“Shadow banking” is a catchy phrase that sounds sinister, sly, slick or shady. Yet that phrase obscures an important fact: Although some forms of shadow banking can be risky, complex or even toxic, as witnessed during the financial crisis 10 years ago, not all forms of shadow banking are necessarily dangerous.

In fact, with the implementation of post-crisis financial regulatory reforms, a significant portion of the shadow banking sector has “graduated” into the less complex, more transparent realm of “market-based finance.”

Resilient nonbank financial intermediation (NBFI) - the new terminology adopted by the Financial Stability Board - is crucial in fostering efficient financing through different sources and in allocating capital to the sectors of the economy where it is needed. But with the financial landscape evolving rapidly, and with nonbank financial intermediation continuing to grow, it is imperative to assess emerging threats and risks outside the traditional banking sector.

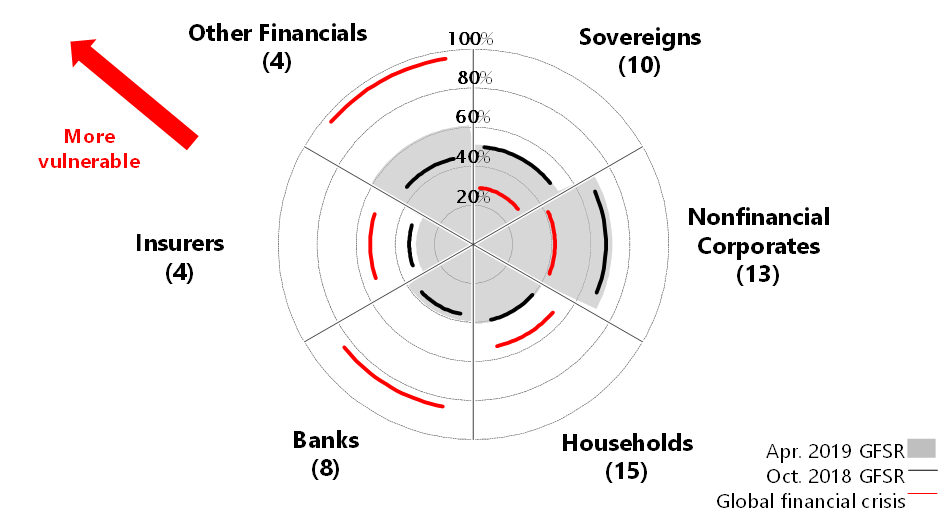

The IMF's most recent Global Financial Stability Report, released in April 2019, introduced a new structured, systematic approach to monitor vulnerabilities across regions and sectors. This new framework, summarized by the “radar chart” below, detected elevated vulnerabilities in several sectors around the world - fragilities that could turn into amplification channels should an adverse shock occur.

As the chart below shows (see Figure 1), these fragilities are growing in the “other financials” sector: Sixty percent of systemically important countries by GDP have high or medium-high vulnerabilities in that sector.

Figure 1: Financial Vulnerabilities, 2008-Present

Proportion of GDP of Systemically Important Countries with Elevated Vulnerabilities, by Sector (Share of countries with high and medium-high vulnerabilities by GDP, assets for banks; number of vulnerable countries in parenthesis)

Sources: Bank for International Settlements; Bank of Japan; Bloomberg Finance L.P.; China Insurance Regulatory Commission; European Central Bank; Haver Analytics; IMF, Financial Soundness Indicators database; S&P Global Market Intelligence; S&P Leveraged Commentary and Data; WIND Information Co.; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: The global financial crisis reflects the maximum vulnerability value from 2007 to 2008.

