The failure of Silicon Valley Bank and fears of other falling dominoes sparked a firestorm of recriminations and investigations. The regulators whose rapid crisis response may have staved off the dreaded systemic contagion ironically found themselves front-and-center in the blame game while also being in a prime position to identify who and what went wrong, when, why and how.

Their conclusions from official inquiries, and other studies and postmortems initiated in Congress and the private sector, will emerge in the coming weeks and months. But in the light of a new breed of bank run, accelerated by instantaneously viral tweets and the ease of online account access and accompanied by no small measure of pontificating, who has time for patience?

Three weeks after the closings of Santa Clara, California-based SVB on March 10 and Signature Bank in New York on March 12, pithy excerpts from JPMorgan Chase & Co. Chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon’s annual shareholder letter stood out as a summation: “Most of the risks were hiding in plain sight” of the marketplace and regulators, and “this wasn’t the finest hour for many players,” not least bank management.

With the qualification that “recent events are nothing like what occurred during the 2008 global financial crisis,” Dimon contended, “As I write this letter, the current crisis is not yet over, and even when it is behind us, there will be repercussions from it for years to come.”

Soon after, in an April 6 CNN interview, Dimon expressed confidence that “if there are [more bank failures], honestly, they’ll be resolved. I think we’re getting near the end of this particular crisis.”

Still, a final declaration of case – or crisis – closed is some time off. The narratives will be multidimensional, ranging from macroprudential oversight to micromanagement decision-making, gaps in risk management and flaws in corporate culture. Expect increasing scrutiny of how storm clouds and red flags “in plain sight” were either ignored or inadequately addressed in interactions between the failed banks and their Federal Reserve and state banking department supervisors.

Defining a Crisis

Managerial shortcomings and regulators’ performance were catching flak well before Dimon’s characterizations. At a March 22 press conference on monetary policy, Fed Chair Jerome Powell distanced SVB from the overall condition of the banking industry, calling it an “outlier” whose “management failed badly. They grew the bank very quickly. They exposed the bank to significant liquidity risk and interest rate risk” and “experienced an unprecedentedly rapid and massive bank run" by a “very large group of connected depositors.”

A week later, under the harsh spotlight of Senate and House committee hearings, Fed Vice Chair for Supervision Michael Barr contributed “textbook case of mismanagement” to the litany of soundbites. He revealed that supervisory ratings of SVB in summer 2022 resulted in an evaluation of “not well managed,” and concerns were raised about interest rate risk in the fall.

“SVB failed because the bank’s management did not effectively manage its interest rate and liquidity risk, and the bank then suffered a devastating and unexpected run by its uninsured depositors in a period of less than 24 hours,” Barr testified. “SVB’s failure demands a thorough review of what happened, including the Federal Reserve’s oversight of the bank. I am committed to ensuring that the Federal Reserve fully accounts for any supervisory or regulatory failings, and that we fully address what went wrong.”

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen: Guarding against contagion.

Even as they offered the first high-level drill-downs from a regulatory standpoint, Barr and his co-panelists – Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Chairman Martin Gruenberg and Under Secretary of the Treasury for Domestic Finance Nellie Liang – declined to label the recent developments as a crisis.

At the same time, even problems confined to a handful of banks with concentrated technology market exposures were deemed systemic enough to justify augmenting the standard $250,000-per-account insurance coverage. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, who has repeatedly vowed to prevent runaway contagion, intimated in a March 30 address to the National Association for Business Economics that the shocks and lessons of 2008 continue to reverberate.

“When there are cracks in confidence in the banking system, the government must act immediately,” Yellen explained. “This includes making forceful interventions – like we did. As I have said, we have used important tools to act quickly to prevent contagion. And they are tools we could use again . . . It's also important that we reexamine whether our current supervisory and regulatory regimes are adequate for the risks that banks face today. We must act to address these risks if necessary. Regulation imposes costs on firms, just like fire codes do for property owners. But the costs of proper regulation pale in comparison to the tragic costs of financial crises.”

The International Monetary Fund’s Global Financial Stability Report on April 11 sent a message that financial counsellor Tobias Adrian highlighted in an IMF Blog: “Gaps in surveillance, supervision and regulation should be addressed at once. Resolution regimes and deposit insurance programs should be strengthened in many countries. In acute crisis management situations, central banks may need to expand funding support to both bank and nonbank institutions.”

Second-Guesses

If a bigger catastrophe was averted, then coordinated actions by the Treasury, Fed, FDIC, and even a multibank initiative led by JPMorgan to shore up deposits of the teetering First Republic Bank may share credit.

