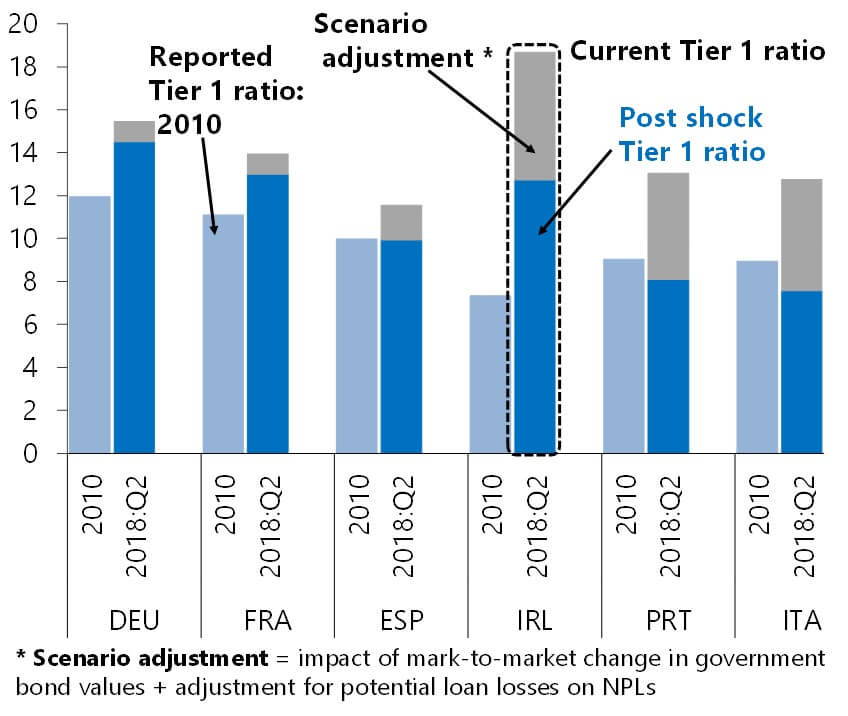

Euro area. Fiscal challenges in some European countries have rekindled worries about the sovereign-financial sector nexus - a dynamic that was at the heart of the euro crisis in 2011. A sharp rise in government bond yields could result in significant losses for banks with large holdings of government debt. Moreover, while banks have been taking steps to address nonperforming loans, these are still high at some institutions and could lead to losses in the future.

Figure 5: Potential Losses on NPLs and Sovereign Holdings, European Banks

Estimated Impact on Tier 1 Capital Ratios: Adverse Downside Scenario (Percent)

Overall, bank Tier 1 capital ratios are now higher than in 2010 in many European countries, even after accounting for potential losses on government bond holdings and on nonperforming loans (see the light blue bars in Figure 5, above). The significant exceptions to this trend are Italian and Portuguese banks, where aggregate post-shock Tier 1 capital ratios are now actually slightly lower than in 2010.

Given their large holdings of sovereign, bank and corporate bonds, insurance companies could also become entangled in the sovereign‐financial sector nexus.

Vulnerabilities in China and Emerging Markets

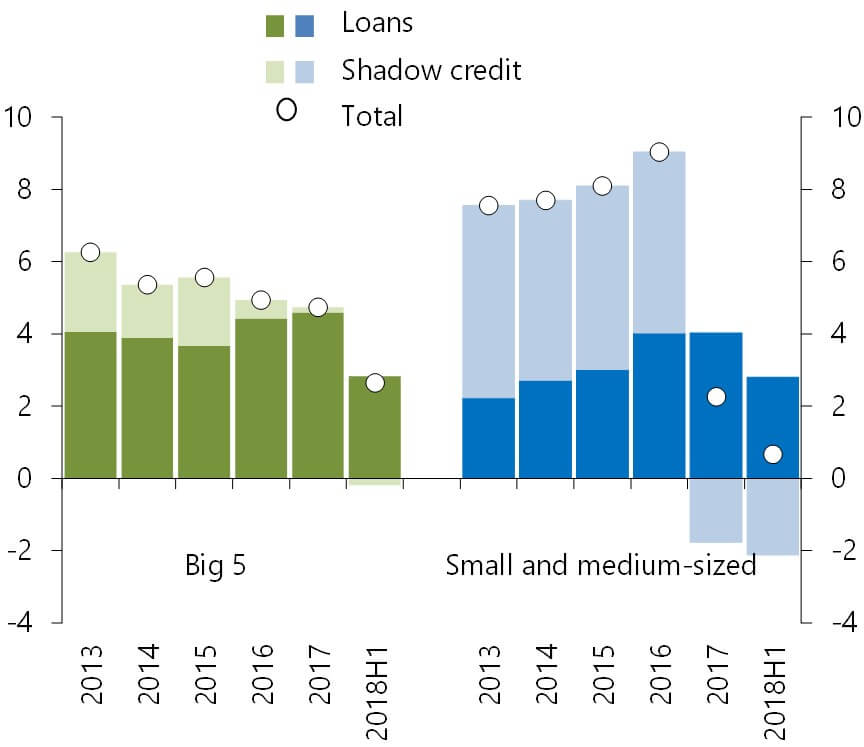

China. A decline in profitability and low levels of capital at small and medium‐sized banks is restraining credit to smaller private firms. While financial regulation has managed to curb shadow credit, especially at smaller banks, further monetary and credit support may increase financial stability risks, as continued credit growth makes it harder for smaller banks to clean up their balance sheets (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Regulatory Tightening Curbs Shadow Banking in China

