Even before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, country risk was already a top concern facing manufacturers, retailers and financial institutions. Estimating this risk, however, entails far more than predicting whether a foreign country might default on its sovereign debt or whether foreign currency might depreciate.

Indeed, the risk of doing business in a foreign country includes everything from the reliability of supply chains to the availability of sources of capital to ongoing access to customers and the potential expropriation of investments.

Risk managers today need to rely on multiple sources of information to capture both the quantitative and qualitative aspects of country risk. Data-driven risk assessments – combined with the research of country analysts who put information into context – can generate a more reliable and complete picture of short- and long-term country risk than any single source.

Glimpsing History to Better Understand the Future

Despite the recent attention, country risk management is nothing new. International trade and closer economic integration between countries is attractive, as it can bring enormous benefits in the forms of greater efficiency and comparative advantage. But if dependencies between countries develop and relations fray, trade can also pose risk.

Following World War II, shared mutual interests between countries were so strong that the possibility of reversing the globalization trend seemed remote. However, those closer trading relationships were arguably so successful that nations eventually became complacent. What’s more – as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and heightened geopolitical tensions in Asia – that complacency has been exposed.

Germany is perhaps the quintessential example of a country that sought to optimize all aspects of its economy through trade, having outsourced much of its energy production to Russia; its military defense to the United States and NATO; its monetary policy to the European Central Bank; and its export-driven economy to China. While those policies yielded great benefits, they also increased Germany’s vulnerability to shocks.

Globalization may not be dead as a result of the events of the past two years, but it will be more limited in scope, and companies will place greater emphasis on resilience going forward.

Evaluating Short- and Long-Term Threats: The Importance of Data

A critical component of international investment and development is the risk associated with doing business in a foreign country. Recent experience has emphasized the need for companies to take a systematic approach in measuring and managing these risks in a consistent and accessible manner.

Cristian deRitis

To meet this objective and the needs of risk managers, our research has sought to assess a variety of threats to countries across the globe. The key pain point in this research is data: quality, reporting lags, and availability.

One way to categorize country risks is by forecast horizon. Predicting the probability of a recession or currency devaluation in the near-term, for example, is not only a relevant time frame for action but also for predictive power. High-quality data surrounding these specific near-term risk events are readily available, which allows for timely, high-frequency estimates.

In contrast, climate change and social unrest have significant consequences, but can take a long time to materialize. In addition, the data surrounding these risks are infrequently measured and harder to find. As a result, longer-run risks are more easily classified into broad over-arching risks.

Fundamental Indicators: Building a Framework

The risk landscape is always changing. While some threats are novel, such as cybersecurity, others just shift in focus.

For example, in the late 1990s, the Asian currency crisis focused our attention on economic and financial contagion. We are still focused on interdependencies today – but through the lens of global supply chains and environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations.

