From renewables to aviation to coal, COVID-19 has exposed both strengths and weaknesses among different sectors when it comes to climate issues. And the effects one may or may not have on each other are an emerging topic among risk managers around the world, both within large multinationals and niche firms that advise companies on carbon transition.

The pandemic and subsequent business interruption has led to a wave of downgrades and negative outlooks across asset classes, including environment, social and governance-driven assets (ESG). Moreover, it has resulted in trillions of dollars in public spending, loan guarantees and asset purchases by governments and central banks.

It has also raised the stakes for the use of public funds; governments, for example, that have made pledges under the Paris Agreement “are coming under intense pressure to ensure public money is not detrimental to low-carbon transition,” says David McNeil, associate director and ESG analyst with Fitch Ratings. “In addition, the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (UN PRI), with signatories representing over $86 trillion of assets under management, have already talked of an 'inevitable policy response' to climate change to be disrupted until the middle of the decade due to the growing gap between pledges and performance under the Paris Agreement.”

McNeil, who co-authored the April 29 report, Climate Risk and the Coronavirus Pandemic, explains that the pressure will only intensify in the coming months as countries publish their revised pledges.

Pierre-Francois-Thaler, co-founder and co-CEO of EcoVadis - a provider of business sustainability ratings and intelligence - draws similarities between the climate crisis and COVID-19. Both are global and ongoing, he says, and both are creating havoc, if not disruption, among millions of lives.

“The two are non-linear in the sense that 'socioeconomic impact grows disproportionately once certain thresholds are breached,'” says Thaler, referencing an April McKinsey report, Addressing Climate Change in a Post-Pandemic World. “Both are risk multipliers, exposing and emphasizing weaknesses in the financial and healthcare systems.” In addition to bringing significant warnings, he elaborates, both crises are “regressive, and disproportionately affecting the weakest among us.”

Another similarity is the cost of ignoring science, Thaler notes. “This has been demonstrated recently during the pandemic, but also over decades with climate change.” Thaler and analysts agree the most important effect COVID-19 will have on the fight against climate change is that it's brought awareness on the disruption climate crisis could bring to not only millions of people, but to business operations, supply chain and globalization and more. “In fact,” Thaler says, “it has accelerated the fight against climate change by showing firsthand how dire the impact could be.”

Managing the Fallout

Supply chain disruption has placed new scrutiny on the provenance of supply chains and to areas beyond pricing as companies seek to mitigate future risks. “Supply chains represent the bulk of carbon emissions for many industrial sectors, and are under increasing scrutiny from investors,” McNeill says. “But other environmental concerns, such as water scarcity, are increasingly likely to be on the agenda as physical risks of climate change take hold and threaten supply chains.”

In energy, there is a risk that marginal energy producers will suffer “if there is not a full rebound to previous levels of demand and coal generators 'competing in' merchant markets,” says James Leaton, a vice president in Moody's Investors Service's ESG group.

“North American oil producers have seen the largest shut-ins of production in both US shale and Canadian oil sands, aside from the OPEC+ agreed supply cuts,” Leaton elaborates, adding that the speed and extent of the recovery is “by no means certain for those that had previously been assuming it would be business as usual.”

A Mispricing of Risk

From hurricanes to devastating floods, the market has clearly been mispricing risk - both pandemic risk and climate risk. Companies today, according to McKinsey senior partners Matt Rogers and Hamid Samandari, have an opportunity to reduce both the physical and transition risks posed by climate change by integrating a systemic approach to climate risk management into decision making.

“Asset managers need to understand the climate risk in every asset in their portfolio,” Samandari says. “And companies need an 'asset-by-asset understanding' of physical risk and transition risk.” This would mean taking climate considerations into account when looking at capital allocation, operating standards, product development, and supply-chain management, among other areas.

“Governments need to understand the economic impact to physical infrastructure damage that could hurt long-term economic growth and recovery,” Samandari continues. “Investments in infrastructure resilience today are much cheaper than rebuilding after a disaster.”