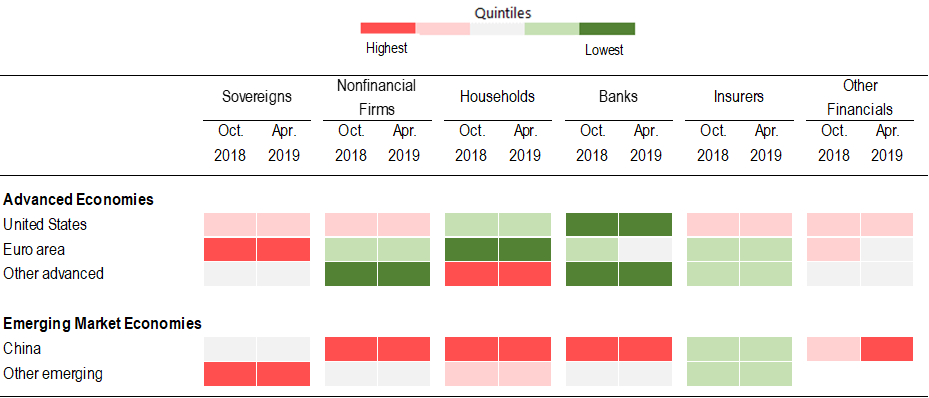

Looking at the distribution across regions, vulnerabilities in the “other financial” sector are elevated in the United States and China.

Figure 2: Financial Vulnerabilities by Sector and Region

Sources: Bank for International Settlements; Bank of Japan; Bloomberg Finance L.P.; China Insurance Regulatory Commission; European Central Bank; Haver Analytics; IMF, Financial Soundness Indicators database; S&P Global Market Intelligence; S&P Leveraged Commentary and Data; WIND Information Co.; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Red shading indicates a value in the top 20 percent of pooled samples of advanced and emerging market economies for each sector from 2000 through 2018 (or longest sample available), and dark green shading indicates values in the bottom 20 percent. Other systemically important advanced economies comprise Australia, Canada, Denmark, Hong Kong SAR, Japan, Korea, Norway, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Other systemically important emerging market economies comprise Brazil, India, Mexico, Poland, Russia, and Turkey.

Let's now consider two case studies of possible emerging risks in NBFI in the U.S. and China.

Leveraged Lending in the U.S.

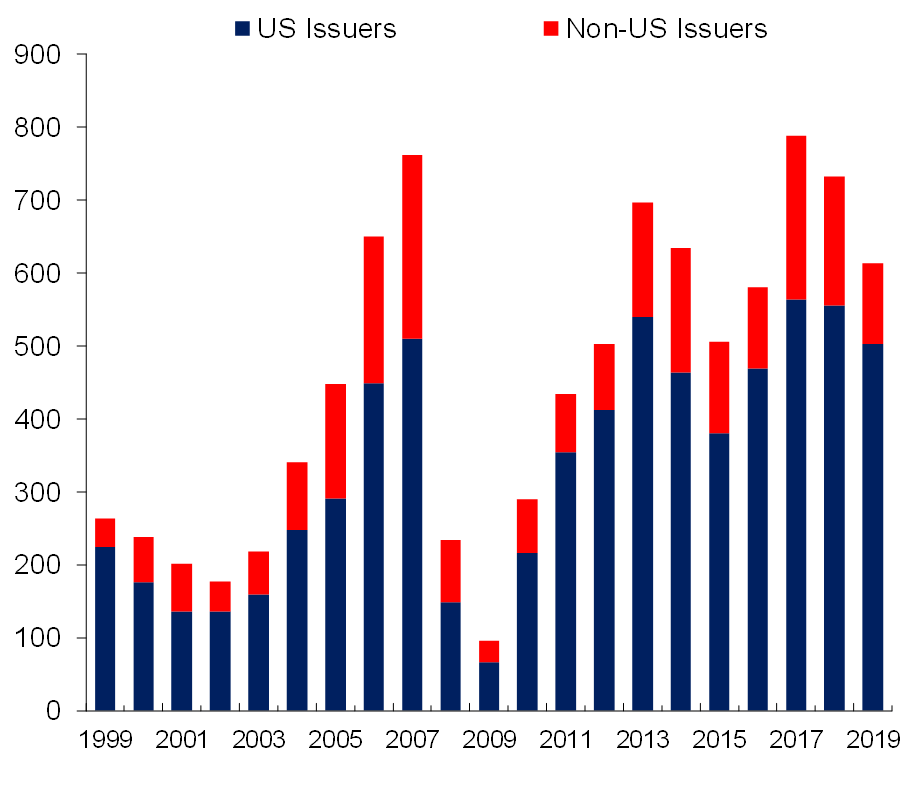

First, consider the case of the U.S. leveraged loan market. In recent years, this market has increased in size, complexity and riskiness. Issuance has reached record highs, with leveraged loans increasingly used to fund financial risk-taking through mergers and acquisitions and leveraged buyouts, dividends and share buybacks.

