From consulting firms and think tanks to central banks and the International Monetary Fund, there is no shortage of documentation and data points on the perils of the world and, as categorized in the World Economic Forum’s annual global risks reports, their economic, environmental, geopolitical, societal and technological consequences. It’s a given that these factors interact with each other and affect entire populations and businesses, governments and non-governmental organizations on every level.

The full-time and real-time nature of risk monitoring amid accelerating global change, market uncertainty and complexity may call into question the lasting value of any published assessment. However, risk rankings and dashboards are increasingly dynamic, the WEF’s and others’ output is less static and one-off than in the past, and there are attempts to look beyond what is near-term and in the foreground.

This is not to minimize the magnitude of current and ongoing crises and the upheavals they cause.

Indicating the persistence of cyber threats, they ranked No. 1 in Depository Trust & Clearing Corp.’s Systemic Risk Barometer late last year and the Allianz Risk Barometer in January. In the latter survey, business interruption was a close second. “For most companies, the biggest fear is not being able to produce their products or deliver their services,” said Joachim Mueller, CEO of Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty.

Benchmarks earlier this year like those of the WEF, Eurasia Group and Control Risks came down squarely on such concerns as pandemic or endemic coronavirus, cybersecurity, and the Ukraine crisis which, by February, began to overshadow much else, McKinsey & Co. pointed out.

Rod Schoonover: “Accelerated reconfiguring” of the world order.

And there are inevitably interconnections and spillovers. Rod Schoonover, head of the Ecological Security Program at the Council on Strategic Risks, sees “a climate component to the results or the effects of the invasion” because of Ukraine’s sizable agricultural production and potential costs to countries dependent on it. “I think we’re looking at an accelerated reconfiguring of the international world order and what its effects are on energy and food, finance,” he said in a Marsh McLennan Q&A. “Climate change can no longer be thought of as some externality that doesn’t affect geopolitics and security.”

Yet the Russian offensive is not all there is in geopolitics: The Council on Foreign Relations considers Ukraine one of six conflict areas of critical impact on U.S. interests, the others being Afghanistan, East China Sea, South China Sea, Iran and North Korea. Eleven others are deemed to be of significant impact.

Writing in Canada’s CIGIonline, Michael Den Tandt warns that preoccupation with the latest “mortal threat” can cause leaders to “fail to address other problems that can lead to even more acute outcomes. No one who paid attention to the aftermath of the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, also a war of choice, can fail to see the cascade of consequences leading from then to now . . . Among the cluster of risks, three stand out: climate, trade and the digital commons."

An essay by the research team at analytics firm Northfield Information Services lists several key economic and geopolitical takeaways for investors: risk of stagflation, limiting central bank tools; global supply chain problems exacerbated; longer-term macroeconomic impact of increased military expenditures; geopolitical volatility driving market volatility; and indirect effects, such as bolstering China’s efforts to reduce the dollar’s preeminence as a reserve currency.

Pessimistic Perceptions

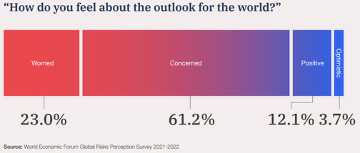

Cataloguing as many as three dozen separate risks, the World Economic Forum report each year charts interconnections between risks and seeks to rally public- and private-sector leaders to collaborate to keep them in check. “Economic, geopolitical, public health and societal fractures – which increase after pandemics – risk leading to divergent and delayed approaches to critical challenges facing people and planet,” says the WEF’s latest, the 17th in the series. Responses to the forum’s Global Risks Perception Survey were largely pessimistic: Regarding the outlook for the world over the next three years, 79.2% came down on the side of “negative scenarios”; 84.2% were either worried or concerned.

Connecting the invasion of Ukraine to the economy at large, IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva said in a March 10 media briefing that the human toll, inflation, sanctions and related spillovers were likely to tamp down the global growth forecast coming in April. In January, the World Bank said global GDP would rise 4.1% in 2022, down from 5.5%.

As McKinsey’s February executive intelligence summary tallied recent events, in addition to imposition of sanctions: Germany “suspended the approval process for the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia. Russia is the European Union’s main supplier of natural gas, crude oil, and solid fossil fuels – types of fuel that produced most EU energy in 2019. Another area of concern is wheat and other grains; nearly one-quarter of the world’s wheat supply is produced in Russia or Ukraine. No U.S.-EU sanctions apply to Russian grain exports as of today. Russia has amassed large gold and currency reserves, much of it yuan-denominated. Russia signed agreements in February to supply China with more grain and natural gas.”