The pandemic has underscored the fact that tail risks can have rapid and devastating impacts when they do materialize, and that investing in preparedness is well worth the effort. Emilie Mazzacurati, founder and chief executive officer of the Moody's affiliate Four Twenty Seven - a provider of climate risk data and analysis - says that the pandemic represents an example of what an “abrupt, disorderly transition away from fossil fuels may look like.”

Nearly overnight, she says, “factories closed, airlines were grounded, and travel ceased.” The industries affected by this response (such as airlines, automotive and ground transportation) - were, moreover, exposed to transition risk. These events, Mazzacurati elaborates, should “inform risk assessment and scenario analysis for climate change” in the future, helping, risk managers rethink what might be possible.

From a risk perspective, weak or misdirected policies on climate transition today mean the climb in the future will be much steeper. “The PRI has examined climate-related policy scenarios and sees that the mid-2020s are already likely to involve disruptive climate policies,” says Nathan Fabian, chief responsible investment officer of the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI). “Misdirected pandemic recovery policies increase that likelihood.”

A Welcome Downturn

The short-term impacts of COVID-19 on climate risk manifested as a large temporary reduction in emissions, estimated at 17 percent globally. Factory shutdowns and decreased transportation has led to a significant drop in the global production and consumption of both coal and oil, but the more prominent question is about the long-term impacts, which are less clear. “In the event that we have a V-shaped recovery, returning to 'normal' in a few months, the structural drivers of emissions will remain, and emissions will rebound,” Mazzacurati said.

The pandemic could also lead to long-term shifts in how business is carried out, with less travel and more remote work. This, Mazzacurati explains, would have more lasting impacts on greenhouse gas emissions, which would affect the climate change trajectory but certainly not eliminate effects.

