The failures of regional banks earlier this year brought renewed attention to held-to-maturity (HTM) assets and to arguments to eliminate the classification in favor of fair value accounting.

In an April 27 letter, the Council of Institutional Investors (CII) asked the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) to consider eliminating HTM for debt securities “and to improve financial instrument disclosures about liquidity risk and interest rate risk.”

The council pointed out that Silicon Valley Bank, in accordance with current accounting standards, disclosed in footnotes that $90 billion in HTM assets had $15 billion in unrealized losses, which nearly equaled SVB’s $16 billion in equity. However, audited financial-statement footnotes did not explicitly disclose any information about liquidity risk and had limited data on interest rate risk.

“In our view,” said the letter signed by CII general council Jeffrey Mahoney, “the financial accounting and reporting was clearly not the cause of SVB’s collapse, but its failure raises legitimate questions about the appropriateness of certain provisions of FASB standards” relating to HTM debt securities and the lack of risk disclosures in footnotes.

CFA’s Sandy Peters: Loss “hidden in plain sight.”

CII named supporters of its long-held position on HTM ranging from Warren Buffett to Fifth Third Bancorp CEO Timothy Spence to CFA Institute head of financial reporting policy Sandy Peters. In a blog dated three days after SVB’s March 10 closure, reiterating CFA’s longtime fair-value advocacy, Peters quoted herself from a 2009 New York Times article: “The purpose of financial reporting is to convey the results of the company. It is not to assure the company stays around.”

Peters said in a recent interview that under political pressure after the Great Financial Crisis, FASB retreated from a 2010 proposal, which CFA supported, that would have required banks to record nearly all financial instruments at fair value.

Where Banks Stand

Banking industry representatives argue instead that fair value is not appropriate for loans and securities such as Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, which banks hold to collect income streams. Josh Stein, vice president, accounting and financial management, American Bankers Association, said that to understand a bank’s capital adequacy and performance, the key concern is credit risk rather than interest rate volatility, because the latter does not directly impact cash inflows and outflows.

Stein said a comment letter on FASB’s 2010 proposal from top banking regulators reflects the ABA’s stance on HTM. “In our view,” they said, “the accounting for financial instruments should reflect a financial institution’s business strategy and the manner in which cash flows will be realized or expended.”

That letter described fair value accounting as appropriate for trading activities and derivative instruments but “generally not appropriate for financial instruments held for collection or payment purposes.”

Nevertheless, some bankers agree that changes are due. Brent Beardall, president and CEO of $21 billion-in-assets Washington Federal Bank in Seattle, contends FASB should consider requiring balance sheets to be presented at amortized cost and at fair value, so that the information is comparable across all classes of assets and liabilities.

“The benefit of amortized cost is that you know where a willing buyer meets a willing seller,” he said, adding that while fair value provides the current status of a balance sheet, it can be distorted by market occurrences such as distressed sale and is derived from models. “If there’s anything we’ve learned from Silicon Valley Bank, it’s that models can be wrong.”

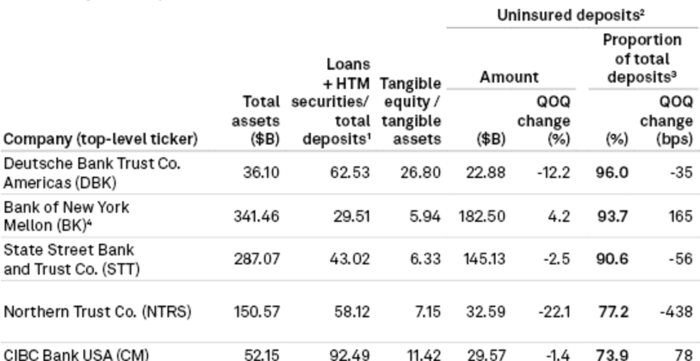

Of the 25 biggest U.S. banks, ranked by proportion of uninsured deposits in a June 12 S&P Global Market Intelligence report, BNY Mellon was lowest in loans and held-to-maturity securities as a percentage of total deposits. “Accounting rules do not require banks to mark the HTM portfolios to market, but regulators have openly worried about the capital hits banks would take if they were forced to sell underwater securities in a time of stress,” the S&P analysis said.

No Official Movement

The FASB and Securities and Exchange Commission have thus far shown little inclination to change current financial-instrument accounting. Bloomberg reported in March that SEC chief accountant Paul Munter pushed back on calls to reopen the HTM debate by saying investors currently have sufficient tools.

Asked by GARP Risk Intelligence if FASB has a response to the CII letter, a spokesperson said, “As with all agenda requests, the FASB will review and consider it as part of our process.”

Proponents of HTM say that fair value information is already in financial statements. Peters of CFA countered that fair value is disclosed only on the face of the financial statement and in footnotes, and any unrealized loss is “hidden in plain sight.”

Tom Linsmeier, a former FASB board member who supported the 2010 FASB proposal and is now department chair of accounting and information systems at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, explained that investors and risk managers are more likely to use data aggregators to populate their systems than go to banks’ 10-K filings. Asset carrying amounts provided by regulators for HTM securities are at amortized cost, making it harder to get the fair value information necessary to understand interest rate risk, he said.

Prof. Tom Linsmeier: Footnoted data is delayed.

The only fair value information for HTM securities is usually in financial statement footnotes, and with a delay because preliminary earnings releases typically reflect the statements but not the footnotes. “So the risk manager will have to take additional steps after the preliminary earnings release to get the fair value information necessary to understand interest-rate risk and its effect on that class of instruments,” Linsmeier said.

Digging Out the Data

A complete understanding of interest rate risk requires an accounting of all financial assets and liabilities at fair value, the Wisconsin professor noted, but reporting just HTM assets at fair value could have benefited investors in SVB.

“If market participants do not dig into the footnotes to understand the fair-value volatility that is hidden in the notes, there is less incentive for bankers to pay attention to the problems as quickly as they would have if their asset carrying amounts changed as interest rates changed,” Linsmeier said.

He added that earlier recognition of the potential peril from interest rate changes could have prompted SVB management to take steps sooner to bolster capital, such as eliminating dividend payments, issuing debt, incrementally selling available-for-sale securities, even shortening the duration of assets.

“They could have started managing interest rate and deposit-flight risk sooner, but the accounting allowed them to keep their heads in the sand because the numbers recognized in the balance sheet and income statement were not making them accountable for what was happening on a timely basis,” Linsmeier said. “The fair value information was there. It just wasn’t in plain sight nor provided on a timely basis.”

In a blog on the SVB and First Republic Bank failures, Larry Wall of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Center for Financial Innovation and Stability wrote that “the argument against recognizing losses appears strongest when it is least important: when interest rate changes are relatively small as the deposits are less likely to leave. However, the argument is most likely to fail when measuring values accurately is most important, which is in response to large interest rate movements when depositors are likely to withdraw their funds . . .

“Although deposit runs forced SVB and FRCB into resolution, the (market value) losses started with rate increases in 2022, and the losses exceeded book capital by the third-quarter 2022 financial statements. Yet the banks did not become candidates for resolution until after their depositors started to run.”

According to aggregate data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., banks’ unrealized losses on investment securities declined to $515.5 billion in the first quarter, from $617.8 billion at the end of 2022.

Topics: Market