Like many multinationals, packaged-foods giant General Mills relies heavily on sustainable freshwater supplies. It needs neither too much nor too little, and of sufficient quality - a Goldilocks scenario that rarely happens. Indeed, many of the company's plants are in places like China, India and California, where water stress is endemic.

As a result, management devotes a lot of effort to measuring and managing water risks - attempting to anticipate and influence things for the best, while planning and preparing for the worst.

Company officials regularly review specialized water-risk filters, such as those of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and World Business Council for Sustainable Development, and maps of water-stressed areas published by non-governmental organizations (NGOs). They seek out academics and consultants for insights on local precipitation levels, flood potentials and irrigation intensities, and then prioritize the most at-risk geographies for action - all as part of their enterprise-level risk mitigation.

Water risk management is a global issue that, by its nature, is also intensely local, says Jeff Hanratty, General Mills' applied sustainability manager. At industrial scale, there is no global marketplace to turn to. You get what the watershed gives, no more, no less.

“It's not like climate change, where it's the same impact if you emit carbon in Cincinnati or China,” Hanratty says. “Water risks are very geographically specific. You have to work with what the watershed provides.”

Global Dimension

Fueled by climate change, population growth and manufacturing and agricultural production, water quality and quantity are under increasing pressure around the globe.

A color-coded interactive map, published by the World Resources Institute's Aqueduct initiative, shows almost all of India, large chunks of Africa and northern China, and parts of the American southwest bathed in the brown that designates “extremely high” water stress. Those local populations use more than 80% of available surface and groundwater annually.

Things are no better on the water-quality front. According to UN estimates, 80% of wastewater is released into the environment without adequate treatment. Many corporate operations require clean, or even “ultra-pure,” water, and pumping dirty stuff into already-fragile watersheds only exacerbates the challenges, while alienating the neighbors.