The “forceful intervention” nonetheless took some heat from FDIC alumni. Sheila Bair, FDIC chair during the 2008 crisis and founding chair of the Systemic Risk Council, viewed the blanket SVB and Signature deposit guarantees as an “overreaction” and applied the loaded term “bailout.” Bair considered SVB’s $209 billion in assets to be “not insignificant, but in a $23 trillion banking industry, not something I would consider systemic at all.”

The 16th-biggest U.S. bank in assets, Silicon Valley was not by normal measures systemically important or too big to fail. In stark, concurrent contrast, $574 billion-in assets Credit Suisse had the systemically-important tag. Long-festering financial and governance issues led Swiss regulators to arrange its takeover by the $1.1 trillion UBS.

William Isaac, who headed the FDIC under Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan and is chairman of Secura/Isaac Group, was not alone in warning of the “moral hazard” arising from extraordinary U.S. government protection. Isaac stresses the importance of market discipline, and the SVB-tech industry experience may usher in a new wave of depositor due diligence.

“Startups and their boards need to renew their focus on risk management,” venture capitalist Jonathan Medved, founder and CEO of OurCrowd, said in a LinkedIn post. “Startups and venture investors alike paid hardly any attention to the risks to their financial deposits.” Now they “must run their bank deposits with the same vigilance as they run their own businesses, managing the risk and being clear-eyed about the implications.”

Tools Not Used

“The FDIC should have turned to its 1982 innovation: the modified deposit payoff,” Isaac wrote in the Wall Street Journal. That would give depositors of a closed bank receivership certificates for 80% of their uninsured funds, which could be exchanged for cash at Federal Reserve Banks. They could later collect more than the 80%, depending on the results of FDIC receivership.

William Isaac: Blame the board and management.

While such a “haircut” and the effectiveness of stress testing and other measures may be legitimately debated, Isaac is emphatic that “serious mistakes by SVB's senior management and board of directors are the primary cause of this failure.”

Paul Kupiec, a former associate director of the FDIC Division of Insurance and Research and now an American Enterprise Institute senior fellow, lamented in an opinion article in The Hill that the agency did not invoke the Orderly Liquidation Authority (OLA) for failed banks that was written into the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act.

In another commentary, headlined Bank Regulators Were Asleep at the Wheel, Kupiec asserted that a volatile funding source such as uninsured deposits, highly concentrated bank business or loan categories, “and growth fueled by a new activity” are well-recognized early warning signs within the FDIC. Those “fit both SVB and Signature Bank to a ‘t’,” and questions have arisen about their not getting problem-bank treatment and notices or follow-up from supervisors on matters requiring attention (MRAs) and matters requiring immediate attention (MRIAs).

Connecting Some Dots

FDIC chief Gruenberg, whose agency, like the Fed, aims to have a report out in May, saw “common threads” among SVB, Signature Bank and Silvergate Bank of La Jolla, California, which announced its voluntary liquidation on March 8. The deposits of Silvergate, like Signature an active cryptocurrency payments servicer, were concentrated in a single sector and had fallen drastically since the November bankruptcy of the FTX exchange.

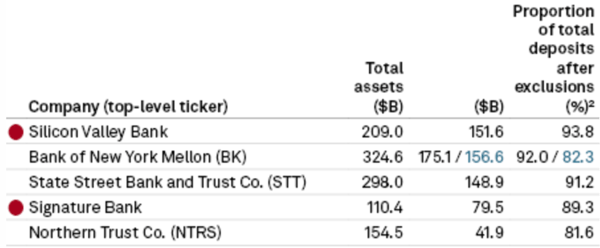

SVB and Signature relied heavily on uninsured deposits, both at around 90% of their 2022 totals, Gruenberg said. That “exacerbated deposit run vulnerabilities and made both banks susceptible to contagion effects from the quickly evolving financial developments,” he added. The associated liquidity risks “are extremely difficult to manage, particularly in today’s environment where money can flow out of institutions with incredible speed in response to news amplified through social media channels.”

Among banks with $50 billion or more in assets, SVB and Signature Bank ranked first and fourth, respectively, in proportion of uninsured deposits as of December 31, 2022. The data from S&P Global Market Intelligence is from call reports. (The blue amounts are from BNY Mellon public filings.) The other three institutions have sizable trust and custody businesses.

