In mid-May, the Federal Reserve Board released its Financial Stability Report, representing its “current assessment of the resilience of the U.S. financial system.” Needless to say, the Fed is keeping a close watch on the scope and economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and elevated vulnerabilities to financial stability and systemic shocks.

And the U.S. central bank has not minced words. While expressing the conventional view that “the financial regulatory reforms adopted since 2008 have substantially increased the resilience of the financial sector,” the report says, “the financial system nonetheless amplified the shock, and financial sector vulnerabilities are likely to be significant in the near term.”

Noting that “some sectors of the economy have been effectively closed since mid-March,” Fed chair Jerome Powell said in a May 13 speech, “The scope and speed of this downturn are without modern precedent, significantly worse than any recession since World War II . . . This reversal of economic fortune has caused a level of pain that is hard to capture in words . . . The path ahead is both highly uncertain and subject to significant downside risks.”

A few days later, in a CBS 60 Minutes interview, Powell explained, “I was really calling out a risk that I think is an important one for people to be cognizant of, the risk of longer-run damage to the economy.”

As influential as its voice and its sobering outlook may be in economic policymaking, the Fed is not alone in financial stability monitoring. In addition to other regulators and multilateral bodies like the Financial Stability Board and International Monetary Fund, private sector organizations ranging from the Brookings Institution to McKinsey & Co. to Oliver Wyman have mobilized considerable intellectual and analytical firepower toward similar ends.

The combination and diversity of viewpoints can only be a plus as a variety of scenario-driven perspectives contribute to a virtual dialogue, shedding light on uncertain futures and outcomes. Better to identify and address exposed vulnerabilities sooner rather than later, all agree.

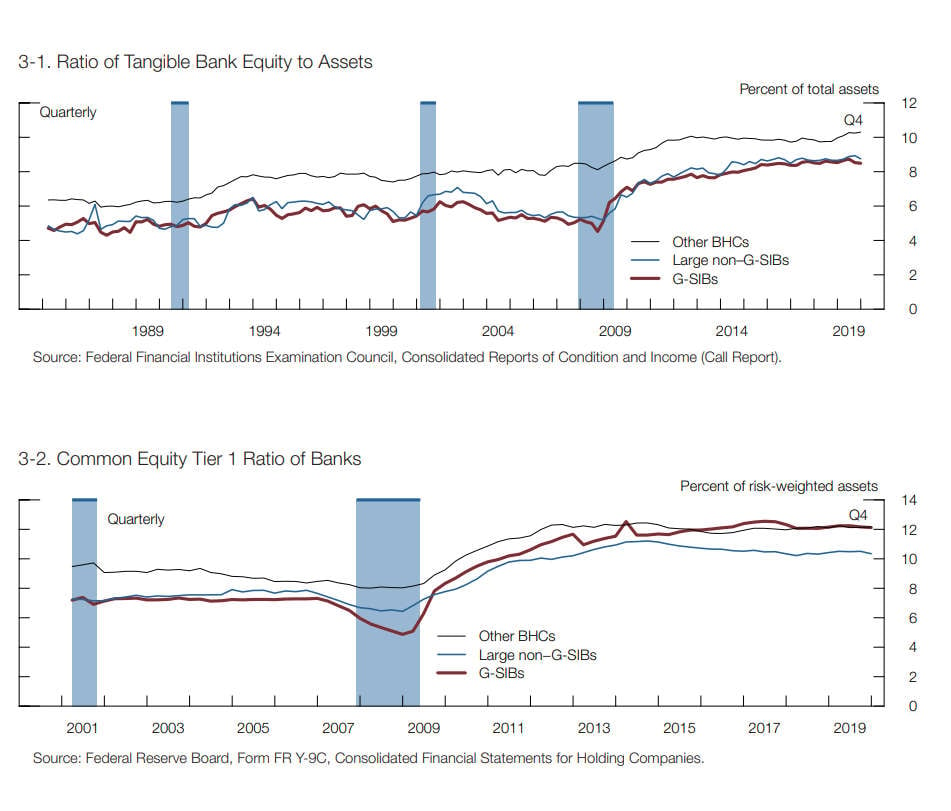

Loss-absorbing capacity at historically high levels “permitted banks to absorb the increased credit provisions and draws on credit lines associated with the onset of the pandemic,” says the Federal Reserve's Financial Stability Report.