Net Increase in Bank Credit (Trillions of renminbi)

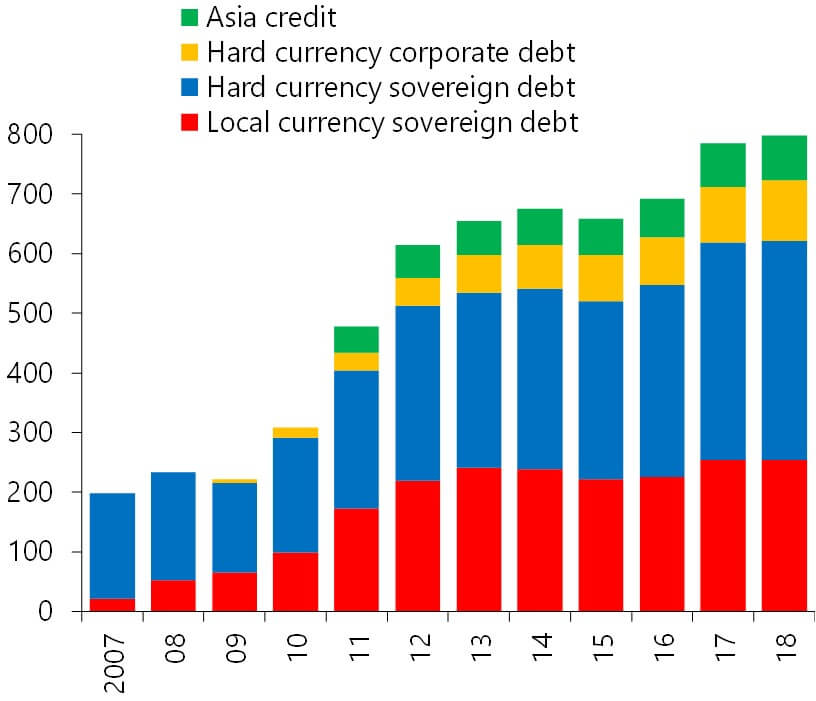

Emerging Markets. Portfolio flows to emerging markets are increasingly influenced by the behavior of benchmark-driven investors who seek to match the returns of popular indexes. For example, the amount of funds benchmarked against widely‐followed emerging markets bond indexes has quadrupled in the past 10 years (see Figure 7) to $800 billion.

Figure 7: Asset of Funds Becnhmarked Against EM Bond Indices

Assets Benchmarked against JPMorgan Emerging Market Indices (Billions of US dollars)

Index‐driven funds help expand the universe of potential investors for emerging market economies, but they also leave them more vulnerable to changes in global financial conditions and to the risk of sudden reversals of capital flows. Flows have been resilient in the past six months, but external risks may put them at risk again.

Policymaker Recommendations

In an environment in which low yields and volatility are likely to persist, there are several actions policymakers can take to contain vulnerabilities to the global financial system. Here are seven suggestions for mitigating them:

- Macroprudential tools can be used to dampen credit growth and make the financial system more resilient to shocks. One example is the countercyclical capital buffer, which requires banks to increase capital when credit is growing.

- Countries with high levels of corporate debt should consider developing macroprudential tools for highly-leveraged firms - especially when credit is provided by nonbank lenders.

- In the euro zone, lowering the debt‐to‐GDP ratio among highly‐indebted governments, and further repairing banks' balance sheets (especially by addressing nonperforming loans), should be high priorities to reduce risks.

- Authorities in China should continue to reduce leverage in the financial sector, especially in the shadow banking sector, and ensure that weaker lenders build capital buffers. Policymakers, moreover, should carry out the reforms they have announced - particularly those aiming to address risks in investment products.

- Emerging market economies facing volatile capital flows should limit reliance on short‐term overseas debt and ensure that they have adequate foreign currency reserves and fiscal buffers.

- A rollback of regulatory reforms should be avoided, and the integrity of the institutional framework for macroprudential oversight should be strengthened.

- If macroprudential tools prove insufficient to mitigate medium‐term risks to financial stability, consideration should be given to using monetary policy to “lean against the wind” in countries with a strong cyclical position and inflation at or above target.

Bottom Line

If policymakers pursue an appropriate combination of policies to address financial vulnerabilities, countries can sustain the economic expansion while also reducing potential risks to financial stability.

Tobias Adrian is the Financial Counsellor and Director of the Monetary and Capital Markets Department at the International Monetary Fund.

Fabio Natalucci is Deputy Director of the Monetary and Capital Markets Department at the International Monetary Fund.

The authors are grateful to the members of the IMF's Global Markets Analysis Division for their work on the April 2019 Global Financial Stability Report. This article is based on the main conclusions of that report.