Reports from the regulatory sector – such as the U.S. Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), the Federal Reserve Board and the Bank of England – annually or more frequently examine economic and market factors that may pose threats to financial stability or require vigilance. The Fed’s November report included analyses on market volatility due to changes in retail equity trading, the role of foreign investors in the March 2020 U.S. Treasuries turmoil, central counterparty liquidity, cyber risk, and the Fed’s own “work to identify and address climate-related financial risks.”

The importance of analysis and information sharing among the constituent agencies of the FSOC came across in a comment amid market uncertainty in early March by Securities and Exchange Commission Chair Gary Gensler. “We're staying close with the rest of the FSOC agencies” as well as banking and securities regulators “across the globe,” he told Yahoo Finance. Within the “multiples of tens of trillions of dollars of assets under management here in the U.S., only a fraction of 1% are invested in Russian securities or ADRs [American depositary receipts]. We’re going to stay alert for any cyber risks or any other market-functioning risks. At least for these handful of days so far, the market functions have been operating relatively well. But what comes tomorrow? What comes in the future?”

The soberly presented products of deliberative research may have been rhetorically upstaged by United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres’ declaration in January that countries “must go into emergency mode” because “we face a five-alarm global fire” from the combination of the COVID-19 and climate crises, lawlessness in cyberspace, diminished peace and security, and a “global financial system [that] is morally bankrupt. It favors the rich and punishes the poor.”

Secretary-General Guterres: “A five-alarm global fire.”

Guterres is hardly alone in decrying wealth and social inequalities and how they have been exacerbated by the pandemic and other shocks, but he was particularly harsh in judging that “the divergence between developed and developing countries is becoming systemic – a recipe for instability, crisis and forced migration. These imbalances are not a bug, but a feature of the global financial system.”

“A Core Function of Business”

While Guterres’ criticism may be reminiscent of recriminations aimed at the financial sector in the crisis of 2008-’09, the 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer offers some counterpoint. As “a vicious cycle of distrust” envelops government and media, the advisory firm’s 28-country survey found, business is more trusted by wide margins. More than eight out of 10 say CEOs should take leadership on policy matters, and 64% of investors look to back businesses aligned with their values.

“Business must now be the stabilizing force delivering tangible action and results on society’s most critical issues” such as climate, inequality and racial justice, said CEO Richard Edelman. “Societal leadership is now a core function of business.”

At the same time, 52% of survey respondents say capitalism does more harm than good in its current form. Edelman Trust Index scores fell in developed democracies including Australia, France, Germany, U.K. and U.S. The scores are higher in China (83, versus 43 in the U.S.) and the UAE (76). Edelman said this is because “respondents in every developed country studied believe they will be worse off financially in five years, and 85% fear they will lose their jobs to forces including automation.”

Among nine industry sectors in the study, financial services ranks last, though the proportion trusting it has risen to 54%, from 52% in 2021 and 44% in 2012. (Financial services is the only sector to score under 50% during the 11-year span, and its current grade is the only one considered “neutral,” because it is below the 60% trust threshold.) The top trust scorers this year are technology (73%) and healthcare (69%).

The rapid and decisive corporate withdrawals from Russia may represent a new activism template, according to John E. Katsos and Jason Miklian in Marsh McLennan Brink: “Firms that moved quickly have earned reputational rewards for leaving . . . What’s interesting is how aggressive some shareholders have been in expressing their displeasure . . . We might see shareholders, especially the biggest ones, being much more aggressive in their statements about what they expect from companies.”

Medium and Longer Terms

The Federal Reserve, in the November 2021 Financial Stability Report, cited an ongoing process of market outreach for insight on Near-Term Risks to the Financial System. The exercise “considers possible interactions of existing vulnerabilities with three broad categories of risk”: a significant slowdown in the pace of economic recovery; a sudden increase in interest rates; and risks emanating from China, other emerging market economies and Europe. The most-cited shocks anticipated over 18 months were: persistent inflation/monetary tightening; vaccine-resistant variants; China regulatory/property risks; U.S.-China tensions; cryptocurrencies/stablecoins; climate/weather; and risk-asset valuations/correction.

In the 10th annual international survey of board and C-level perspectives on risk, conducted by consulting firm Protiviti and the Enterprise Risk Management Initiative of North Carolina State University’s Poole College of Management, pandemic-related and talent issues – particularly in view of the Great Resignation – were top of mind.

“The tectonic plates of traditional workforce models and talent retention have shifted dramatically as a result of the global pandemic and digital transformation, a dynamic which isn’t expected to go away any time soon, according to global leaders,” said Jim DeLoach, Protiviti managing director and report co-author with N.C. State professor Mark Beasley. “Looking forward, businesses need to shift their focus to adapting to the ‘new nimble’ rather than searching for a ‘new normal.’”

Protiviti and N.C. State probe anticipated changes over 10 years. Among 36 macroeconomic, strategic and operational risks in the survey, digital disruptions and required upskilling and reskilling jumps from No. 4 to No. 1 in 2031.