Figure 3: Global Leveraged Loan Issuance

New Issue Global Leveraged Loan Volume (Billions of US dollars)

Sources: S&P LCD and IMF staff calculations

Note: 2019 issuance is through Q1 and annualized to estimate full-year 2019 issuance.

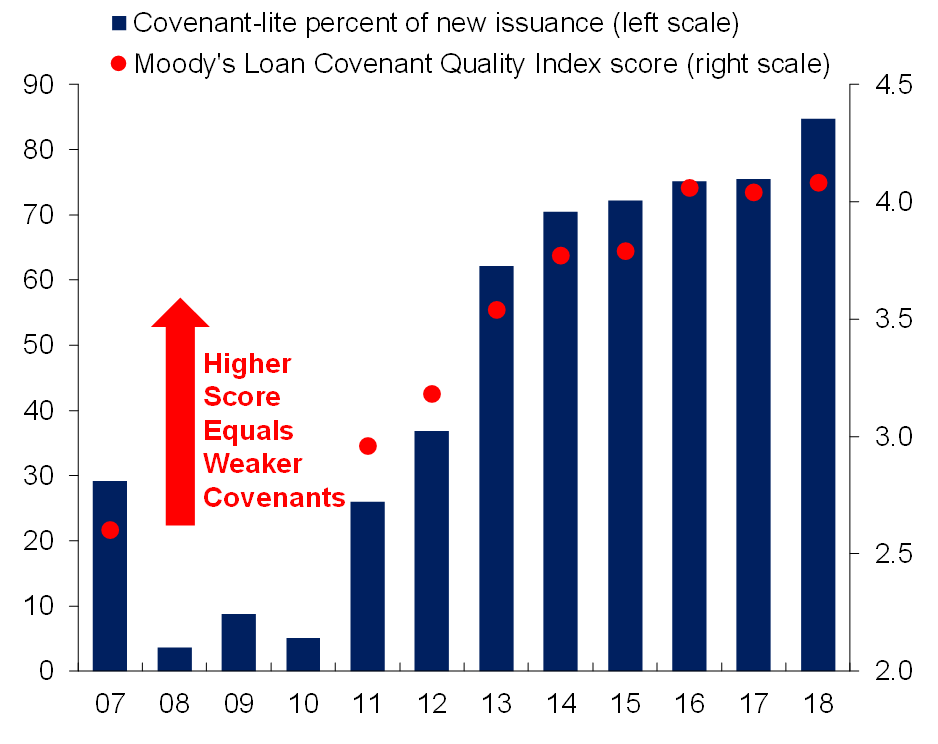

Credit quality is deteriorating because of looser underwriting standards, weaker investor protections and a higher share of weaker credits.

