The U.K. pension fund crisis raised significant concerns about the liquidity risk management strategies currently being employed by buy-side institutions. Specifically, it called into question whether liability-driven investment (LDI) is a safe and appropriate approach for defined benefit (DB) pension plans.

Pensions have very asymmetric risk (i.e., the downside risk tremendously overwhelms the upside benefit), and LDI is understandably designed to minimize the downside threat, rather than to maximize return. Essentially, it has a two-fold purpose: to match asset and liability cashflows and to reduce the volatility of pension funds’ funded status.

U.K. pension schemes were the pioneers of LDI, and among its largest users. So, how it possible that they fell into the pothole that this investment strategy was intended to protect them from?

LDI and the Pension-Fund Fiasco

The funded status of a DB pension fund is the present value of its net cash flows. It depends on the composition of assets, their growth rate, and, most importantly, the discount rate of liabilities.

LDI seeks to increase the probability that liability payments of a pension scheme will be covered. If interest rates decrease, the present value of liabilities goes up, and vice versa. In either case, if asset allocation matches the liability profile, the funded status should not be affected significantly.

Alla Gil

As long as a pension fund’s funded status hovers even slightly above a 100%, everyone is happy. In stark contrast, a deficit in funded status causes a snowball effect that could significantly impact organizations' financial health, ultimately leading to a crisis.

Most experts agree, however, that the U.K. fiasco was not the result of problems caused by LDI. Rather, it was an issue of leverage.

Prior to 2021, interest rates had been extremely low for more than a decade, and pension funds could not afford to reinvest exclusively in fixed income – because that could have led to negative cashflows.

Consequently, pension funds introduced leveraged exposure to bonds, and then used freed-up capital to invest in higher-yielding assets. However, that leverage also exposed them to potential margin calls, which were triggered when rates sharply increased.

U.K. pension funds therefore had to sell the only liquid assets they had (government bonds), causing their prices to fall and their yields to rise even further – triggering a vicious cycle that that ultimately required a government intervention.

Full-Range Scenario Analysis: How to Avoid Future Disasters

Whether such liquidity crisis was caused by pension investment managers chasing accounting rules and forgetting economics or by them getting into excessive leverage, the only approach that could have prevented this outcome is exhaustive stress testing.

Neither a simple sensitivity analysis of funded ratios to interest rate movements nor a handful of stress scenarios would have been sufficient. One needs to consider the dynamic correlations of rates, credits spreads, equity markets, and other risk factors impacting assets and liabilities.

Traditional scenario stress testing – which starts with a narrative, followed by quantification of the variables and, finally, projection of all critical performance measures – aims at false precision. It has therefore proved to be insufficient.

We’ve certainly seen examples of how an overreliance on a few scenarios designed this way can limit the effectiveness of stress tests. That was exactly the problem with stress testing of leveraged LDI pension schemes: after the decades of low inflation, risk managers underestimated the sizes of liquidity buffers needed to cover their exposures if rates increased sharply.

Complicating matters further, while the U.K. regulators called for pension funds to review their funding, liquidity and hedging positions, they didn’t demand a thorough stress testing way beyond even increased market volatility. Rather, the sharp rise in yields was pronounced to be an “extreme event,” which basically served to excuse the unpreparedness of the pension funds.

In contrast, a full range of scenarios generated with adequate breadth – not targeting precision but focusing on the tail risk – would have enabled pension managers and regulators to assess the magnitude of the leveraged LDI disaster.

