If you Google 'stress test,' you'll most likely see a person on a treadmill, hooked up to electrodes, with an ECG monitoring his or her heart. A stress test for a financial institution is similar: it puts the firm through an extreme scenario and tests whether it is healthy enough to withstand the stress.

From a risk management point of view, stress testing is a good thing. It's forward-looking and provides insights into the riskiness of a bank in a way that is impossible using static financial accounting data. Moreover, when done at an enterprise level, it brings together different disciplines within a bank (e.g., risk and finance) to look at their business in a holistic way.

Banks, however, remain subject to a glut of stress tests: exercises that ask for a variety of information in a variety of formats at a variety of times. Results, therefore, cannot be easily compared across jurisdictions, and the lack of coordination between regulators is heaping greater demands on banks.

Supervisors can potentially remedy these issues by creating an agenda for developing more harmonization across stress tests. A common set of standards would benefit banks and regulators alike, helping to build a more resilient financial system.

Often, the conversations stress tests yield are as useful as the numbers themselves. A bank's board should never, in fact, sign off on the corporate plan until they see how it behaves under stress.

But banks haven't always proved very good at this. In the run up to the financial crisis, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) found that banks' stress testing practices were severely deficient, being poorly executed and neither sufficiently comprehensive nor severe. Consequently, they created a set of principles to guide banks and supervisors on how to organize and execute stress testing.

These Stress Testing Principles, recently updated, remain as pertinent now as they were in 2009. It's hard to argue against them - indeed, they are excellent.

Stress tests, according to the BCBS, must (1) have clear objectives and be effectively governed; (2) be used by banks as a risk management tool to inform business decisions; (3) cover material and relevant risks; and (4) be based on scenarios that are sufficiently severe.

The principles also note that the stress testing process should be built on a foundation of sufficiently granular data and robust IT and that the models and methodologies used in stress testing must be fit for purpose. Furthermore, stress testing practices and findings should be communicated between authorities/supervisors, both within and across jurisdictions.

So, how close are we to achieving these objectives? Certainly, stress testing has come a long way since that first Basel report. Banks have spent an enormous amount of money improving all aspects of their stress testing, including modeling, data, governance and execution.

But the most striking development has been the intensification and proliferation of supervisory stress testing both across and even within jurisdictions, each with its own approach and operating details. The most resource intensive of these are the so-called concurrent capital exercises - such as those run by the Fed, the European Banking Authority (EBA) and the Bank of England (BoE) - where multiple banks must run the same scenario at the same time.

Global banks operating in multiple jurisdictions have felt the brunt of this, spending a great deal of resources to meet multiple uncoordinated demands across different regulators. Even beyond this inefficiency, there are some undesirable consequences for both supervision and risk management.

Negative Ramifications of the Lack of Coordination and Harmonization

The fact that supervisory stress tests are on completely different bases makes them extremely hard to compare and, more importantly, undermines the supervisors' ability to communicate with each other about the risks that they see in their jurisdictions. The differences are too numerous to cover in detail, but we can offer a few examples.

Stress-testing scenarios cover different horizons, from nine quarters (CCAR) to three years (EBA) to five years (BoE). Each test, moreover, rests on different assumptions about how the firms' balances evolve in response to stress: prescribed lending paths (BoE), static balance sheet (EBA) and constant or no prescription (CCAR, depending on whether the stress test is company-run or modeled by the Fed) are among the various approaches.

The EBA takes things a step further by building in many constraints (such as various caps and floors) that do not feature in other tests. What's more, the treatment of management actions and hurdle rates differ across the tests. Indeed, it is probably easier to say how the tests differ than how they are similar.

The final Basel principle encourages the sharing of results and insights across supervisors, but this inability to 'join the dots' between stress tests is a missed opportunity; in an increasingly dynamic and interconnected world, supervisors need to able to understand the risks across institutions and at a systemic level.

As each stress test has its own instructions/templates/methodology, banks are in danger of focusing more on template filling than on the risk insights from the stress tests. Accordingly, stress testing becomes a compliance exercise, rather than a risk management exercise

The scale of documentation required, and the granularity of projections asked for, is often very high. What's more, the resources that are spent on these template-filling exercises are then not available for stress testing for firms' internal risk management; the regulators, in effect, 'crowd out' risk management, with firms then using the regulators' scenarios rather than designing their own.

Overall, there are higher costs and a lower quality of outputs for both banks and supervisors than if there was better coordination and better harmonization of approaches across regulators.

Common Sense Advice: Starting a Dialogue

The purpose of stress testing, of course, is to see how resilient firms are in the face of stress. We must not forget, however, that any exercise that involves looking into the future is inherently uncertain.