Figure 4: Weakening Covenant Protections

New Issue Covenant-Lite US Leveraged Loans and Covenant Quality Index

Sources: Moody's; S&P LCD; and IMF staff calculations

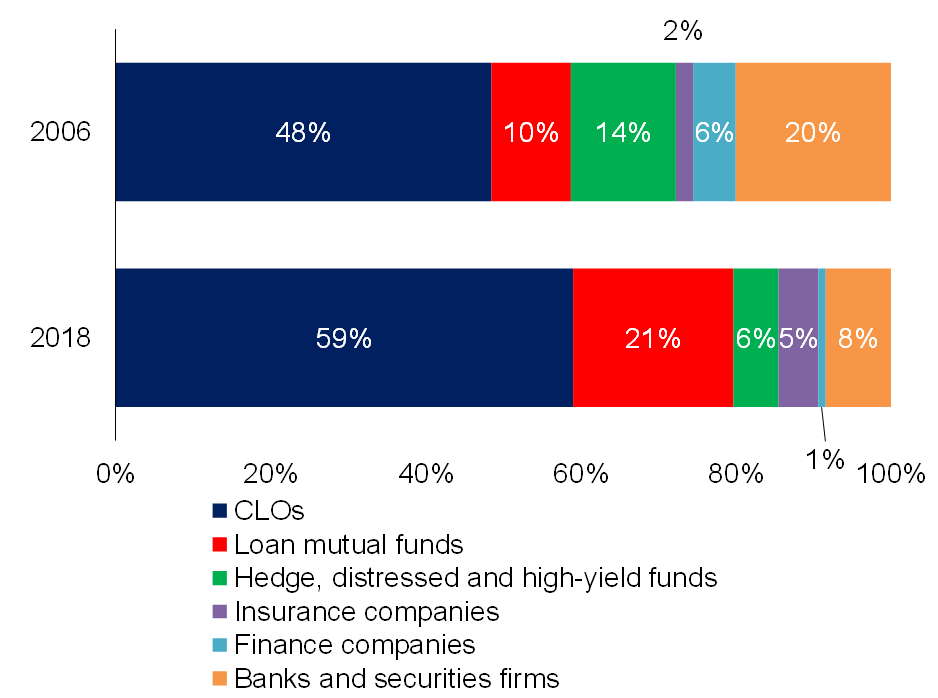

After years of rapid growth, the stock of leveraged loans outstanding is approaching that of high-yield bonds, while the investor base for leveraged loans has shifted toward nonbank investors.

Figure 5: Shift toward Institutional Investors

US Leveraged Loan Investor Base (Percent of new issuance)

Source: EPFR Global; S&P Leveraged Commentary and Data; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: CLO = collateralized loan obligation.

With growing signs of late-cycle dynamics that are reminiscent of past episodes of investor excess, there is a concern that the leveraged loan market could face distress in the event of a sudden sharp tightening in financial conditions. But how bad could it be? Would it be a systemic event? Or would a freeze in the loan market simply act an amplifier, magnifying the impact of an economic downturn?

Institutional investors are less central to the financial system and have a different risk profile and appetite than banks, so this reallocation of risks in the loan market may be efficient from a risk allocation standpoint. However, it's uncertain how investors would behave in the event of significant strains in the loan market - and it's unclear whether they would continue to provide credit or simply “run for the exits.”

Moreover, analysts may have neglected indirect exposures and so-called “contingent liabilities” at banks - i.e., they may have overlooked channels through which exposures to the loan market may resurface on the banks' balance sheets in the event of stress.

Overall, while the possibility of a systemic event in the loan market seems to be limited at the moment, a shutdown of the market could have significant negative implications for the overall economy, given the growing size of the market and the role it plays in channeling funding to corporations.

China's Shadow Banking Risks

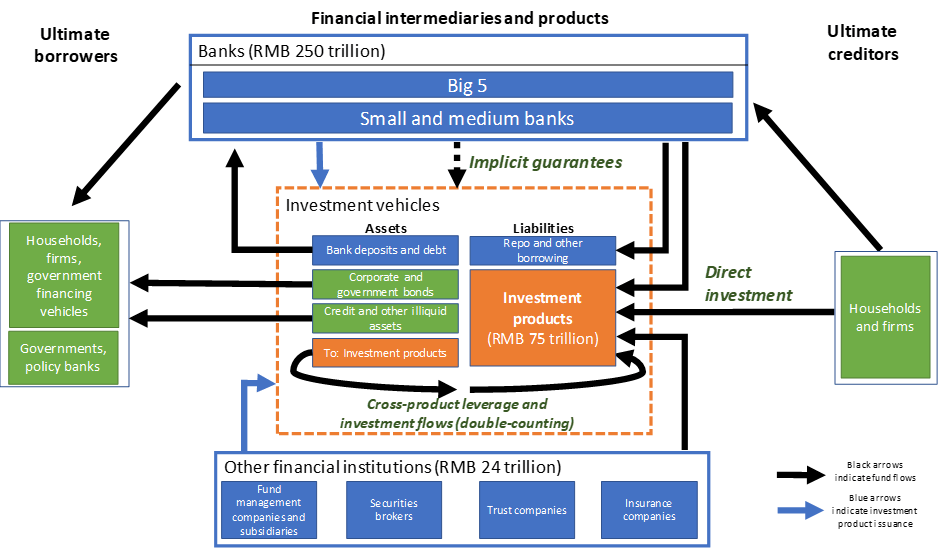

Let's also consider the case of the shadow banking sector in China and the extent to which large-scale and opaque interconnections of the Chinese financial system pose stability risks.

Figure 6: Stylized Map of Linkages within China's Financial System

Source: Asset Management Association of China; CEIC; ChinaBond; People's Bank of China; and IMF staff estimates.

