From interest and exchange rates to rising inflation and fears of recession, the International Monetary Fund’s latest World Economic Outlook delineates all-too-familiar pain points for households, businesses, financial and commodity markets and governments. They are compounded by continuing repercussions from COVID-19, the war in Ukraine, a slowdown in China, and “countries accounting for about one-third of the global economy poised to contract this year or next,” IMF economic counsellor Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas said in annotating the fund’s bearish global growth forecast.

“Overall, this year’s shocks will re-open economic wounds that were only partially healed post-pandemic,” Gourinchas warned on October 11. “In short, the worst is yet to come and, for many people, 2023 will feel like a recession.”

The IMF has continually voiced concern about disparate impacts and “global fragmentation,” as economic shocks disproportionately burden lower-income countries, with financial and geopolitical implications that the rest of the world ignores at its peril.

IMF economist Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas

Indicating that “poverty and inequality are increasing,” IMF First Deputy Managing Director Gita Gopinath said in a June speech, “The pandemic is estimated to have pushed an additional 75 million people into extreme poverty in 2021, relative to pre-pandemic trends,” subsequently exacerbated by the Ukraine conflict. “We are already seeing how higher food prices and constraints on food supply are resulting in increased food insecurity, especially in the Middle East and Africa, where food accounts for 40% of consumers’ spending.”