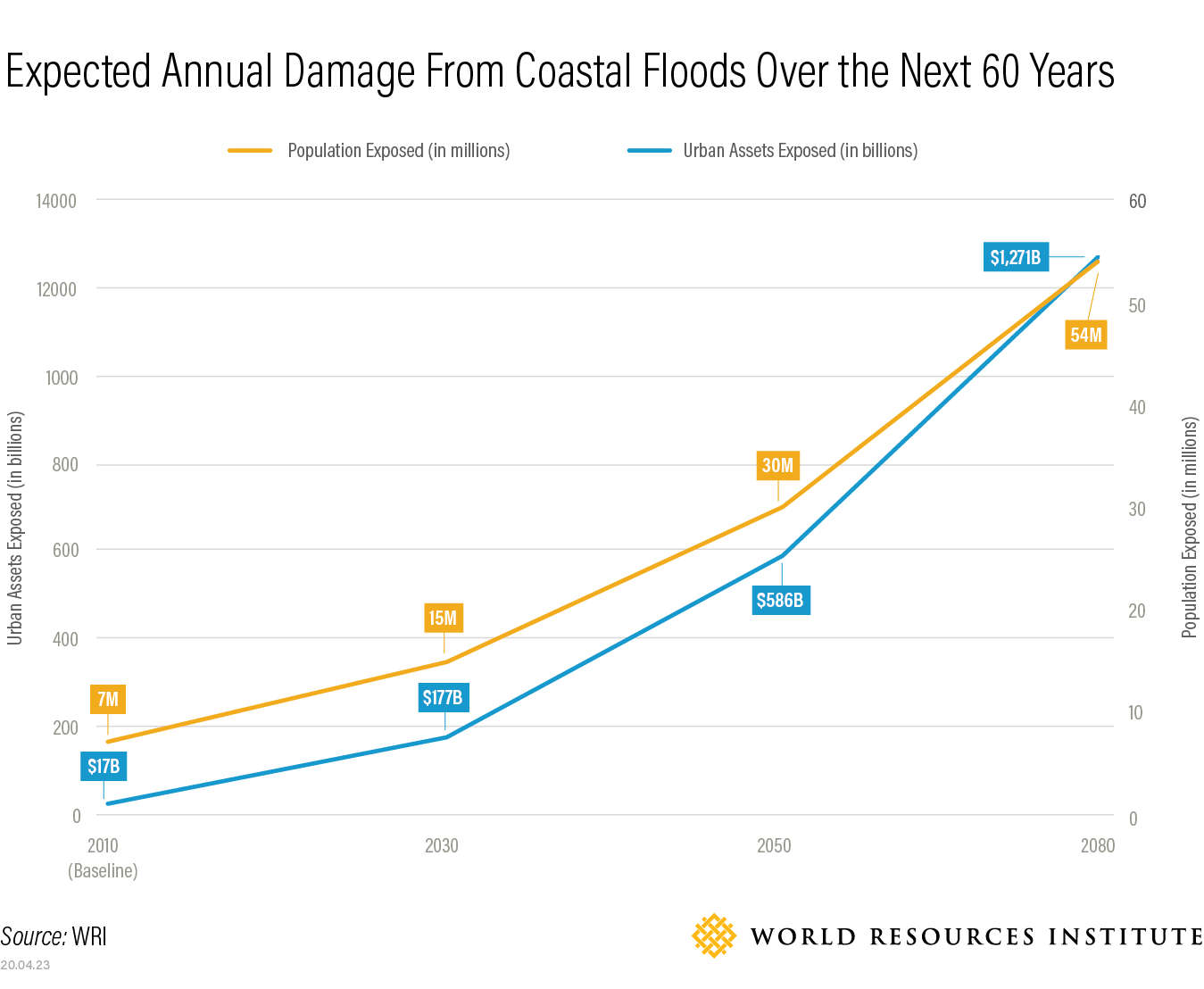

At the same time, floods and droughts are getting more severe, attributed by many to climate change. In March 2019 alone, insurers reported more than $8 billion in global losses due to flooding.

This is the world that companies must operate in, and it's getting more costly. CDP (Carbon Disclosure Project) estimates that companies lost $38.5 billion in 2018 from water-related shutdowns, slowdowns and other operating issues.

The World Economic Forum's Global Risks Report 2020, published in January, ranked water crises eighth among the risks most likely to cause economic harm during the next decade (extreme weather was first), and fifth in terms of potential impact (climate action failure was first). Of the “global shapers” responding to the WEF Global Risks Perception Survey, 86% expected water crisis-related risks to increase in 2020.

Freshwater is vital to all kinds of corporate manufacturing, supply-chain and logistical processes, and it's used in myriad ways - to clean and transport products, heat and cool plants, feed animals and raise crops.

As for quantities: It takes nearly 20,000 gallons of water to manufacture a car, 3,000 gallons to make a smart phone, and 1,800 gallons to yield one pound of beef. A wafer fabrication plant can use up to 150 million gallons per month to produce 40,000 30-centimeter silicon wafers for semiconductors, according to China Water Risk, a Hong Kong-based nonprofit.

“No industry can survive and thrive without a clean, sustainable supply of water,” says Kirsten James, water program director for the sustainability-investment nonprofit Ceres.

Financial and Capital-Market Implications

The risks of water dependence are drawing scrutiny from ESG (environmental, social and governance) investors and ratings services. Last September, for example, Moody's Investors Service warned that the mining industry faces higher risks of facility shutdowns due to water-availability and pollution concerns - factors that could affect a company's ability to fund future growth.

“Water risks are often about top-line revenues and access to the capital markets,” says Monika Freyman, a director of investor engagement for Ceres.

“If you don't manage the risks effectively,” she adds, “you're not able to expand or move into a market as rapidly as you want to because of water shortages. You can't expand production because the community is concerned about local water impacts. Proactively managing water risks is a license to grow.”

In the worst case, water-related risks can snowball, with quantity and quality concerns resulting in community pushback and regulatory consequences. In some cases, public outcry can lead to reputational damage and force a company to close operations.

It happened to Coca-Cola: Groundwater shortages and pollution concerns in the early 2000s near a bottling plant in Plachimada, India sparked protests and led to the facility's closing.

Similarly, Newmont Goldcorp was forced to halt gold and copper mining operations at its Conga project in Peru in 2011.

Water risks can also touch corporate supply and logistics chains in ways that can dent profitability and threaten growth. Olam International, a global commodity trader, saw profits in the second quarter of 2018 decline 36% due, in part, to a drought in Argentina that hurt peanut suppliers.

In 2018 and 2019, low water levels on the Rhine River slowed shipping to a trickle, causing shipping bottlenecks and plant shutdowns for chemical companies in central Europe.

“There was no water to ship their goods, so they had to shut down production,” explains Peter Adriaens, CEO and co-founder of Equarius Risk Analytics, a Michigan-based fintech start-up. “That's a real water risk with a significant bottom-line impact.”

Managing the Risk

The mounting risks and scrutiny are prompting companies in industries as diverse as mining, energy, semiconductors and apparel to get more serious about calculating and categorizing various types of water risks.

In a 2019 Ceres study of 35 large publicly traded food companies, for example, 77% cited water as a risk factor in their financial filings, up from 59% in 2017. About a third of those firms charged boards and senior management with water-risk oversight and strategy, up from 10% two years earlier.