Loss-absorbing capacity at historically high levels “permitted banks to absorb the increased credit provisions and draws on credit lines associated with the onset of the pandemic,” says the Federal Reserve's Financial Stability Report.

Salient Shocks

The Federal Reserve's latest, semi-annual stability report includes a section on “Near-Term Risks to the Financial System.” It lists 17 possible “salient shocks” identified from a survey of “22 contacts at banks, investment firms, academic institutions and political consultancies.”

The six most-cited shocks over 12 to 18 months: COVID-19; efficacy of global policy response; corporate debt/credit cycle turn; U.S. election; market structure/liquidity; and geopolitical risks.

COVID-19 was No. 1 by a wide margin, with a score above 80%. Respondents “highlighted a range of operational, financial, and policy risks related to the outbreak,” according to the document, and “noted that lockdowns were likely to amplify operational vulnerabilities at firms; they cited the potential for remote or home-based trading activity to weaken market functioning and for financial institutions' offshore back-office operations to be disrupted.”

“The pandemic could persist for a prolonged period or reemerge, further delaying the recovery of U.S. economic activity and leading to strains on the financial system that worsen the downturn,” the report states. That could cause the vulnerabilities and salient shocks to increase, making them more likely to further amplify negative shocks to the economy.

Could such factors bring about a new financial crisis?

In a May 22 blog article summarizing the IMF's Global Financial Stability Report, Tobias Adrian and Fabio Natalucci wrote: “Should the ongoing economic contraction last longer or be deeper than currently expected, the resulting tightening of financial conditions may be amplified by these vulnerabilities, causing more instability or even a financial crisis.”

A briefing produced in April by the World Economic Forum, following discussions held by its Platform for Shaping the Future of Financial and Monetary Systems, revealed a combination of relief and unease:

“While financial system resilience, fiscal support, regulatory flexibility and liquidity provision to date have helped ensure that the financial system is supportive of economic recovery, a more protracted slowdown may present new risks to the financial system. Thus, while the initial phase of the crisis has eased, participants are keenly aware that there may be greater turmoil affecting the financial system as the economic fallout continues, potentially precipitating a financial crisis down the line.”

Scenario Impacts

McKinsey draws on nine potential macroeconomic scenarios for the U.S. and the world, discussed, for example, in a May article, Stability in the Storm: U.S. Banks in the Pandemic and the Next Normal. In a survey of 2,079 executives worldwide, 36% expected a muted recovery in which the virus spreads globally without a seasonal decline. In the U.S., GDP could diminish by 13% from peak to trough, with unemployment reaching roughly 20%.

In such conditions, McKinsey says, economic policy would fail to prevent a huge spike in unemployment and business closures, resulting in a slower recovery even after the virus is contained.

However, over a quarter in the survey are more optimistic, anticipating an effective virus-containment or economic policy response.

Among the more positive scenarios, the most commonly selected is one in which the virus is well contained and economic policy is somewhat effective. Nevertheless, U.S. GDP would suffer in 2020, falling 8% from peak to trough, returning to its previous level of economic activity at the end of 2020.

Forty percent of the executives are more pessimistic, predicting that either virus containment or economic policy or both will be ineffective, resulting in job losses, business closures and a hard road back to prior economic activity.

In a muted recovery, McKinsey analysts say, most countries would take more than two years to recover to pre-virus levels of GDP, with the U.S. achieving that in first quarter, 2023. China would see a 4.4% drop, returning to prior levels in 2021's fourth quarter, and Europe an 11.1% decline, with restoration in 2023's third quarter.

