The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) recently published an interesting framework for climate risk that includes helpful advice on how a financial institution can integrate climate hazards within its existing risk taxonomy. However, the set-up of the BCBS infrastructure is very traditional (with risk drivers leading to financial risk), so it is questionable whether it properly addresses the unique features of climate risk.

The management of emerging risks, like climate change, typically goes through a number of stages, that we can, for simplicity's sake, summarize in three phases.

First, an emerging risk needs to be acknowledged as a substantial threat. This is what happened with climate change some 50 years ago, with the publication of the Limits to Growth report to the Club of Rome in 1972.

Mainstream financial risk managers, moreover, have acknowledged climate risk as a substantial risk for some 10 years now - and GARP launched its Sustainability and Climate Risk (SCR) certification in January 2020. These developments have fueled the following question: How should climate risk be measured and managed in relation to other risks in the risk taxonomy?

In the second phase, measurement methodologies are developed that capture the risk exposure and its impact. For climate risk, this experimental phase has been taking place for a while.

During this phase, models are developed to support risk management, predict loss outcomes for the near future, and quantify capital. Professionals, both at banks and at other institutions (e.g., universities) also experiment with approaches. Is it, for example, better to apply a hazard approach or beta model to predict occurrences? And do we need a copula model to link climate scenarios to macroeconomic events or are there other, more simple approaches?

Modeling approaches in phase two are not only developed locally, but also top-down, by regulators and standard-setting bodies. They often act first as aggregators, collecting the range of practices, and subsequently publish reports in which they discuss the breadth of risk approaches and identify best practices.

In the third phase, with a focus on canonization and codification, the regulators go a step further: a best practice is selected and codified in a minimum standard. For example, during this phase, the value-at-risk (VaR) approaches that were developed by U.S. investment banks became the prescribed way of calculating regulatory capital.

The BCBS Perspective on Climate Risk

For climate risk, the world is currently at a most interesting moment. While we're still in the experimentation phase, a glimpse of the third phase can be seen now and then.

As we develop models for climate risk and experimenting, the following fundamental questions rise to the surface: (1) Should climate risk be a new risk type to add to the risk taxonomy, next to credit, market and operational risk, or is it part of one or multiple existing risk types? (2) What are the main components of climate risk and what main drivers have to be distinguished? (3) How can we account for complex factors, like the flood risk connected to real estate exposures in coastal areas, which might increase the PD of the obligors linked to these exposures?

In “Climate-related risk drivers and their transmission channels,” the BCBS develops a framework for the modeling and management of climate risk. Referring to the physical and transition drivers of climate change, the authors of this BCBS report provided a clear answer to our first question.

“Evidence suggests that the impacts of these risk drivers on banks can be observed through traditional risk categories,” they write. “Traditional risk categories used by financial institutions and reflected in the Basel Framework can be used to capture climate-related financial risks.”

In short, the BCBS believes that climate risk can be observed, measured and managed through the current taxonomy - which comprises credit, market, operational, liquidity and reputational risks. So, according to the regulator, there is no need to make any drastic changes firms' existing risk taxonomies.

While the traditional risk taxonomy can remain intact, the BCBS advises firms to take the following climate risk layers into account:

- Climate risk drivers. These comprise physical drivers and transition drivers. Physical drivers are either acute (wildfires, heat waves, floods) or chronic (droughts, sea level rises). Examples of transition risk drivers are government policies and technological change, which may not only lead to stranded assets at banks' clients but also have the potential to destroy these assets' income-producing capacity (for interest and debt service) and collateral values.

- Transmission channels. Climate risk drivers lead to financial risks. According to the BCBS, there are two transmission channels: microeconomic and macroeconomic. Through microeconomic transmission channels, the climate risk drivers affect individual households, firms and sovereigns; macroeconomic channels, on the other hand, impact the overall economy.

- Financial risks. Through the transmission channels, the climate risk drivers add to the risk exposures in the traditional risk taxonomy - e.g., credit, market and operational risks, as well as reputational risk and liquidity risk.

This straightforward framework is enhanced by acknowledging modifiers in the second layer - i.e., the transmission from climate risk drivers to financial risks is intensified, or reduced, under the following circumstances:

- Geographical heterogeneity. A financial institution will face less flood risk if, for example, its assets are not in the vicinity of seas or rivers.

- Amplifiers. Risk-driver interaction can increase the impact of the climate risk drivers on the financial risks - e.g., a rising sea level (a chronic physical risk) can interact with flood risk (an acute physical risk).

- Mitigants. Insurance against climate-related risks is one example.

One of the conclusions of the BCBS paper is that this climate risk is particularly connected to credit risk. Indeed, this is the risk type that is most affected by climate risk drivers, according to the BCBS.

One of the examples that is discussed in the paper is the way households can be impacted by acute or chronic physical risks. As a result of severe weather events and/or chronic flooding, for example, residential real estate values will be impacted. (See, for instance, the 2018 paper by Ortega and Taspinar, which concludes that prices for flooded neighborhoods in New York City dropped 20% after Hurricane Sandy, followed only by a partial recovery.)

These risks translate into both lower collateral values (loss-given default) and a decreased capacity for owners to repay mortgage debt (probability of default).

The Uniqueness of Climate Risk: Irreversible Impact

The BCBS framework is very helpful for application within the banking sector. But there are also some caveats. The model is very traditional in that risk drivers (say, a storm) lead to changes of intermediate variables (financial health of an obligor) and to financial risk (higher PD and/or LGD).

Although the framework recognizes amplifiers, non-linearities and tipping points, it is still traditional in its entire layout. The question is whether this is good enough.

What makes climate risk unique is that the underlying causes lead to irreparable damage and accelerating dynamics. We're currently dealing with structural changes, for example, that may impact our way of living on this planet for generations to come.

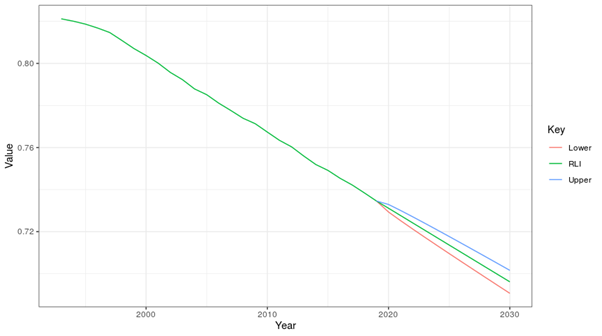

A case in point is the biodiversity Index of Species Survival, based on the Red List Index (RLI). This is one of the indices of the sustainable development goals of the United Nations, and demonstrates the accelerating loss of biodiversity that leads to irreversible changes to Earth's ecosystem.

Figure 1: Index of Species Survival (UN SDG Goal 15)

The RLI index tracks data on more than 20K species of mammals, birds, amphibians, corals and cycads. The development of this index (and similar studies) shows that biodiversity is declining faster than at any other time in human history, leading to unchartered territory in terms of food production and the ecosystem.

Parting Thoughts: More Work to be Done

In response to these alarming trends, action from all players in society is required to safeguard critically-endangered species. However, in the current BCBS framework, irreparable damage and irreversible change do not seem to be satisfactorily considered.

These worrying issues can be addressed through the development of proper climate risk scenarios. Responses need to be drastic, but financial institutions can play an active role in counterbalancing the deteriorating dynamics - instead of just passively applying the BCBS framework.

Dr. Marco Folpmers (FRM) is a partner for Financial Risk Management at Deloitte Netherlands and a professor of financial risk management at Tilburg University/TIAS.