In a survey by GreenBiz, a business sustainability publication, and Ecolab, a water solutions company, 88% of large firms in a broad cross-section of corporations reported setting some internal water-related targets to aid in their risk management efforts.

But the field is new enough that best practices are still in development. No one has a crystal ball to predict precipitation amounts with certainty, while local water-management practices vary wildly, often marked by politics and underinvestment.

“It's very tricky and complex to manage,” says Stuart Orr, freshwater practice leader for the WWF. “No company ticks a box and says, 'OK, we've done water,' like they do with other environmental assessments. It's too complicated.”

Categorizing the Risk

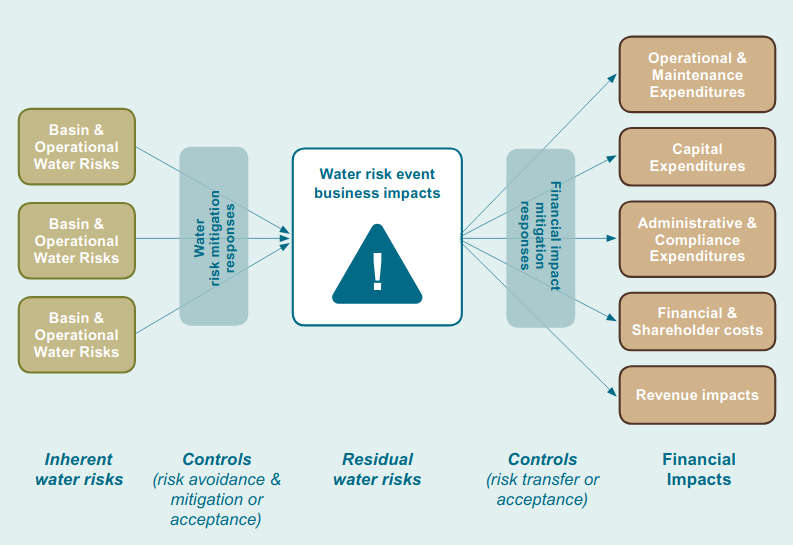

Corporate water risks are often divided into three broad categories: physical (quantity and quality), regulatory (the potential for local authorities to limit usage or influence the pricing, for example) and reputational.

It ultimately comes down to quality and quantity. If there is enough water in a watershed, then there likely won't be much risk. If not, business-continuity, profits and access to capital markets can be jeopardized.

While risks must be weighed watershed-by-watershed, governance often falls within a company's enterprise risk management framework.

At General Mills, water risk is studied intently, but as a triggering event for bigger-picture disruptions like commodity pricing volatility and business interruption. It is not a standalone endeavor.

“If a plant gets shut down, it could be caused by water, political instability or trade [conflicts]. They all create the same risk,” Hanratty says. “We've assessed the impact of that end result in advance.”

A clear policy tone is set at the top of the organization. General Mills' board receives several reports each year with data on local watersheds, as well as political and social issues, to help prioritize investments by the value they will bring.

Done proactively, such exercises can influence plant-siting decisions, facility acquisitions, supplier choices, technology investments, even product-development and marketing strategies.

Art and Science

Water risk management is part art, part science - a hard-number exercise that often starts by overlaying publicly available water-stress maps on the corporate's operations, and then digging deeper on facilities that appear to present the greatest risks and uncertainties.

Among the popular tools are the World Resources Institute's Aqueduct and WWF's Water Risk Filter. Ecolab's Water Risk Monetizer helps quantify the risks in financial terms.

Those are good starting points; a growing number of companies hire outside specialists to complement in-house sustainability and risk teams.

Nick Martin, a senior consultant with Antea Group, which helps companies assess water risks, likes to perform “source vulnerability assessments” to determine the health of specific watersheds for big-picture planning purposes, as well as local plant managements' understanding and buy-in on water-related issues.

“Could water result in shutting down a facility or disrupting our supply chain?” he asks. “If you wanted to double production, could you get double the water we use today?”

Much of the work can be done remotely and by accessing reports from local regulators and utilities, though the figures can be unreliable or tainted by political bias. For facilities at the highest risk, Martin does site visits to get a feel for plant management's understanding of the issue and the local dynamics.

“We look at the hydrology of the area,” he says. “What is the structure of the aquifer? What's the condition of the lakes and rivers? How much demand is there versus precipitation levels? What are the demographics of other users? What's the regulatory environment?”