SVB and Silvergate Bank had securities portfolio losses in common, with “reaching for yield” leading to “heightened exposure to interest rate risk, which lay dormant as unrealized losses for many banks as rates quickly rose over the last year. When Silvergate and SVB experienced rapidly accelerating liquidity demands, they sold securities at a loss. The now realized losses created both liquidity and capital risk for those firms, resulting in a self-liquidation and failure.

“Finally,” Gruenberg continued, “the failures of SVB and Signature Bank also demonstrate the implications that banks with assets of $100 billion or more can have for financial stability. The prudential regulation of these institutions merits additional attention, particularly with respect to capital, liquidity, and interest rate risk.”

Prior Warnings

Although definitive accounts and assignments of accountability are yet to come, the effects of problematic management strategies and execution could be gleaned from advance statistical indicators as well as post hoc analyses and inferences. Among them:

-- Some underlying issues of the 2023 failures “existed even five years ago,” according to the Congressional Research Service. A 2018 Financial Stability Oversight Council report showed that of SVB’s then $44 billion in deposits, 80% – the highest percentage among medium-size banks – were uninsured. In the five years through March 2023, the deposit total grew by 397%, to $175 billion.

-- The S&P Global Market Intelligence Market Signal Probability of Default (PDMS) model provided early warnings on SVB, Signature Bank and Silvergate. For SVB, the forecasted 1-year PD rose from 1.1% to 2.5% over 10 days last September. It peaked on December 6 at 6%, “which mapped to a ‘b-‘ credit score,” S&P said. That was nearly five times the U.S. Regional Banks sector’s 1.27% median.

-- Andrew Bailey, governor of the Bank of England since March 2020 and previously CEO of the Financial Conduct Authority, reported to Parliament on the March 13 purchase of SVB’s U.K. subsidiary by HSBC: “Over the last 18-24 months,” he stated, “concentration risk, and overlap of clients on the asset and liability side of the balance sheet, had been areas of focus for supervision. The PRA [Prudential Regulation Authority] discussed these with both the firm and the San Francisco Federal Reserve,” SVB’s primary regulator.

-- SVB was in the 99th percentile for highest ratio of uninsured deposits, 90th worst percentile for capital reserves after adjustment for unrealized losses, and 96th percentile for equity risk of major banks tracked by Northfield Information Services. Dan diBartolomeo, president of the risk analytics and advisory firm, opined in a March webinar that months before the bank was closed, billions in borrowings from the Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco were “indicative of internal knowledge of concerns about liquidity.”

Northfield’s Dan diBartolomeo: “A liquidity event, not a solvency event.”

“A bank run is a liquidity event, not a solvency event,” diBartolomeo pointed out, adding that if SVB’s depositors were not closely monitoring that exposure, “shareholders were certainly in a position” to be aware. He also cited an academic “case study” conservatively estimating that some 190 banks with $300 billion in combined assets “are at a potential risk of impairment” to repay insured deposits. Additional “fire sales” caused by uninsured deposit withdrawals could raise that number.

“The probabilistic nature of the unrealized losses being realized in the future belongs in the realm of risk management, not financial accounting,” diBartolomeo asserted.

Don van Deventer, founder of Kamakura Corp. and managing director of Risk Research and Quantitative Solutions at SAS, has been underscoring the importance of stress testing and scenario analysis, and that liquidity and deposit-balance risks needed heightened vigilance in view of rising rates.

“Greed and Stupidity”

A prominent equity portfolio manager, whose name diBartolomeo kept anonymous, told him that “greed and stupidity” were at the heart of SVB management’s failings.

The famed short seller James Chanos had no qualms telling Insider that SVB got caught in a duration mismatch that was not systemic, but rather “affects a few really dumb, greedy institutions” that forsook risk management to chase profits.

“We learned that some bankers are very bad at the basic business of banking,” said Peter Conti-Brown, Class of 1965 Associate Professor of Financial Regulation at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, co-director of the Wharton Initiative on Financial Policy and Regulation, and a Brookings Institution fellow.

Peter Conti-Brown: “Flighty depositors . . . and regulators.”

“We learned that some supervisors, even when they identify these basic risk mismanagements in the system, for reasons that we don’t know, can be extremely slow to implement the reforms needed before it turns to catastrophe,” Conti-Brown said at an April 5 Brookings-hosted event. “And we learned that uninsured depositors are extremely flighty. That might be faster than ever before because of how easy it is on a smartphone to make those withdrawals. We learned that their very flightiness makes regulators flighty too, or at least trigger-happy with declarations of banking crises including the provision of government benefits to those who are not legally entitled to receive them.”