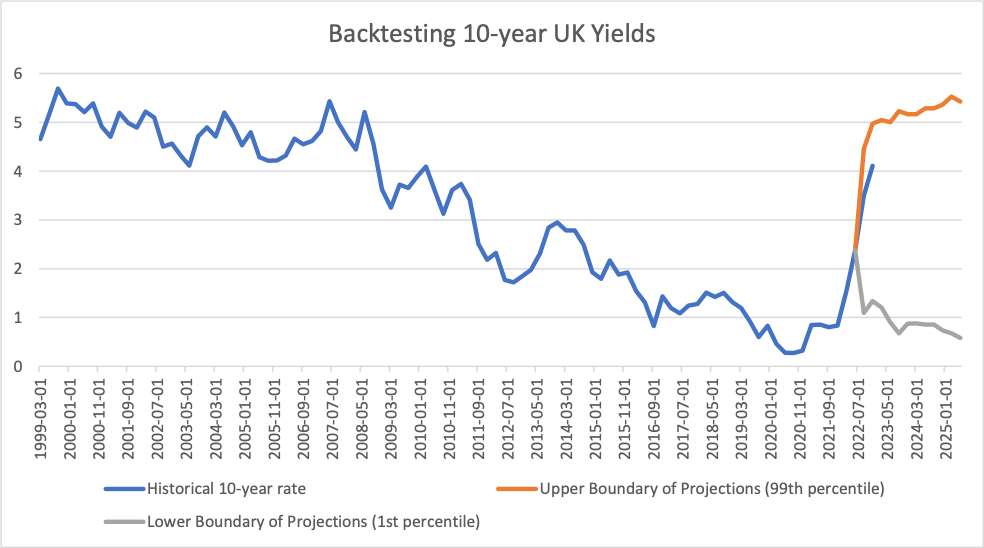

As shown in Figure 1, using only data through June 30, 2022, end-of-September scenario projections for the 99th percentile of the 10-year Gilt (i.e., U.K. government bonds) were as high as 4.4%. However, as we now know, U.K. government bond yields actually sat at 3.5% (the 87th percentile of yields distribution) as of the end of September.

Figure 1: Projections for U.K. Long-Term Government Bond Yields

Over the past 20 years, risk managers had the data necessary to be prepared for the probabilities/outcomes depicted in Figure 1. The stakeholders of U.K. pension industry therefore should have been ready for both a sharp increase in interest rates and the crisis that ultimately followed. Indeed, given the composition of the liquidity cushion, they should have realized that selling government bonds to cover margin calls would cause this perfect storm.

Evolution of LDI

LDI strategies were introduced about 25 years ago, around the same time as risk budgeting – a process through which a firm can identify the contribution of various asset segments to its overall risk.

Some experts contend that LDI does not actually reduce pension funds' risk, and that it’s used primarily as a tool to pass regulatory evaluations and to meet accounting standards. They further argue that the entire approach is flawed, because it’s not driven by the real market exposure. But this is a short-sighted view.

Even though underfunded pension schemes can pay liability cashflows for a while, these ongoing payments eat into their asset base, reducing their growth prospects and the chances of improving the funded ratio. Under such circumstance, the funded status deficit eventually does turn into a real cashflow problem.

Throughout the 1990s, pension funds held around 70% in equities and 30% in fixed income, and enjoyed a substantial surplus in their funded status. In early 2000s, however, things began to change.

When interest rates fell sharply, maintaining funded status became a constant struggle: even if assets performed strongly, low rates would prevent a fund’s recovery. When interest rates are on a rising cycle, funded ratios should become healthier.

Parting Thoughts

While most pension funds are not as leveraged as the U.K. funds were, there is still a need for the introduction of much more rigorous stress testing across a wide variety of market environments.

The critics who say that U.K. pension funds misused LDI may be right. But there is one solution that could have addressed all of the problems that arose: running an investment strategy through a full range of scenarios.

It is critical to understand potential exposures and mitigate them before it’s too late. Instead of banning leverage altogether in pension investments, there should be much better-defined stress testing to discover potential hidden pockets of risk and to identify appropriate actions.

Alla Gil is co-founder and CEO of Straterix, which provides unique scenario tools for strategic planning and risk management. Prior to forming Straterix, Gil was the global head of Strategic Advisory at Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, and Nomura, where she advised financial institutions and corporations on stress testing, economic capital, ALM, long-term risk projections and optimal capital allocation.

Topics: Investment Management