Losing Years of Progress

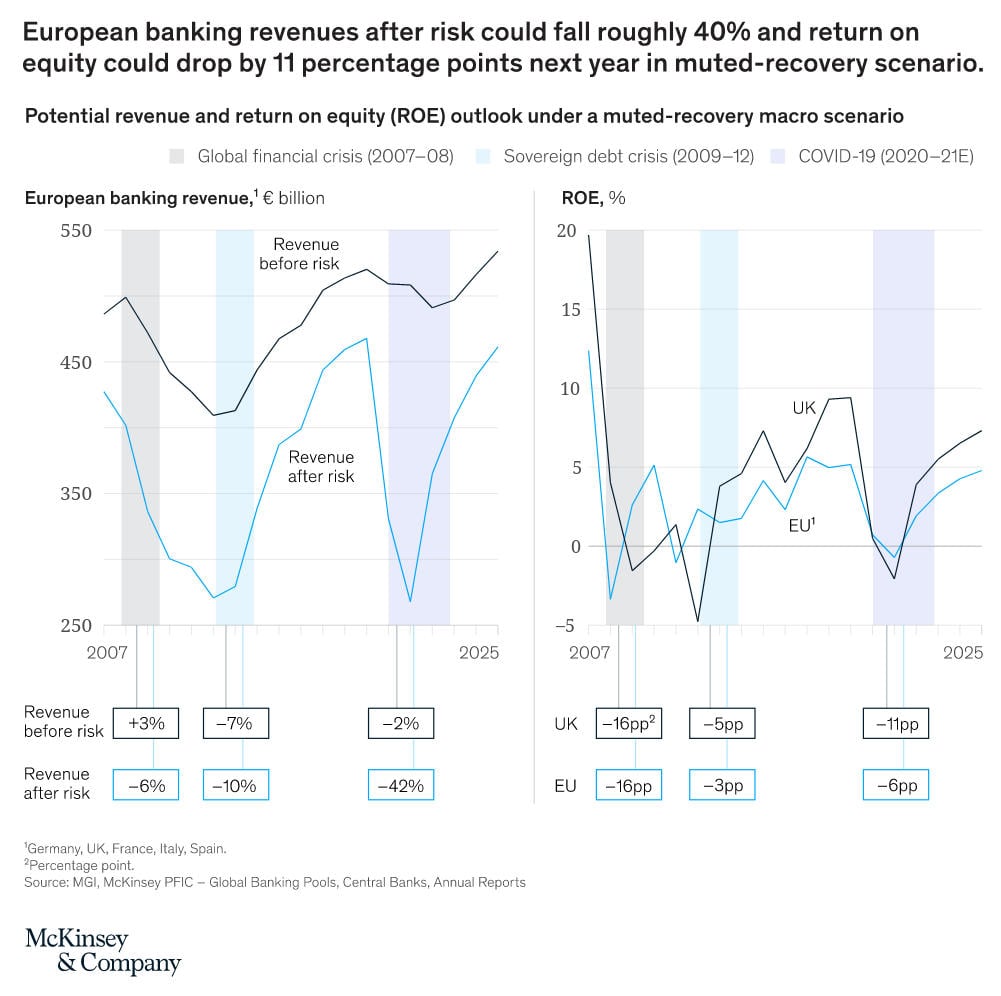

In No Going Back: New Imperatives for European Banking, McKinsey says that the crisis will put European banks through prolonged stress. A muted recovery - viewed as the most probable scenario - would lead to sharp drops in bank revenue, a squeeze on capital and declining return on equity.

“In essence, the sector could lose four years of economic progress,” McKinsey says. “The scenario would therefore be more severe for banking economics than the 2007-2008 financial crisis or the 2010 European debt crisis.”

The consulting firm does offer some hope for European banks, outlining six imperatives to help mitigate the downsides. One entails the advancement of technology innovation, allowing banks to identify which customers they can feasibly serve, the launch of more personalized services, and introduction of subscription-based advisory services to small businesses and customers seeking retirement advice.

Another step entails doubling down on risk and capital management, with credit losses being the defining differentiator of bank performance over the next year. Early detection and proactive intervention will be critical to manage non-performing loans.