Dollars and Debt

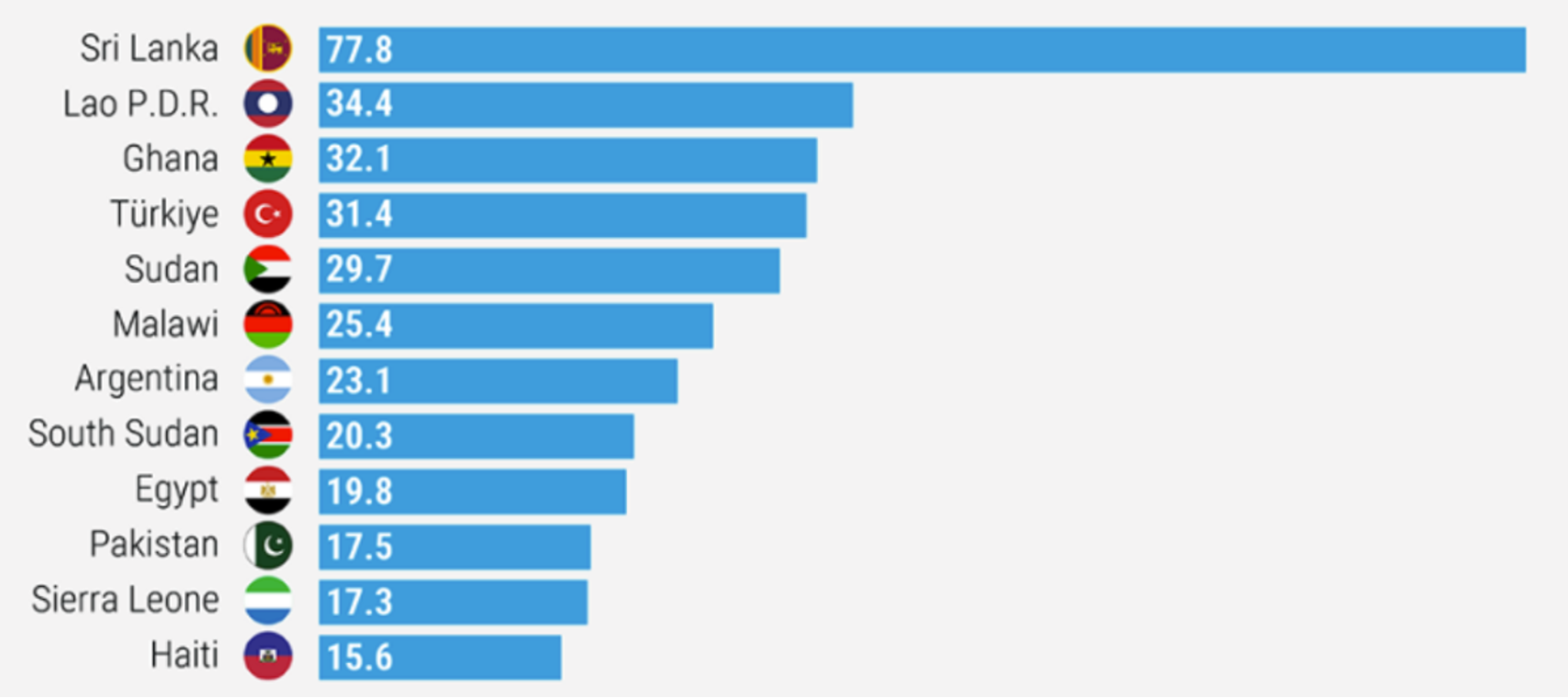

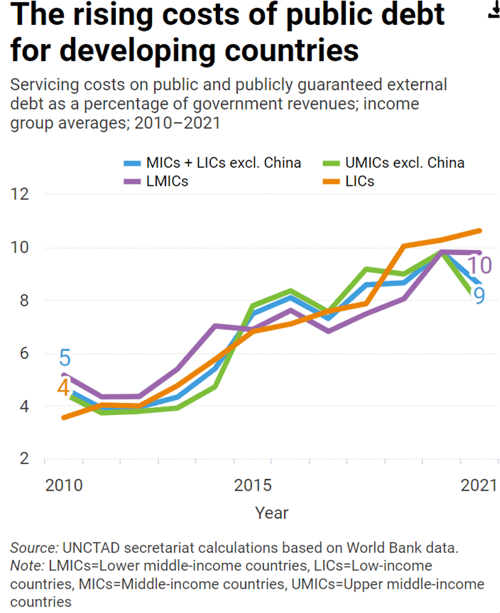

Simmering beneath headline indicators like price inflation and GDP are debt and default risks, particularly affecting emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs). Considering the significant appreciation this year in the value of the U.S. dollar, and that 90% of emerging market debt is dollar-denominated, “as the global economy is headed for stormy waters, now is the time for emerging market policymakers to batten down the hatches,” said Gourinchas, quoting from the IMF’s October report. “Too many low-income countries are in or near debt distress.”

Global government debt is projected to be 91% of GDP in 2022, 7.5 percentage points above pre-pandemic levels, despite a recent reduction in the ratio for many countries. Gopinath noted in a seminar on October 11, during the week of the IMF-World Bank Annual Meetings, that about 60% of low-income countries and 25% of emerging markets are in, or at high risk of, debt distress. Six sovereigns have defaulted this year.

Nominal exchange rate depreciations against the U.S. dollar, January-July 2022, as shown in the UNCTAD Trade Development Report.

In periods of turmoil, investors’ seeking safe havens such as U.S. Treasuries could push the dollar – and debt and other costs – even higher.

Domestic inflation has complicated monetary policy “especially in low-income countries, where food accounts for half of total consumption, and has raised concerns about food security and social unrest,” the IMF report says. “Moreover, food-importing countries have seen deteriorations in their balance of payments and fiscal balances, which typically occur when social protection increases in response to higher food prices.”

“Progress toward orderly debt restructurings through the Group of 20’s Common Framework for the most affected is urgently needed to avert a wave of sovereign debt crisis,” Gourinchas wrote. “Time may soon run out.”