Note: Investment products include non-principal-guaranteed bank-issued wealth management products and asset management products issued by other financial institutions depicted. Numbers shown are total on-balance-sheet assets for banks and financial institutions, and total investment products outstanding as of end-2017 or latest available reporting period. Numbers for other financial institutions do not include fund management companies and their subsidiaries due to lack of data. See also Ehlers, Kong, and Zhu (2018).

China's banking system is tightly linked to the shadow banking sector through its exposure to off-balance-sheet investment vehicles. These vehicles are largely funded through the issuance of investment products, with roughly half sold to multiple investors as high-yielding alternatives to bank deposits and half held by single investors, including banks. They invest in various traditional assets (such as bonds, and bank deposits) and nonstandard credit assets, as well as in other investment products. Insurance companies also have considerable exposure to these vehicles.

These relatively little-regulated vehicles have played a critical role in facilitating China's historic credit boom and have helped create a complex web of exposure between financial institutions. Banks are exposed to such vehicles along many dimensions - as investors, creditors, borrowers, guarantors and managers. These vehicles rely on banks' short-term financing to use leverage and to manage their maturity mismatches. Banks, consequently, receive significant flows from these vehicles in the form of deposits and bond investments.

Banks and other financial institutions are also direct investors in investment products. Small and medium-sized banking institutions and insurance companies are particularly exposed, with investment products accounting for one-fifth and one-third of their assets, respectively. About one-quarter of investment-vehicle assets, in turn, are invested in other vehicles, leading to opaque cross-holding and leverage structures that are difficult for regulators and investors to monitor.

Moreover, banks are seen as implicitly guaranteeing the investment products they manage, which allows them to package high-risk credit investments as low-risk retail savings products.

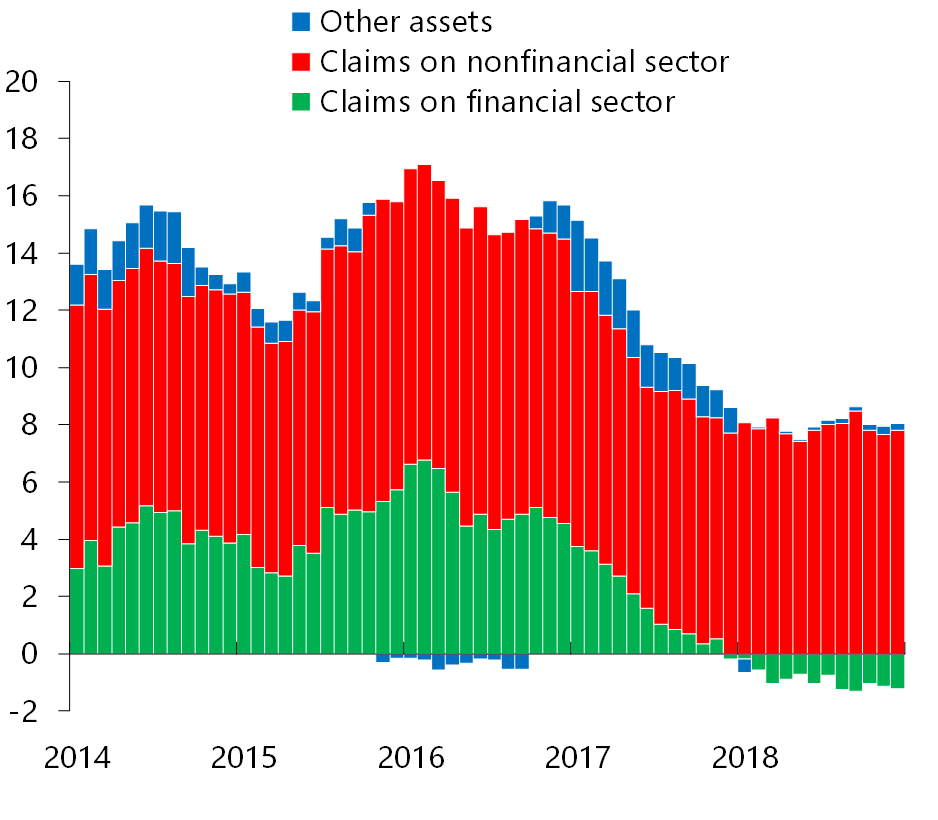

The Chinese authorities have tightened the regulatory framework to curb leverage and interconnectedness in the financial sector. While vulnerabilities remain elevated, regulatory tightening has succeeded in containing the buildup of risks.

