From real estate debt to regulatory crackdowns to geopolitical tensions, China gives investors, risk managers and corporate strategists more than a few reasons to prepare for adverse outcomes or allocate resources elsewhere.

But the world’s second-biggest economy remains a business magnet. Citigroup, for one, amid a flurry of Asian initiatives, has opened a commercial bank China desk in Singapore and followed other Wall Street giants in applying for securities licenses on the mainland. Credit Suisse is targeting further expansion, and Bridgewater Associates recently raised $1.25 billion for its third China investment fund.

Bridgewater founder Ray Dalio said in a Yahoo Finance interview: “If trends continue, China will be stronger than the United States in the most important ways that an empire becomes dominant. Or at the very least, it will be a worthy competitor.” Ian Bremmer, president of political risk consulting firm Eurasia Group, told the same outlet that many CEOs of Western companies plan on “doing more business in China over the next 10 years, not less,” because the country is on track to being the largest economy by 2030, “and corporations ultimately want to be where their markets are going to be.”

All of this in the shadow of Evergrande Group, the real estate developer whose unsustainable $300 billion debt load threatened a crisis of confidence if not one of systemic or international contagion. A missed payment prompted Fitch Ratings on December 9 to downgrade Evergrande and its subsidiaries to “restricted default.” Yet despite months of dire headlines about Evergrande and others in its sector, damage to markets on the whole appears to have been contained.

Development Model Upended

“As a highly leveraged developer that veered into all kinds of non-core businesses, Evergrande had two strikes against it,” said TCW emerging markets group managing director David Loevinger. “But it was the decision to move away from a leverage- and property-driven growth model, which led to policies of three red lines for developers and two red lines for banks, which ultimately cut off Evergrande’s oxygen.”

“The traditional model of property development is no longer viable and must be changed, but the government must be very careful and understand it needs patient policy action for a soft landing,” said Xingdong (XD) Chen, chief China economist and head of macro research, BNP Paribas. “Both Premier Li Keqiang and [Vice Premier] Liu He have recently called for careful policy design, deep analysis and assessment of implication, and good communication with the market and stakeholders in market.”

Chen noted that the central bank and China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) “are now turning to urge commercial banks to extend rational loans for property investment, to increase mortgage loan quota and to allow those property developers with sound balance sheets to raise debt capital in the bond market.”

Bigger Picture

Any Chinese risk assessment must take into account factors ranging from COVID-19 waves to consumption and the service economy. “Retail sales of consumer goods rose by only 3.5% in two-year compound growth in nominal terms (or 2.5% in real terms) in the first 10 months [of 2021], compared to a usual 8% to 9% annual growth before the pandemic,” Chen said.

Property deleveraging and contraction pose additional risks. Policy measures such as property taxes have started to reverse development excesses.

“The property industry faces funding stress, both from sales and credit/debt financing,” Chen stated. “The industry has been the pivotal contributor to the economy, given it has long industrial chains related.”

According to BNP Paribas, property is estimated to account for 14% to 25% of GDP, depending on how it is calculated. Regardless, Chen said, “Property investment and housing consumption are the largest risks in predicting China growth in 2022. The forecast for property investment varies from growth of 2% to 3% to a decrease of 15% to 20%. We predict it to dive by 5%.”