Spreads and Sustainability

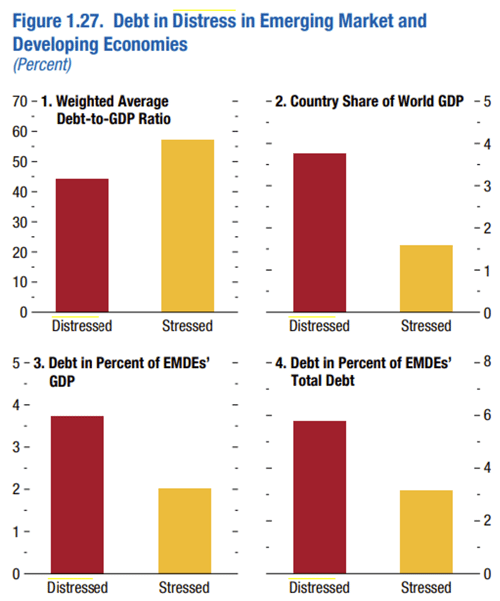

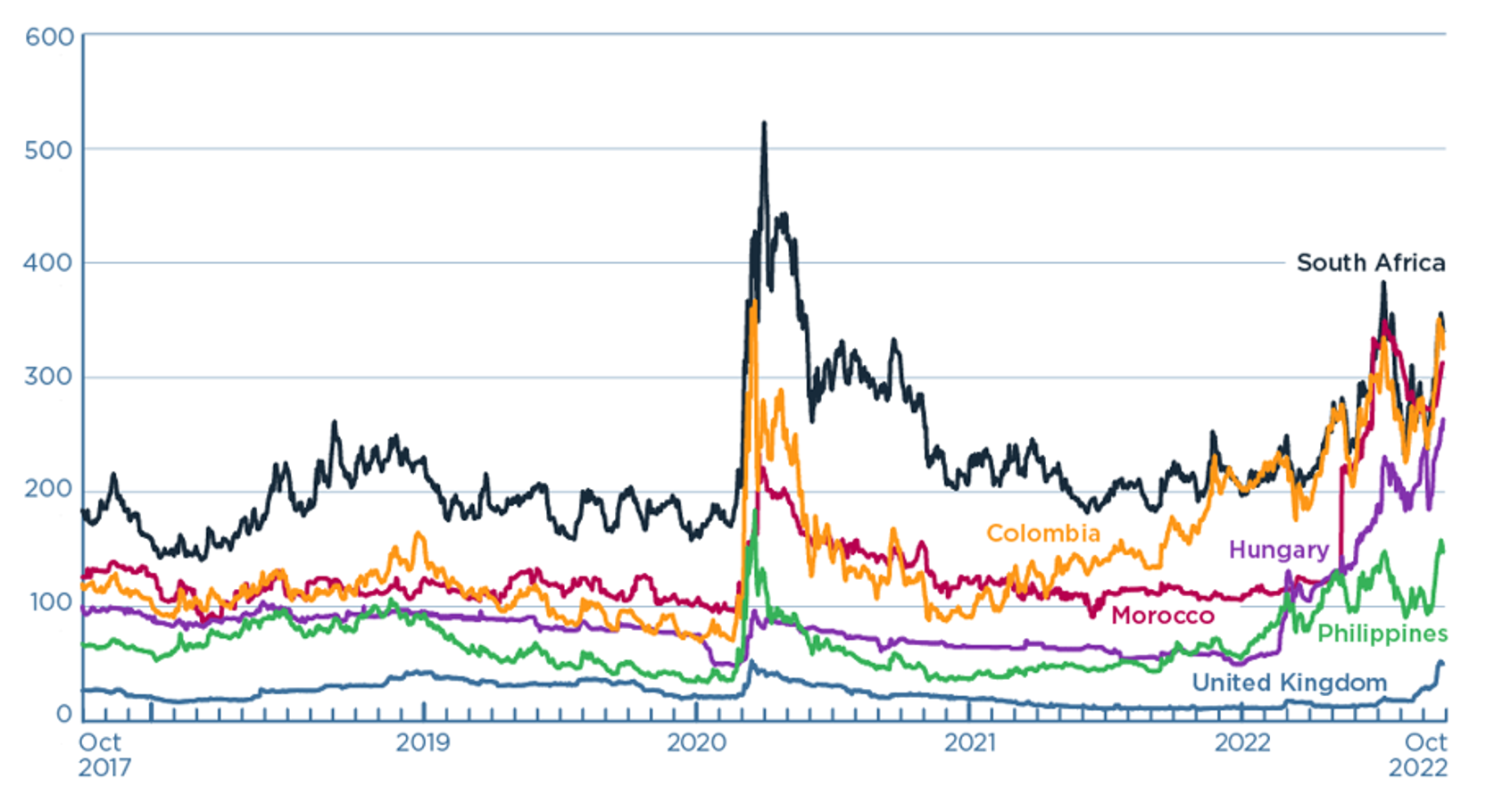

An indicator of debt distress in lower- and middle-income economies, in light of the strong U.S. dollar amid tightening financial conditions, is yield spreads – the difference between countries’ dollar- or euro-denominated government bond yield and U.S. or German government bond yields. “In sub-Saharan Africa, yield spreads for more than two-thirds of sovereign bonds breached the 700 basis point level in August 2022, significantly more than a year ago,” the IMF says. “In eastern and central Europe, the effects of the war in Ukraine have exacerbated the shifting global risk appetite.”

While some larger emerging-market economies are well positioned, according to the IMF, “if sovereign spreads increase further, or even just remain at current levels for a prolonged period, debt sustainability may be at risk for many vulnerable [EMDEs], particularly those hit hardest by energy and food price shocks.”

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook Report. Groups are classified based on sovereign spread data as of September 9, 2022. Distressed group economies have spreads greater than 1,000 basis points, the stressed group 700 to 1,000 basis points.

Released along with the World Economic Outlook was the Global Financial Stability Report, including an analysis of central bank policy responses to “high inflation, the risks of a disorderly tightening of financial conditions, and debt distress among emerging and frontier markets.”

“Financial asset prices have fallen as monetary policy has tightened, the economic outlook has deteriorated, recession fears have grown, borrowing in hard currency has become more expensive, and stress in some nonbank financial institutions has accelerated,” Tobias Adrian, financial counsellor and director of the IMF’s Monetary and Capital Markets Department, said in an accompanying blog. “Bond yields are rising broadly across credit ratings, with borrowing costs for many countries and companies already rising to the highest levels in a decade or more.”

He noted that emerging and frontier market bond issuance in U.S. dollars and other major currencies is at its weakest pace since 2015. “Without improved access to foreign funding,” Adrian wrote, “many frontier market issuers will have to seek alternative sources and/or debt re-profiling and restructurings.”