In a Mercatus Center Macro Musings podcast, the UPenn professor said the term “bank panic” applies if SVB “is a victim to macro trends and flighty depositors who didn’t have the right policies in place to back them up.” Another way to look at it is “that the market just beat Silicon Valley out of the business of banking, which the bank gave those depositors every reason to do.”

Also on that podcast, Columbia Law School professor Kathryn Judge observed: “The system should be able to handle banks occasionally failing . . . I think the question that we need to be asking is, why is it we ended up in a situation where these emergency authorities needed to be invoked? And if that possibility was on the table, even as a low-probability matter, why the heck didn’t regulators and supervisors do a heck of a lot more to ward off this happening?”

Identifying with the Culture

To Jon Medved of OurCrowd, Silicon Valley Bank was well ensconced in its high-tech milieu: “Its executives understood the tech sector, offered accounts and products tailored to the needs of the innovation economy, and occupied a special place at the heart of the startup ecosystem.

“But familiarity cannot be allowed to dull our business senses,” Medved went on. “A favorite bar or eatery in Silicon Valley or on Rothschild Boulevard in Tel Aviv might be the perfect hangout. But if it were to suddenly double in size, expand its menu and revamp the decor without raising its prices during a period of high inflation and a supply-chain squeeze, we should query the business model. Regulators and investors appear to have missed the warning signs at SVB.”

To Jeff Laborde, a former Goldman Sachs technology investment banker who is now chief financial officer of procurement technology company JAGGAER, SVB served “a very important purpose. They successfully banked an area of the market that other banks viewed as un-bankable – early startups with no or very limited revenue and no visible prospects for profitability.” After 40 years serving this market, the bank was “comfortable with the risk [and] ostensibly understood it better than others.”

Jeff Laborde of JAGGAER: “Word spread wide and fast.”

“Growth without profitability” became so ingrained, Laborde continued, “that once the economy started to slow down, and interest rates started to pick up, it introduced some structural elements that really exposed the combination of SVB’s tech concentration and the rapid pace of growth in their assets – growth that arguably outgrew them and their ability to manage those assets effectively” in ways they were familiar with.

The run on SVB ultimately was enabled and exacerbated by this tech industry concentration and the tight-knit community of tech players. Once “people started to sense something was wrong, word spread wide and fast among a group accustomed to moving fast.”

Exciting versus Boring

Vanderbilt University law professor and author of The Money Problem Morgan Ricks, interviewed by Ezra Klein of the New York Times, contrasted the “exciting businesses” that were SVB clients with the “boring business model” of a bank for which “loading up on Treasury securities” was historically safe and conservative. Regulators since the global financial crisis were more focused on complex institutions “with lots of derivatives, that are doing securities dealing, that are prime brokers for hedge funds. And Silicon Valley Bank was none of those things.

“It puts a lot of pressure on regulators and supervisors to be very attuned to all types of risks, even some that we haven’t really seen materialize in quite some time. And that’s a tall order.”

ZRG’s Robert Iommazzo: “Reckless behavior” violated trust.

Robert Iommazzo, managing director – Global Enterprise Risk & Analytics Practice leader at talent advisory firm ZRG Partners, sees it as more a story of risk breakdown than of cultures clashing.

“Banking can be summed up in one simple word: trust,” he states. “The market relies on regulators, internal audit and risk executives to help cultivate trust in this sector. In SVB’s case, they were woefully mismanaged for many years – the low interest rate environment coupled with the amount of money many VC and private equity firms plowed into startups made it too good for lending and, in sum, enabled reckless behavior where SVB execs ‘inhaled their own exhaust,’ so to speak.”

Disconnects and Unknowns

It did not escape Iommazzo’s gaze that the SVB board had little in the way of risk management experience, and he believes “equity investors will be focused on this going forward.”

For Clifford Rossi and Sim Segal, risk management veterans and consultants now also in university roles, the latest crisis has re-exposed recurring managerial and behavioral weaknesses.

Rossi, professor-of-the-practice and executive-in-residence at the University of Maryland’s Smith School of Business, perceived a “disconnect” between SVB’s public statements and filings – “they were making it sound like [they] had good practices in place” – and a “much less rosy” reality.

Segal, founder and director of, and senior lecturer in, Columbia University’s Master of Science in ERM program, saw enterprise risk management falling short.