To assess reputational exposure, Will Sarni, CEO of the Water Foundry, a consulting firm, often performs “sentiment analyses” to gauge local perceptions of the company's operations. “From there we assign a dollar value to it: If this plant shuts down for one week, it will cost this much. If the brand takes a hit, it will cost that much,” Sarni explains.

Value vs. Price

Pricing is another key challenge. For a variety of political and historical reasons, the bill a company gets from the local utility (or for extracting water itself) never comes close to reflecting the commodity's true value to the operations.

Underpriced water makes it difficult for companies to identify and quantify the risks, because they aren't easily recognized on a balance sheet or income statement.

WWF's Orr says that he was assured by one company's executive that its risk in one water-stressed location was low because the water was cheap. “I said, 'Boy, you really don't understand this . . . When your asset runs out of water, is that an issue? Well, guess what? That's about value. Price isn't going to tell you that.'”

To make smarter decisions, a risk-adjusted “internal price” for water is calculated to reflect its true value and cost by location.

This can take different forms. In a facility where water's primary purpose is heating or cooling, for example, understanding the energy and other costs associated with those activities can lead to investments - say, systems that reuse warm water instead of discharging it and heating a new batch - that generate significant savings.

When Microsoft built a new data center near San Antonio, Texas, water risk was a big concern. The local watershed is already stressed, and data centers use a lot of water for cooling.

“We recognize that we're consuming water in water-stressed areas, and we want to minimize our impact,” says Paul Fleming, Microsoft's water program manager.

Using Ecolab's risk monetizer, Microsoft analyzed water stress in the area, groundwater recharge levels, energy costs, other corporate water users, “social impacts” like biodiversity, and other externalities to derive a risk-adjusted internal price that is 11 times greater than what it actually pays for water.

Microsoft concluded that it would save $140,000 annually by investing in technology that uses recycled “graywater,” rather than freshwater, for cooling.

Context-Based Targets

While such risk-adjusted numbers don't actually show on a financial statement (they're more like “shadow prices,” Fleming says), they provide a construct for risk managers to compare and contrast facilities and prioritize investments and other actions.

“If a business can monetize the risk, it can measure and manage it proactively,” says Emilio Tenuta, Ecolab's vice president of sustainability. “You can't make decisions based simply on current market price.”

Such “context-based water targets” are the latest effort to bring clarity to water risk. In simple terms, a company with 100 plants around the world facing differing levels of water risk might choose to invest only in 10 plants where mitigation efforts carry the biggest financial benefit.

“A global company might have hundreds of facilities and thousands of suppliers, which means you have to prioritize,” Antea's Martin says. “You can't do everything.”

Network Assessments

Internal pricing exercises are increasingly common but not universal. At General Mills, 99% of the water risk comes from outside of its plants, in the local farms that supply grains and other essentials for its products.

“Trying to reduce water impacts in our plants is important, but it's not going to move the needle,” Hanratty says. “We're focused on our watersheds,” studying factors like local farm irrigation intensities and rainfall levels.

It also performs full-out water risk assessments of its entire network every three years to identify areas where ingredients such as oats, cocoa and almonds are vulnerable to water risks. The process has led General Mills to designate eight priority areas - four in the U.S., three in China, and India's Ganges River valley - where it engages with other corporates and local officials to address watershed health.

In California, home to the world's largest almond crop, General Mills has joined with NGOs and other corporates, including Molson Coors Beverage Co. to study how to recharge aquifers without disrupting local farms.

Such activities are vital to risk management for avoiding reputational damage and operational disruptions. “If we lost the almond crop in California, it would seriously impact our Nature Valley [granola] business,” Hanratty notes. “You can't buy all those almonds someplace else.”

Leverage with Suppliers

Apparel maker Levi Strauss & Co. takes a harder line with some of its suppliers. A recent house assessment concluded that a pair of jeans uses 1,000 gallons of water over its entire life cycle - from crops and production to end-user laundering - 68% of which involves growing cotton.

Levi Strauss produces much of its apparel in “high-water-risk areas” like China, Pakistan and Mexico. To make its supply chain more sustainable, it has pressed farmers to become more water-efficient or risk losing its business.

“What we've said to our suppliers is that if you're in a high-risk water location, by 2025 you need to reduce your absolute water use by 50%,” Michael Kobori, Levi's vice president of sustainability, said at the Thomson Reuters Aquanomics conference in September 2019.

In a water-stressed world, anticipating and managing such risks is viewed not only as a sign that a company is thoughtful about its communities and the environment, but also as a point of strategic differentiation, competitive advantage, even a social license to operate.

Adriaens of Equarius predicts that the scrutiny will only increase. “These are still early days,” he says. “I'm convinced that it won't be long before water is priced into a company's share price.”