Although the global banking sector has been bolstered by high capital levels and liquidity buffers, an IMF Global Bank Stress Test suggests the buffers “may not be enough for some banks. In the event a sharp tightening of financial conditions causes a global recession next year amid high inflation, 29% of emerging-market banks (by assets) would breach capital requirements. Most banks in advanced economies would fare much better.”

Adrian described the financial stability environment as “unusually challenging . . . Though no globally systemic event has materialized so far, [policymakers] should contain further buildup of vulnerabilities by adjusting selected macroprudential tools to tackle any pockets of risk. In this highly uncertain environment, striking a balance between containing these potential threats and avoiding a disorderly tightening of financial conditions will be critical.”

“Alarm Bells Are Ringing”

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), in its 2022 Trade and Development Report, critiques “the current policy course of monetary and fiscal tightening in advanced economies.

“Supply-side shocks, waning consumer and investor confidence and the war in Ukraine have provoked a global slowdown and triggered inflationary pressures,” UNCTAD says. “All regions will be affected, but alarm bells are ringing most for developing countries, many of which are edging closer to debt default.”

Desmond Lachman, a conservative critic of U.S. central bank policy, blames years of monetary easing for saddling the world with “very much more debt in relation to the size of the global economy” than in 2008. In contrast to the 2008 bubble, warning signs – such as Evergrande and other property defaults in China, and defaulting sovereigns including Argentina and Sri Lanka – are not mainly centered in the U.S., Lachman, an American Enterprise Institute senior fellow, wrote in National Review. He finds the Federal Reserve’s current aggressive tightening “difficult to understand.” Without reversing soon, Lachman maintains, it may again be caught “hopelessly flat-footed by a global credit crisis.”