Since the start of China's wide-ranging and welcome campaign to strengthen macroprudential and microprudential regulation nearly two years ago, bank asset growth has slowed considerably, driven by a sharp reduction in claims on other financial institutions.

Figure 7: Reduced Linkages Between Financial Institutions

Contribution to Bank Asset Growth (Percent, year-over-year growth)

Sources: Bank annual reports; CEIC; Haver Analytics; SNL Financial; Wind Information Co.; and IMF staff calculations.

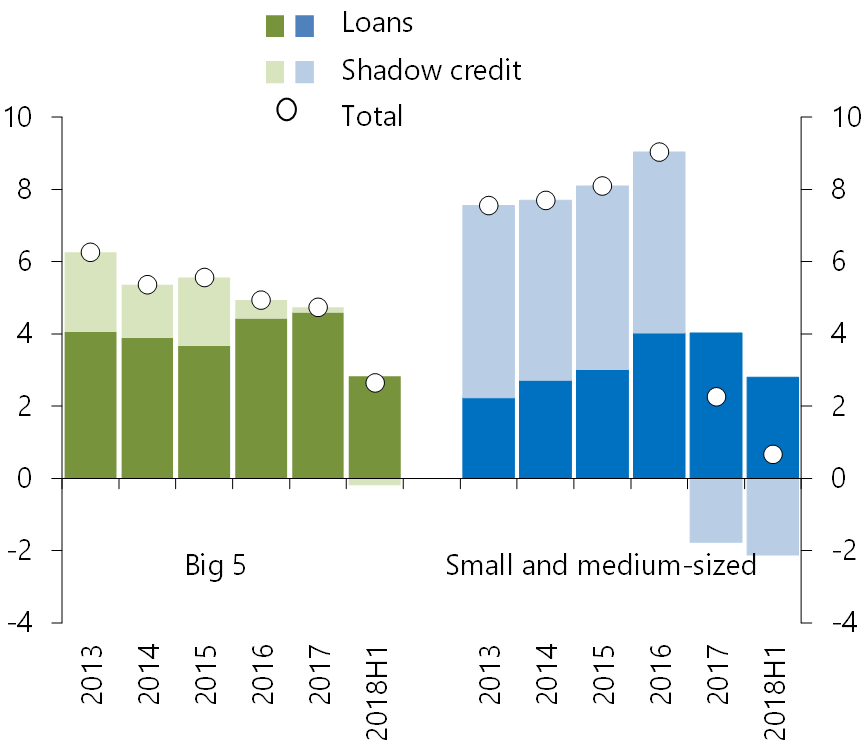

Indeed, banks in China have largely stopped increasing credit via on- and off-balance-sheet investment vehicles, leading to slower overall shadow credit growth.

Figure 8: Shadow Credit has been Curbed at Smaller Banks

Net Increase in Bank Credit (Trillions of renminbi)

Sources: Bank annual reports; CEIC; Haver Analytics; SNL Financial; Wind Information Co.; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Shadow credit includes both bank-reported on-balance sheet investment vehicles (disclosed holdings of unconsolidated structured entities) and off-balance sheet investment vehicles. The latter is estimated as 65 percent of disclosed off-balance sheet wealth management products, which roughly deducts the proportion of assets that are claims on financial or public sector counterparties; as reported in China Bank Wealth Management Market Annual Report 2017.

The slowdown was led by a sharp contraction in lending by small and medium-sized banks, which were previously the biggest contributors to the shadow credit expansion. But less progress has been made in reducing vulnerabilities related to the opaque and still-large stock of investment-vehicle assets. The regulatory reforms of China's asset management sector, introduced in late 2017, have recently been scaled back somewhat, opening opportunities for more risk-taking within the sector.

As a result, wealth management products still contain significant maturity and liquidity mismatches, as well as leverage to provide yields well above corporate bond yields. Moreover, money market borrowing by investment vehicles remains elevated.