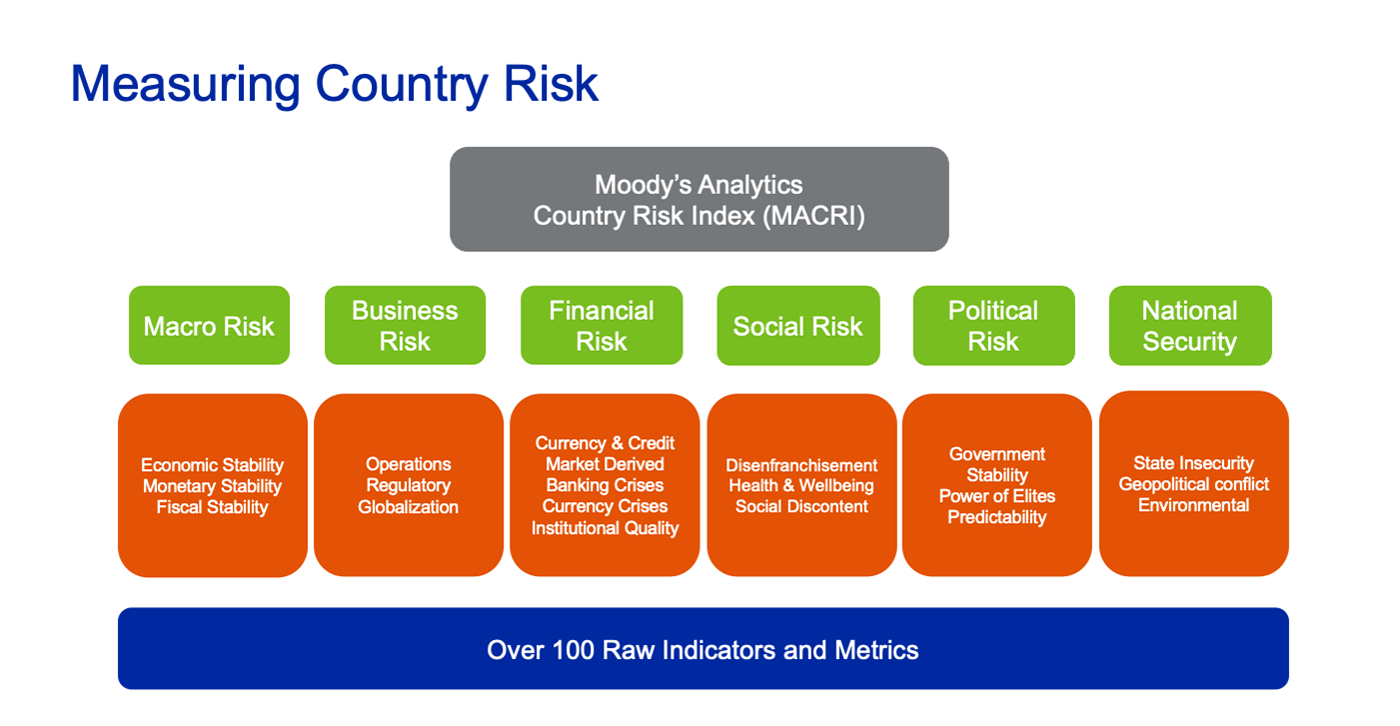

Figure 1: A Six-Pronged Country Risk Framework

While we need to account for emergent risks, we have found that many country risks have overlapping underlying indicators. Contagion, for example, depends on currency stability – but so does transfer risk. Terrorism and modern slavery, moreover, have many of the same fundamental drivers.

Given these observations, our framework (see Figure 1) groups country risks into six fundamental categories:

- Macroeconomic risk. Threats stemming from the natural cyclicality of the economy and the quality of a country’s monetary and fiscal policy.

- Business risk. Operational uncertainty from local conditions that businesses face daily.

- Financial risk. Possible shifts in asset and liability valuations, because of interest-rate and exchange-rate shocks.

- Social risk. Large-scale social upheaval or individual-level risks, such as crime and disease affecting human resources.

- Political risk. Policy uncertainty and/or the possibility of large shifts in political conditions.

- Security risk. Dangers to human life and property from war, geopolitical instability, natural disasters, and climate change.

Riskiness Is in the Eye of the Beholder

There is considerable value to identifying, measuring and understanding each of these six risk categories for a given country. However, scorecards that combine all risk elements together into a single measure are operationally useful, particularly for risk managers charged with assessing risks across multiple geographic jurisdictions.

The question then becomes, how should we weight these various factors?

As with most risk assessment algorithms, there is no single “best” solution. A formal modeling approach might estimate the relative importance of each of the six measures in explaining historical risk events or expected default frequencies.

Though quantitatively appealing, this approach may be too generic for the specific risks facing a given firm. For example, a company may wish to assess country risk for the purpose of determining where to locate a manufacturing facility. Under such a scenario, we might place greater weight on business risk or security risk than political risk.

Exposing metrics on each of the six risk categories, by country, allows risk managers to adjust weights to produce scores that most accurately match their risk preferences.

Parting Thoughts

Given recent events and the heightened awareness of regulators and stakeholders, country risk will surely increase in importance going forward.

For an individual firm, the benefits of a comprehensive country risk program include the following: (1) improved decision-making when expanding or managing business operations in another country; (2) a better-informed investment strategy, thanks to comprehensive insight into risk factors within and across countries; (3) more stringent compliance with regulatory requirements, resulting from country monitoring that informs limit setting when lending overseas; and (4) enhanced supply-chain management, through assessment of countries’ ability to manage shocks.

While risk tolerances undoubtedly vary across industry segments, even individual companies within the same industry will have different exposures and priorities. Consequently, more important than the actual data measuring the various components of country risk is the design framework. With a clear, consistent framework, stakeholders can focus on the specific aspects of country risk that are most relevant to their institution or objective.

Considering data limitations and the speed at which global markets change, measuring and managing country risk is particularly challenging. But the flexible framework we’ve outlined at least provides a starting point for more constructive conversations surrounding country risk. These discussions can evolve, and firms can adapt, as data availability and risk priorities change.

Cristian deRitis is the Deputy Chief Economist at Moody's Analytics. As the head of model research and development, he specializes in the analysis of current and future economic conditions, consumer credit markets and housing. Before joining Moody's Analytics, he worked for Fannie Mae. In addition to his published research, Cristian is named on two U.S. patents for credit modeling techniques. He can be reached at cristian.deritis@moodys.com.

Eric Gaus is a Senior Economist at Moody’s Analytics. As part of the model development and maintenance team, he manages the company’s country risk service. Before joining Moody’s Analytics, he worked at Ursinus College and Haverford College, and published several articles on expectation formation within macroeconomic models. He can be reached at eric.gaus@moodys.com.

Topics: Metrics