“In reviewing year-over-year risk levels in all six industry groups we examined, looking out 12 months and over the next decade, our respondents are apparently more comfortable with the risk landscape near term as the pandemic transitions to an endemic state,” according to Protiviti executive vice president Pat Scott. “But they are casting a wary eye toward the prospect of increasingly complex and competitive markets as the disruptive 2020s unfold.”

“Concerns about digital disruption have ranked at or near the top of our survey for the past several years, even in 2021 when the responses were otherwise dominated by COVID,” said the report’s commentary on the financial sector. “At the onset of the pandemic, we predicted that legacy modernization efforts might slow or be paused as organizations responded to immediate operational and health-and-safety challenges, but that medium to long term, COVID would actually accelerate the transition to a digital world. This has played out even more quickly and definitively than we expected.”

Climate to the Top

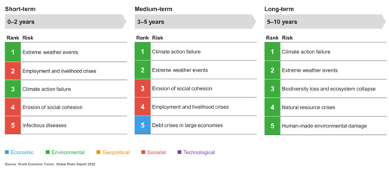

In its attempt to capture changing expected-risk perceptions over time, the World Economic Forum found infectious diseases is in the top five only in the zero- to two-year timeframe. In the medium term of three to five years, the environmental risks of climate action failure and extreme weather are first and second, followed by erosion of social cohesion, which is one place higher than on the short-term list.

Five to 10 years out, all of the top five risks are environmental, again led by climate action failure. Nos. 6 through 10 are erosion of social cohesion, involuntary migration, adverse technology advances, geoeconomic confrontations, and geopolitical resource contestation.

On a farther frontier, the WEF devotes a chapter to “Crowding and Competition in Space.” The contexts are geopolitical/military and public- and private-investment, along with “a higher risk of collision between near-Earth infrastructure and space objects, which could affect the orbits upon which key systems on Earth rely, damage valuable space equipment, or spark international tensions in a realm with few governance structures.”

There is the business risk that “if manufacturing, tourism or other space ventures fail to take flight, speculators and space industry companies could see their bubble burst. Similarly, grassroots campaigns to ban space pollution and prevent privatization of important science data could give investors pause, stifling the unmitigated venture financing in the field.”

Being Prepared

Risk management service providers share a sense of ongoing urgency and building on lessons from the recent past.

Market volatility during the pandemic period and readiness for coming catastrophic or novel occurrences indicated a need to reassess hedging programs and other market risk management approaches designed five to 10 years ago, says Amol Dhargalkar, managing partner and global head of corporates at advisory and technology firm Chatham Financial. Effective integration of technology tools, the need to be proactive and anticipatory, and collaboration are key elements, as forecasting is a “team sport.”

Riskonnect describes its solutions as “integrating data, connecting risks, and correlating their relationships,” and integrated risk management strikes a chord with its growing customer base, says CEO Jim Wetekamp. The “core idea” for dealing with such ongoing concerns as COVID, ESG, cyber, and remote or hybrid working is to “put risk under one roof and drive cross-functional transparency.” All services should be inventoried, and each should have a mitigation plan to overcome disruption, he adds.

Atul Vashistha, chairman and CEO of Supply Wisdom, stresses the value of location monitoring, noting that his risk intelligence firm had signals of a virus outbreak from Wuhan, China, in early January 2020. He strongly advocates continuous risk monitoring and maintains that concentrating on financial and cyber risks, as essential as that is, does not capture the total picture.

DTCC’s Andrew Gray: Black swan events appear more frequent.

“Financial and cyber factors are often lagging indicators of trouble,” Vashistha wrote in GARP Risk Intelligence. “Take, for example, COVID: What started as a location-based risk then cascaded into a people risk and an operations risk, before financial and cyber events occurred. By ignoring location, people, operations, and other risk factors, enterprises were missing critical early warnings that would have enabled more resilient responses.”

Andrew Gray, managing director and group chief risk officer, Depository Trust & Clearing Corp., said at yearend that firms will have to continue prioritizing risk mitigation and resilience because “black swan events seem to occur more frequently than in the past. While the risk landscape will remain highly uncertain due to the emergence of new COVID variants and their impact on economic growth as well as ongoing inflation, supply chain shortages and energy price increases, risk management professionals must remain vigilant and identify opportunities to further enhance efforts to mitigate risk and build greater resilience to protect their firms and the broader financial system from market shocks and disruptions.

“In addition,” Gray continued, “with the frequency of cyber, ransomware and phishing attacks continuing to increase, the industry will need to focus on further strengthening public-private partnerships, participating in war-gaming exercises and making investments in tools and technology as part of their security, recovery and operational resilience strategies.”