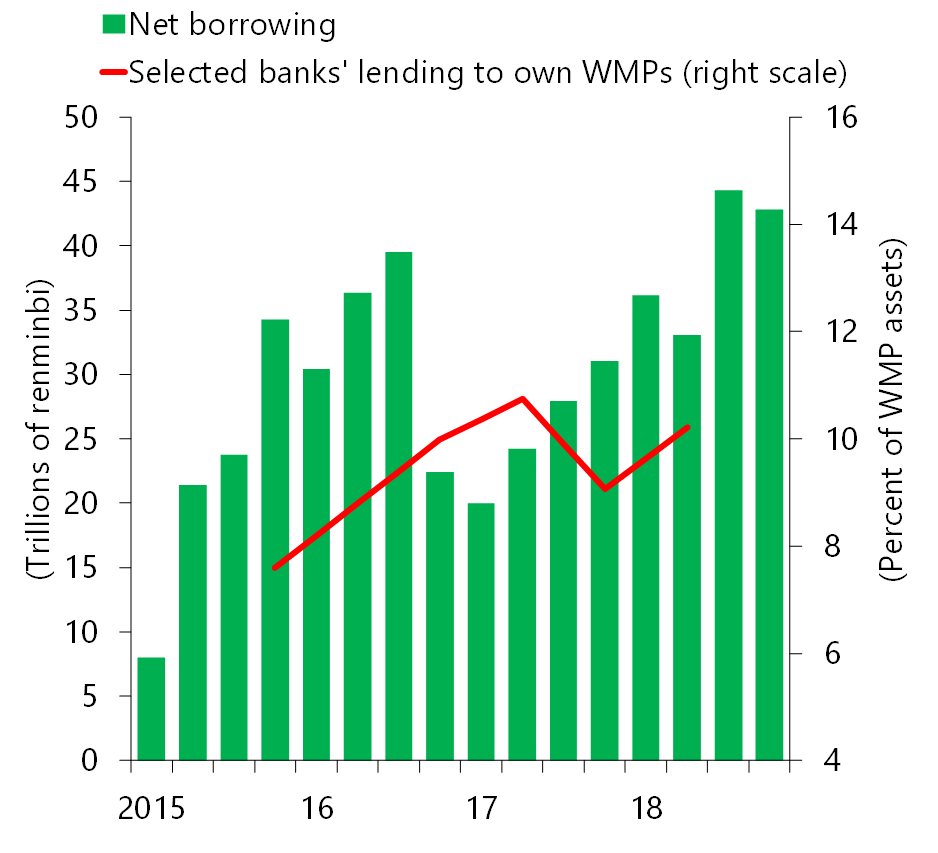

Figure 9: Rising Short-Term Borrowing

Investment Vehicle Borrowing in Interbank Market and From Sponsor Banks

Sources: Bank annual reports; CEIC; Haver Analytics; SNL Financial; Wind Information Co.; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Selected banks' lending to own WMPs based on banks with available disclosures, including for Big 5 banks and two mid-sized banks that accounted for 43 percent of off-balance sheet WMPs as of 2018:H1. WMP = wealth management product.

Parting Thoughts

So, 10 years after the global financial crisis, where have we ended up, in terms of risks in the financial sector? The good news is that the “center” of the financial system - the banking sector - has been fortified and is undoubtedly safer, with more capital and more liquidity.

However, risk has not disappeared: It has moved to the “periphery” of the financial system - shadow banking. This segment is still relatively opaque and complex, at least in some corners, with limited visibility for policymakers.

For example, data on structured loan products like collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) are still limited, preventing policymakers from gaining a comprehensive view of risks and the allocation of such risks across investors.

Financial sector policies should tackle financial vulnerabilities in an environment in which low yields and volatility are likely to persist. Policymakers should be proactive in deploying macroprudential tools.

Currently, policy tools to contain vulnerabilities are predominantly administered through banks. Only a few macroprudential tools are available to contain excesses in the nonbank financial sector, and they are largely untested. It is imperative that countries develop and expand their macroprudential toolkits to slow the buildup of vulnerabilities.

Fabio M. Natalucci is Deputy Director of the Monetary and Capital Markets Department at the International Monetary Fund.

He is grateful to the members of the IMF Global Markets Analysis Division for their work on the April 2018, October 2018 and April 2019 Global Financial Stability Reports. This article is based on the main conclusions of those reports.