McKinsey also advises turning the rapid loan-origination processes employed during relief programs into “business as usual.” This will require the use of sophisticated digital credit decisioning tools and a huge step-up in decision accuracy and “time to yes” procedures.

And McKinsey says banks should start to shed and carve out non-core assets and acquire new technology-based capabilities as needed, with many fintech firms becoming acquisition targets. Digital channel usage in European countries has grown as much as 20% during the pandemic period, the report notes.

Risks of Recurrences

Deutsche BÖrse Group financial intelligence subsidiary Qontigo walked through four COVID-19 recovery scenarios in late May, from relatively benign to far worse:

- A rapid and successful turnaround in which the virus subsides and there is a coordinated reopening of the economy.

- A slow recovery and mismanaged reopening of the economy, leaving public companies to chart their own course. This shakier return means longer unemployment, less capital expenditure and more conservative investor behavior.

- A second spike in infections, and with no vaccine in sight, a second wave of lockdowns, sending markets plunging.

- A financial over-reaction in which uncertainty reigns, investors raise questions about the fundamental values of companies, and the inevitable recession reveals the fragility of global supply chains and workforces. In addition, liquidity dries up, and recovery is delayed until late 2021.

According to Qontigo managing director of applied research Melissa Brown, the firm modeled each scenario's impact on the S&P 500 and 10-year U.S. Treasury yields over the next two years. Such stress testing is a helpful complement to Value-at-Risk, Brown says: “When you look at VAR only, you can miss some of the risks.”

Olivier d'Assier, Qontigo head of applied research for the APAC region, says financial firms would benefit from assigning probabilities to all four scenarios, adjusting them over time as more data becomes available.

“Thus far, markets have been buying the first scenario, or a V-shaped recovery,” D'Assier says. By the third quarter, “we will see if that scenario is correct or not.” He believes that savvy market watchers are keeping all scenarios in mind, weighing their respective probabilities over time, and considering the most severe outcome as a distinct possibility.

As of early June, d'Assier gauges the four scenarios' probabilities, respectively, as 50%, 10%, 30% and 10%. “An aggressive reopening [scenario 3] is what we currently have, so now it is all up to consumers' behavior whether it is a successful reopening or whether it turns into a super-spreader event,” d'Assier says.

Credit Crises and Cost Structures

A May article from Oliver Wyman, The Real Credit Crisis, states that it was a misnomer to label the crisis of 2008 that way. Today's reality is that risks are growing significantly due to credit misallocation. There are increased solvency risks for corporates and small- and medium-size enterprises, and the risk of spill-over info failure in parts of the financial system.

Oliver Wyman analysts assert that public authorities must work in tandem with the financial services system to address these issues in order to speed the economic recovery, employing a more targeted approach to credit provision and relying on banks' expertise to achieve scale. In particular, banks' savvy in restructuring troubled companies will become increasingly important, as well as their critical function in traded debt and other financial markets.

The firm recommends several actions to support economic growth and ensure financial stability: Course-correct on credit provision to small and mid-size businesses so that stimulus gets to those that truly need help; prepare to manage a potentially large corporate solvency crisis that will arise after the initial liquidity support, with new restructuring vehicles likely to be required; prepare to intervene in parts of the financial system as second-order financial stability issues arise and weaker banks start to fail; and plan loss absorption for future outbreaks. This means finding a way for government, business, investors, banks and insurers to work together to put in place a systemic solution for pandemic re-insurance.

Marsh, a Marsh & McLennan Companies affiliate, as is Oliver Wyman, in a June 2 report on pandemic risk protection, makes a case for “a public-private pandemic risk solution, which can accelerate the U.S. economy's recovery and provide protection against future risks.”

The right combination of participants and incentives can, over time, ”spur new technologies, ways of working, services, insurance products, and processes to ultimately chip away at the enormous losses associated with pandemics,” Marsh president and CEO John Doyle says in the foreword. ”That, in turn, can help make pandemic risk more manageable and enable our economy to build the necessary resilience it needs for the future.”