Fixed-income manager Carlos de Ancos, deputy managing director of Spain’s MAPFRE AM, says “the upward path of interest rates should be limited” as long as “inflation expectations are controlled and there is a substantial slowdown in economic growth together with a looser labor market.” Although central banks have capably handled stresses from the 2008 global crisis to the present, the risk of large imbalances following the liquidity restrictions “shouldn’t be underestimated.” Restrictive monetary policies and dollar appreciation “are the two main causes behind a tightening of access to financing for companies, especially in Europe. However, looking at the big picture, companies are showing lower leverage levels than in previous recessionary economic cycles, and we have much better capitalized financial companies.”

Risk of Crisis

UNCTAD states that “the possibility of a global debt crisis is high. Countries that were showing signs of debt distress before the pandemic – including Sri Lanka, Suriname and Zambia – are being hit especially hard by the global slowdown. And climate shocks are heightening the risk of economic instability in indebted developing countries.

“The situation in developing countries is worse than recognized by the Group of 20 major economies and other international financial fora,” the UN agency asserts. “Developing countries have already spent an estimated $379 billion of reserves to defend their currencies this year, almost double the amount of new Special Drawing Rights” recently allocated by the IMF.

UNCTAD is calling for increased liquidity and debt relief from international financial institutions for developing countries; “a larger, more permanent and fairer use of Special Drawing Rights”; and “a multilateral legal framework for handling debt restructuring, including all official and private creditors.”

On the commodities front, UNCTAD says markets have been in a turbulent state for a decade, well predating the Ukraine war. Wading into an ongoing regulatory controversy, it argues that government attention is required to curb speculative price spikes and “betting frenzies” in swaps, futures and exchange-traded funds. It also alleges that “large multinational corporations with considerable market power appear to have taken undue advantage of the current context to raise markups to boost profits on the backs of some of the world’s poorest people.”

Ameliorative Approaches

The IMF wants “eligible countries with sound policies” to urgently consider improving liquidity buffers, “including by requesting access to precautionary instruments from the fund,” Gourinchas said. “Countries should also aim to minimize the impact of future financial turmoil through a combination of preemptive macroprudential and capital flow measures, where appropriate, in line with our Integrated Policy Framework.”

Representing an EMDE perspective in an October 13 panel discussion, Nigeria’s finance minister, Zainab Shamsuna Ahmed, said that while debt servicing costs were increasing, the country took early action to manage liabilities by stretching out maturities. “We can’t just stand still when we see the risks coming.”

Gourinchas added that energy and food crises have provided a glimpse into “what an uncontrolled climate transition would look like.” Progress on climate policies as well as on debt can show “that a focused multilateralism can, indeed, achieve progress for all and succeed in overcoming geoeconomic fragmentation pressures.”

Rising five-year credit default swaps spreads on sovereign debt, measured in basis points, are a clear sign of stress. (Bloomberg data published by the Peterson Institute for International Economics)

Concluding that emerging and developing economies are closer to recession than richer countries, are “beset by capital outflows and in some cases currency depreciations approaching or beyond levels that last prevailed at the height of the panic of March 2020,” and “still laboring under pandemic legacies,” Maurice Obstfeld of the Peterson Institute for International Economics sees crises brewing “that the international financial system remains ill equipped to handle in an orderly fashion.”

The PIIE nonresident senior fellow contends in an October 6 article that it is in “the West’s” interest to provide more support for the world economy in ways “that would ease EMDEs’ policy tradeoffs while not materially undermining the battle against global inflation.”

The steps could include collective, better informed, and telegraphed central bank monetary actions; richer countries’ intervening in EMDE currency markets; and long-term commitments of adequate resources for the IMF safety net.

“Such low-cost actions would clearly be in the interest of the richer countries” in trying to avert a severe global recession and associated political costs, and to protect the international order and economic integration in the face of geopolitical threats, Obstfeld writes. “Lip service to acknowledge the EMDEs’ plight will not be enough.”

Topics: Market