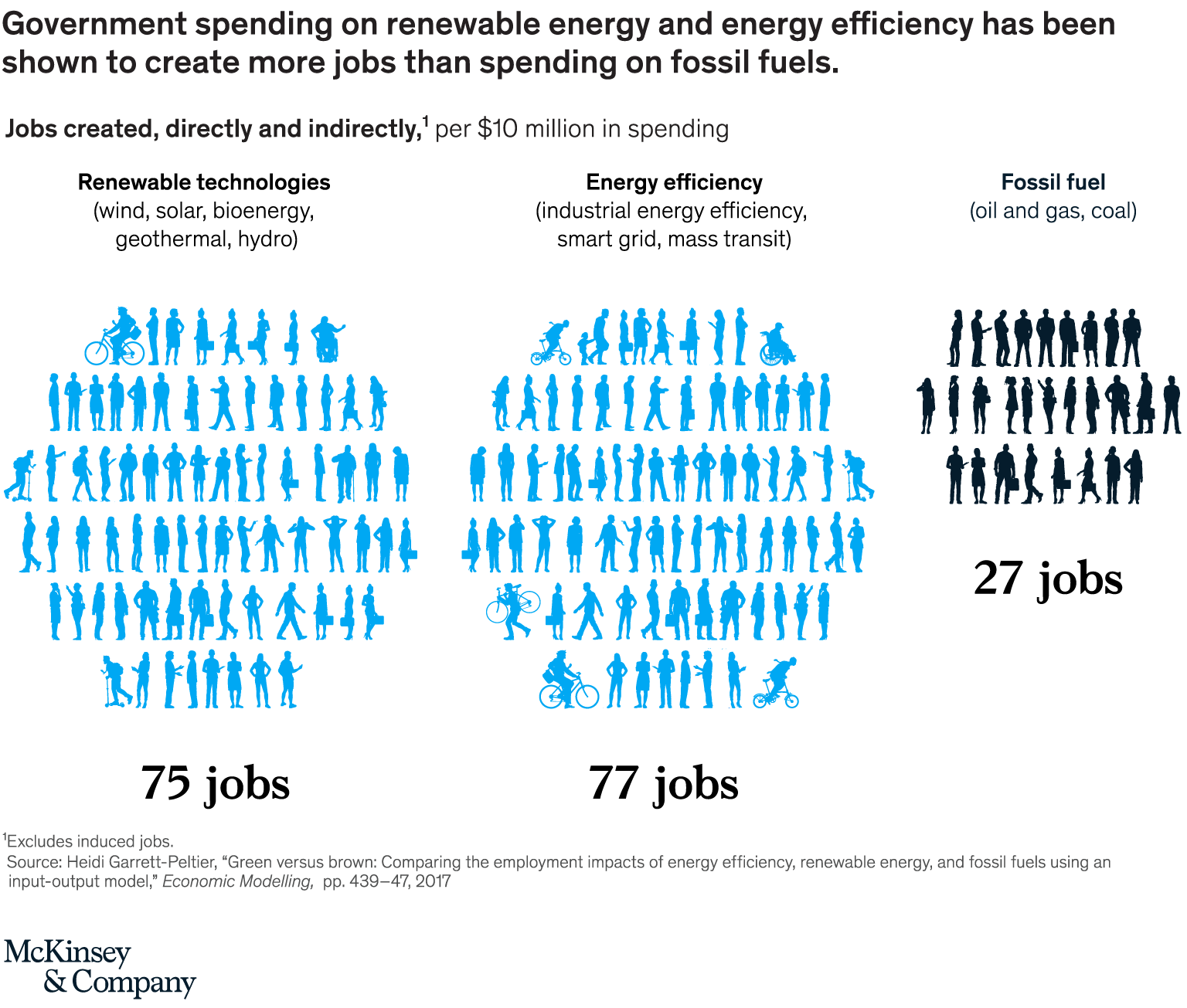

Recovery agendas and policies will have a large impact on the long-term implications for climate change. “If governments use this as an opportunity to support green jobs and technology in line with a transition away from fossil fuels, there will be a larger chance of a longer-term trajectory towards reducing climate change,” she says.

In terms of emissions, the pandemic is a welcome downturn, but cumulative emissions over decades are what determine warming levels. “Pre-COVID, it was clear that there was significant investment required to decarbonize economies,” Moody's' Leaton notes. “And this need has not gone away.”

In some countries, there are signs that government spending could be directed toward green infrastructure, or that improved carbon efficiency could be attached to bailouts for sectors such as airlines or autos in France or a Green New Deal within the European Union. Germany, for example, recently announced a $145 billion stimulus package that included major support to electric vehicles and charging infrastructure, but nothing for conventional car manufacturing, signaling a continued push toward a low-carbon transition.

In contrast to 2009, when economic stimulus measures were heavily channeled to coal and a 'brown recovery,' renewable energy sources are at or close to price competitiveness. In key developed and emerging markets, McNeill says, the crisis is likely to exacerbate financial challenges for thermal coal projects in many regions. “The big uncertainty is in China, where a gradual push to address coal overcapacity, merge state-owned enterprises and close some plants early could fall victim to short-term pressures to support regional growth,” he says, adding that China's coming 'five-year-plan' will be a clear indication of intent with regards to energy transition when published.

Fitch's approach, according to McNeill, is rooted in providing clear and transparent guidance in the form of ESG Relevance Scores, which are forward-looking and integrated into the research process. “Despite the range of downgrades and negative outlooks that have occurred since the outset of the crisis, none of these to date are attributable to climate-related factors, although the crisis will likely place more pressure on sectors already struggling with the costs of low-carbon transition, such as steelmakers and auto producers in the EMEA region.”

What Lies Ahead

Ultimately, the global economy can emerge cleaner and more resilient - or the COVID-19 pandemic can delay impactful climate action. A lot of marginal activity has been knocked out that may never come back - high pollution and low value creation, for example. Moreover, temporary adjustments such as teleworking and greater reliance on digital channels may reduce emissions permanently.

On the other hand, low oil prices could further delay clean energy transitions. “And, if China is any guide, riding public transit is unlikely to return quickly, so traffic congestion is back with a vengeance,” McKinsey's Rogers says.

The $10 trillion in stimulus measures that policy makers have allocated to date could be spent to accelerate climate action. Otherwise, “we risk going from one crisis to the next,” Rogers adds.

The good news, he explains, is that investments in climate-resilient infrastructure and the transition to a lower-carbon future could drive significant near-term job creation while simultaneously increasing economic and environmental resiliency. “Policy makers and business leaders can plan for much greater economic and environmental resiliency as part of the recovery ahead.”