From Lebanon to Tunisia, from Ethiopia to Syria to Myanmar, political and humanitarian crises are flaring up worldwide, destabilizing economies amid a backdrop of social unrest and vaccination shortages in low-income countries.

Yet, in contrast to past eras, major banks are not imperiled by exposure to troubled international markets and their debts, and, given institutions' balance-sheet strengths and risk profiles, they are not setting off alarms about global financial stability. The Federal Reserve's most recent Financial Stability Report, in May, underlined such near-term concerns as setbacks due to coronavirus variants and, specific to emerging market economies, “difficulties in containing the virus, a possible further rise in long-term interest rates [affecting debt-servicing costs], and waning fiscal capacity.” Emerging-market stress was one of the least-cited risks in the Fed's outreach to market contacts.

The global financial crisis of 2008-'09 set the stage for international banks' current positioning. They pulled back from, and became more selective in, exposure to emerging economies. According to Zubair Iqbal, a former International Monetary Fund economist now with the Middle East Institute, countries like Lebanon, Tunisia and Myanmar did not fall in the category of newly emerging economies.

Reason for Retreat

“Exposure in most international markets was refocused on partnership with local banks for lending to the government and major private investors,” Iqbal said. American banks have since reduced their exposure in these countries, except, in some cases, in loans and guarantees in collaboration with domestic counterparts. “This strategy has sharpened since the advent of the coronavirus and global contraction in 2020,” Iqbal added.

The ongoing emergency in Lebanon was preceded by what Iqbal calls - and what lenders regarded as - an unsustainable “national Ponzi scheme” in which the central bank's “primary focus was on attracting foreign deposits to finance the balance-of-payment and budget deficits.”

The oil-rich Gulf countries lost interest in Lebanon for the same reason, Iqbal says, and the decline in oil income coincided with the emergence of other trouble spots in Iran, Libya, Syria and Yemen.

“Institutional Weaknesses”

The Lebanese economy is estimated to have contracted by 26% in 2020 and is likely to decline another 7% this year. The currency, the pound, has collapsed, and more than 70% of the increasingly pessimistic population is financially struggling. The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) concluded 82% are “living in multidimensional poverty.”

“Over the past year, we have been available for the Lebanese authorities,” International Monetary Fund managing director Kristalina Georgieva said in August, “but let me be very honest: Engagement is severely constrained by the absence of an effective government.”

Reporting on the September 10 installation of Prime Minister Najib Mikati, after 13 months of uncertainty, the New York Times noted that “the World Bank has said [Lebanon's economic collapse] could rank among the three worst in the world since the mid-1800s.”

Garbis Iradian, chief economist, MENA at the Institute of International Finance, said the conditions reflect “fundamental political-economic factors and institutional weaknesses. Such factors were exacerbated by the massive explosion that ripped through Port of Beirut on August 4, 2020, which killed more than 200 people and destroyed large part of the capital.”

Iradian said Lebanon's economic performance in the past few years has been the worst in its region, followed by Yemen.

Fitch Ratings affirmed Lebanon's long-term foreign currency Issuer Default Rating at “Restricted Default” and the country's long-term local currency at CC. While the official rate, at 1507 pounds to the dollar, has been fixed since 1998, the parallel exchange rate had depreciated to an average of 19,000 in August 2021.

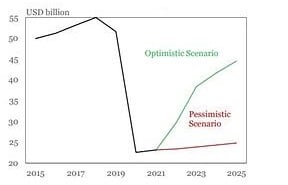

Triple-digit inflation resulted from a 90% decline in the currency valuation in less than two years, IIF's Iradian said in a mid-September report titled Cautious Optimism but Daunting Challenges. Under his optimistic scenario, “based on reforms and agreement with the IMF, the parallel exchange rate could continue gaining value to around 12,000 by end-2021.”

“The acceleration of the annual CPI inflation rate, from 11% in February 2020 to 190% in July 2021, is largely driven by the depreciation of the parallel market rate,” Iradian previously explained. “Available official reserves are depleting, and the central bank will not be able to continue subsidizing the imported cost of essential goods, including fuel, medicine and wheat.”

Less Contagion Risk

Along with banks' improved capitalization and modified emerging-markets exposure, “there has also been a reduction in contagion risk across emerging economies, as investors have become less exposed to certain EM regions,” said Rachel Ziemba, adjunct senior fellow, Center for a New American Security. This contrasts with some jitters set off by China's Evergrande.

“U.S. banking supervisors routinely question lenders about their ties to struggling companies,” said a September 28 Bloomberg report. “Fed Chair Jerome Powell said last week that 'there's not a direct United States exposure' [to Evergrande], adding that big Chinese banks also are “not tremendously exposed.'”

Lower EM debt/FX contagion risk stems from a reduction in currency pegs and unsustainable currency regimes among emerging and frontier economies. Those that keep their pegs, such as the Gulf states, mostly have sufficient reserves. Ziemba also noted improvements in external balances due to weak growth and net export adjustments. With a few exceptions, the risk of crises is much lower than it was five to 10 years ago.

Lebanon, Tunisia and Myanmar, among others, simply do not pose meaningful balance-sheet risk for major global banks. “In that way,” Ziemba said, “the global financial system insulation to these smaller jurisdictions has been increasing over time.”

“What has also changed,” she added, “is that there is more knowledge about balance-sheet risks, a more supportive global central bank environment, and thus less concern about the sort of off-balance-sheet risks and shadow banking system risks that were present in 2009-'10.”

While Lebanon's economy and debt had been looking questionable for years, banks tended to be exposed via their customers and avoided taking risks on their balance sheets. “Companies like Citi targeted their retail and business banking services to more-open financial jurisdictions and growing regions like the Gulf,” Ziemba said. “Even business banking services tended to be shuttered in the last few years as global banks focused on core jurisdictions. These trends reinforced a broader move away from their smaller jurisdictions.”