Debt and Spillovers

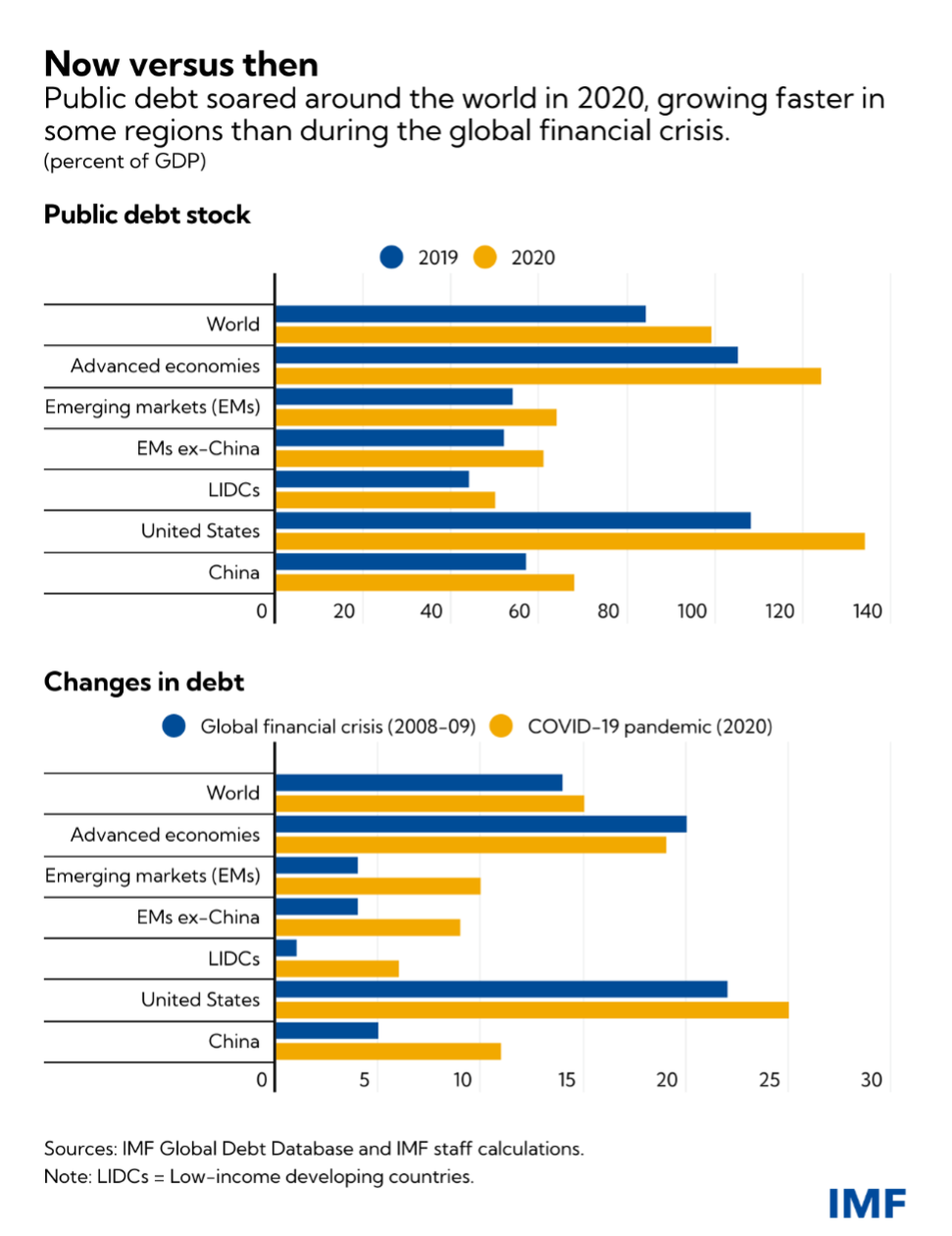

Developments in China have global risk monitors on alert. The International Monetary Fund, reporting on “the largest one-year debt surge since World War II, with global debt rising to $226 trillion” in 2020, found that “China alone accounted for 26% of the global debt surge.”

Citing Evergrande and other leverage issues, the Federal Reserve Board, in its November 2021 Financial Stability Report, said, “Stresses in China’s real estate sector could strain the Chinese financial system, with possible spillovers to the United States . . . Given the size of China’s economy and financial system as well as its extensive trade linkages with the rest of the world, financial stresses in China could strain global financial markets through a deterioration of risk sentiment, pose risks to global economic growth, and affect the United States.”

The Bank of England concluded in December that “global debt vulnerabilities remain material.” BOE considered the potential impact on the U.K. of a serious downturn in China stemming from high and rising debt levels, and said that a solvency stress test showed the U.K. banking system “is resilient to the direct effects of a severe downturn in China and Hong Kong, as well as indirect effects through sharp adjustments in global asset prices.”

As reported by Reuters, 37% of respondents to an Asia Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association survey expected the regulatory and operating environment in China to become more challenging in the next three years. (Forty-eight percent said the same about Hong Kong.) Yet 84% said they were expanding their operations on the mainland, and 54% in Hong Kong.

Investment risk is heightened by opaque data and policymaking and Communist Party influence over private enterprise. But according to TCW’s Loevinger, there are “underlying credit strengths, including a large, diversified economy and a resilient and globally competitive supply chain. We continue to see it as a solid A-rated sovereign credit.”

In the short term, risks are rising as China shifts away from a credit- and property-driven growth model,” Loevinger continued. The government appears intent on shrinking the number of companies viewed as too big to fail, “all of which should lead to more debt restructurings or bankruptcies,” he added.

A “Plus” Future

Chen said that although the property sector may see further balance-sheet deterioration, “given China’s political system, we still don’t see any systematic financial crisis.”

Loevinger said that China could emerge from this episode as more attractive for investors: “A financial system that has to price credit risks on fundamentals rather than expectations of bailouts will be more stable and supportive of growth.”

With the opening of financial markets, foreign investment has been pouring in, while China is now included, and has increased its weighting, in major stock and bond indices. “In a world of zero- and negative-yielding debt, China offers investment-grade government bonds, with relatively high yields and low volatility.” Loevinger said. “It’s a big market where trades can be done in size. And a large economy with its own economic cycle gives investors diversification.”

He said many foreign companies are adopting a “China plus” strategy, viewing the domestic market as just too big to leave or ignore. “But they are hedging against the risks of a less business-friendly environment and some decoupling with the U.S. by shifting some operations outside of China.”