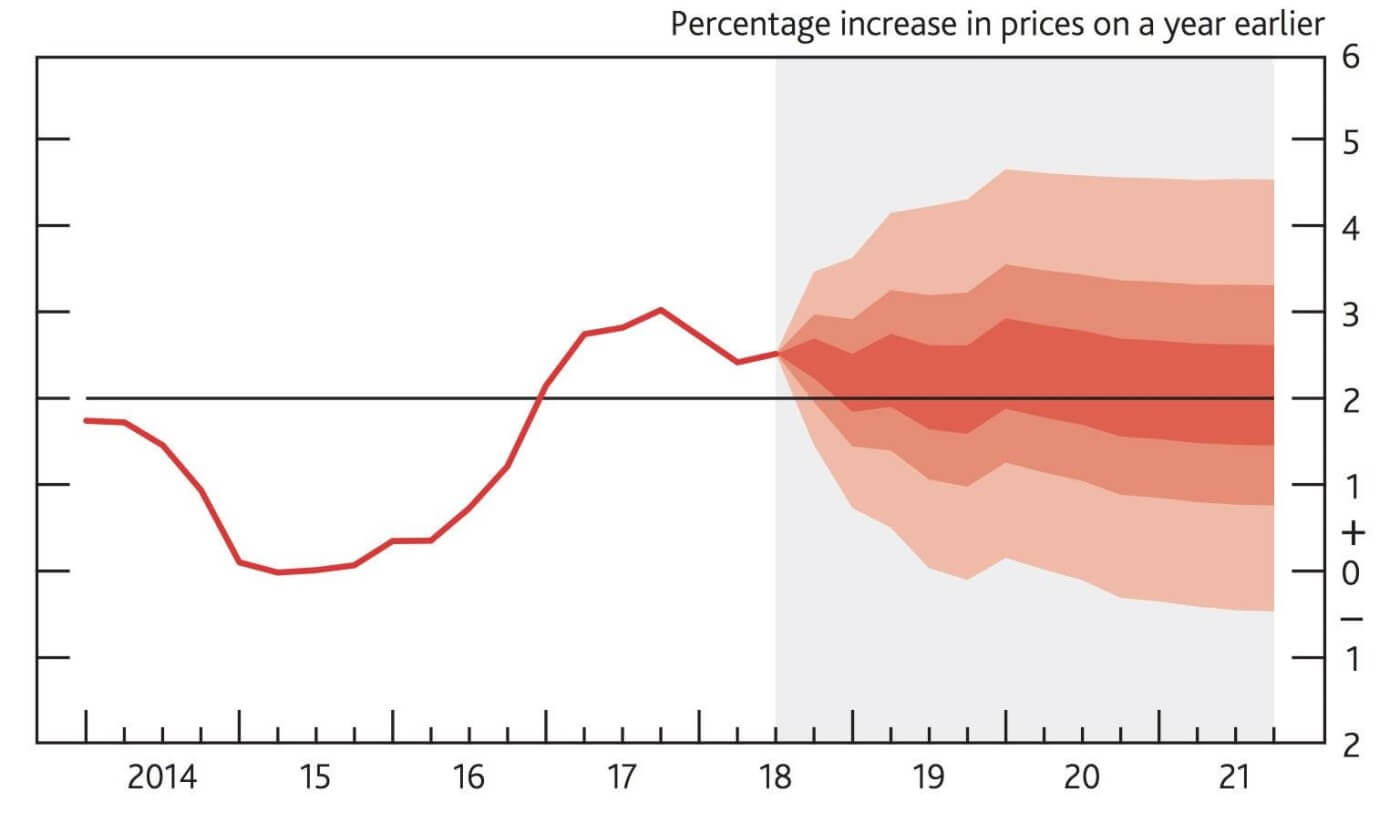

Take, for example, the significant range of uncertainty (even at a two-year horizon) in the Bank of England's inflation projection 'fan chart.' That chart, keep in mind, is for a projection of something that we expect to happen.

Chart: CPI Inflation Project

Forecasting the impact of extreme events is even more uncertain, as there may be little history to act as a guide. Indeed, the fan chart on a stress test would be enormous.

So, we think it's time to inject a bit more common sense and order into the world of stress testing. Recently, the GARP Risk Institute published a Code of Practice for Supervisory Stress Testing that provides a framework to promote the coordination and harmonization of supervisory stress tests.

The goal is to start a dialogue between risk practitioners and regulators. But how can this be accomplished? We have a few ideas.

For starters, supervisors could publish the schedule for the stress tests that they intend to run and discuss this at the college of supervisors. This would help banks facing multiple supervisory demands to plan their resources accordingly. Of course, it's up to regulators themselves to plot the best course with respect to harmonizing their regimes; Basel could play a role in coordinating a global calendar.

Supervisors should also be wary of requiring highly-granular projections, which arguably raise the risk of banks being 'precisely wrong' rather than 'roughly right.' The granularity required for regulatory stress tests should be set with consideration to the materiality of the risks, the time horizon of the projections required and the costs and benefits involved.

Furthermore, supervisors should create an agenda for developing more harmonization across stress tests. Greater harmonization could (1) aid the exchange of information between supervisors, as the tests would be more directly comparable; (2) give banks the ability to produce the information more efficiently; (3) improve the quality of the outputs; (4) encourage greater investment in strategic IT infrastructure; and (5) help investors and analysts who need to interpret the results of different stress tests.

Almost as important as the steps firms should take is what they should avoid. To a certain extent, stress testing is educated guess work, so banks and regulators should not take comfort from asking for an inordinate amount of documentation. Since plausibility and reasonableness is probably the most one can hope for, it also doesn't make sense to talk about 'accuracy' of projections.

Parting Thoughts

Today, many regulators, including the BoE, the Fed and the EBA, are reviewing their approach to concurrent stress testing in the light of lessons learned. It's therefore a good opportunity to step back and reassess the approach.

This is not about weakening standards. Rather, it is about being proportionate and coherent, organizing stress testing in a way that adds meaningfully to both supervision and risk management.

Stress testing can be a force for good, but only if it is more about risk management than template filling and process. It is critical that we start the process of improving the coordination and harmonization of supervisory stress testing, so that we can work toward embedding this powerful tool for the good of the financial system.

Jo Paisley is the Co-President of the GARP Risk Institute. Paisley worked as the Global Head of Stress Testing at HSBC from 2015-17, and has served as a stress testing advisor at two other UK banks. As the Director of the Supervisory Risk Specialists Division at the Prudential Regulation Authority, she was also intimately involved in the design and execution of the UK's first concurrent stress test in 2014.