Another Oliver Wyman paper advises financial institutions to reset their costs to a level that allows them to be profitable for the business profile they will have moving forward, after the coronavirus crisis passes. One approach is to develop scenarios to compare reversion to a business-as-usual cost structure with more of a “digital revolution” model.

In the latter, customers continue using digital channels for many activities, there is a significant increase in work-from-home arrangements, client meetings are almost exclusively conducted online, there is a radical reduction in the range of products offered and a streamlining of front-to-back processes.

Understanding expense-base changes under different scenarios will require an investment in improved transparency around the drivers of cost, allowing a firm to answer such critical questions as: Where are inefficiencies that drive up the cost base? How to inject variability into the cost base during times of uncertainty? What levers can most reliably and effectively move the needle on costs?

Treasuries as Case Study

For a May 27 webinar of the Brookings Institution's Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy, COVID-19 and the Financial System - How and Why Were Financial Markets Disrupted?, Darrell Duffie of the Stanford Graduate School of Business presented a background paper, Still the World's Safe Haven?, explaining concerns about the behavior of the secondary market for U.S. Treasuries in March, when the pandemic crisis triggered investor flows that overwhelmed intermediaries.

As the pandemic fears struck, “The Treasury market wobbled quite badly, becoming dysfunctional,” Duffie says, and the Fed had to step in. Although the Fed was able to restore order through what Duffie describes as “an unprecedented rate of Treasury purchases and other actions” - taken with what chair Jerome Powell termed “unprecedented speed and force . . . to restore functionality in these critical markets” - the professor believes that the market revealed itself to be overdue for a design upgrade.

Duffie suggests that the government conduct an analysis of market structure, though in his estimation, Treasuries should be centrally cleared. “In this way, the Treasury market will be less reliant on dealer balance sheets,” and far less likely to be dysfunctional during times of stress.

Itay Goldstein, the Joel S. Ehrenkranz Family Professor of Finance at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School, presented a paper on the fragility of the corporate bond markets and investment funds.

“There was a dramatic increase in spreads and decrease in liquidity in corporate bond markets in March,” Goldstein says, alleviated only by the Fed intervention. Meanwhile, stresses on investment funds led to massive outflows.

“We need to ask what to do, aside from depending on the Fed to act” in extreme circumstances, Goldstein says. He proposes that actions be taken to improve liquidity in underlying corporate bond assets; reduce liquidity available to investors; and employ swing pricing systems to help reduce stress on these markets.

Fragile Interconnections

Donald Kohn, a Brookings Economic Studies senior fellow and former Fed vice chair, summed up key points of the webinar by noting that solutions to COVID-19-related market stresses include central clearing of Treasuries, central clearing in the repo market, reform of the mutual fund market and increased bond liquidity. He also wondered if, given all the fragilities revealed in the securities markets, history needs to be repeated with a Dodd-Frank-type regulatory response.

According to Nellie Liang, another Brookings senior fellow, formerly the founding director of the Fed's Division of Financial Stability, money fund reform can and should be addressed by the Securities and Exchange Commission, with assistance from the Financial Stability Oversight Council.

In a May 13 statement, SEC chairman Jay Clayton and S.P. Kothari, chief economist and director of the Division of Economic and Risk Analysis, described an “Interconnectedness Initiative” to identify “significant channels of risk exposure and risk transfer in our domestic and global financial system, with an eye toward identifying areas of vulnerability and stability.” The effort involves collaboration with the FSOC-linked Office of Financial Research, the Financial Stability Board and others “to examine select portions of these markets and initially identify which participants, activities and linkages act or function as the originators, transmitters, amplifiers, absorbers and ultimate owners of risk.”

Liang believes that there needs to be more public and government discussion of the fragilities and potential instabilities that have been revealed during the crisis. The key question that needs to be asked and answered, Liang says, is, “What is the amount of risk we want to live with in the financial system? For now, we have some risk [management] pieces in place, but not all.”

Katherine Heires is a freelance business journalist and founder of MediaKat llc