Through media appearances and writings, including in GARP Risk Intelligence, Rossi has been zeroing in on SVB’s board governance – he advocates risk competency certification for directors – as well as its months-long chief risk officer vacancy. The latter, having been documented in public filings, generated considerable media coverage and commentary. (Few other such internal machinations have been disclosed or confirmed. The Washington Post did report, based on anonymous sources, that a risk model was manipulated to tamp down the anticipated impact of rising interest rates.)

According to proxy disclosures, Laura Izurieta, SVB’s CRO since 2016, in early 2022 entered into discussions about transitioning out of that role. She left her position last April and, in the interest of continuity, remained “supporting and advising” around risk, “ongoing initiatives” and the CRO search until October 1. The appointment of new CRO Kim Olson, most recently of Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corp., was announced on January 4.

Olson reportedly followed other top executives out of SVB after the takeover of its FDIC-created bridge bank by First-Citizens Bank & Trust Co. of North Carolina.

For Rossi, this brought to mind Washington Mutual, the only U.S. bank failure bigger than that of SVB. It went through five chief credit officers in two-and-a-half years – Rossi was one of them – “because every one of us was saying the same thing: ‘You’ve got too much risk.’”

He expects that CRO vacancies or turnover, regardless of causes or circumstances, will “raise the antenna of the regulators,” particularly in a case like SVB facing supervisory matters requiring attention.

ERM as Backstop

It is not clear how the CRO void was filled.

“If there was a proper ERM framework in place, then the processes – risk identification, risk quantification, risk-reward decision-making and risk messaging – could have been continuing with another associate stepping in, such as a deputy CRO,” posited Segal, president of SimErgy Consulting.

Villanova Professor Noah Barsky: “A de facto CRO?”

“Basic business practices should have made SVB concerned about their reliance on a single sector,” he maintained. “Well before regulators cautioned SVB, their ERM program appears to have failed to prevent SVB from accepting a risk exposure that should have raised alarm based on routine risk scenario analysis. This could be due to suboptimal ERM processes, although it could be governance issues – not following ERM recommendations.”

Noting that the SVB board’s risk committee – which included former U.S. Treasury official and T. Rowe Price management committee member Mary Miller – met 18 times in 2022 compared with seven in 2021, Villanova University School of Business professor Noah Barsky asked rhetorically in a Forbes article if that “equate[d] to a collective de facto CRO.”

“The board sits at the nexus of banks’ key stakeholders – depositors, investors, regulators, auditors, the capital markets and employees,” Barsky elaborated to Risk Intelligence. “That’s a serious and complicated fiduciary responsibility that seems undervalued in the SVB case.”

“A New-Fashioned Run”

A board-level perspective on the final days of Signature Bank came from none other than Barney Frank, a director since 2015, who as a Democratic congressman from Massachusetts sponsored the Dodd-Frank Act. He later favored the 2018 rollbacks that some critics say left midsize banks too loosely regulated. (“Even applying to SVB the full-strength liquidity rules governing our largest banks wouldn’t have changed its fate,” former Fed Vice Chair for Supervision Randal Quarles argued in the Wall Street Journal. In an April 12 speech, FDIC Vice Chair Travis Hill concurred, as did a Bank Policy Institute finding that “tailoring” was not to blame and that the Fed was not precluded from applying enhanced prudential standards to banks above $100 billion in assets.)

Due to rotate off the Signature board this month, Frank told Barron’s that he learned from Chairman Scott Shay on March 10 that the $118 billion-in-assets bank was “bleeding deposits.”

NYS Financial Services Superintendent Adrienne Harris

In a February 15 meeting with the FDIC and New York State Department of Financial Services (DFS), the agencies gave “no indication of any problems” – though there was some discussion about crypto operations. When Signature was seized March 12, Frank deduced it was “no question, because of our prominent identification with crypto. I can’t think of any other possibility.”

The state’s chief banking regulator, DFS Superintendent Adrienne Harris, didn’t see it that way.

“The idea that taking possession of Signature was about crypto, or that this is Choke Point 2.0, is really ludicrous,” according to CoinDesk’s report of Harris’ remarks at an April 5 conference. Choke Point refers to regulatory efforts to bar certain “undesirables” from banking activities and privileges.

“I just have no other way to say it: What we saw was a new-fashioned bank run,” Harris added. “When you have a high percentage of uninsured deposits, and you don’t have liquidity management protocols in place, you end up in a place where you cannot open on Monday in a safe and sound manner.”

L.A. Winokur is a veteran business reporter based in the San Francisco Bay area.

Jeffrey Kutler is a GARP editor and writer.

Topics: Conduct & Ethics