By measures ranging from revenue and workforce growth to market valuation and mind share, Big Tech stands out in the corporate world. It is also at risk of paying a price for rampant success, if current allegations of anti-competitive or monopolistic practices hit their mark.

Among those taking aim: a U.S. House Judiciary subcommittee, which In a 449-page report last October characterized Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google as “gatekeepers” with “significant and durable market power.” The antitrust panel acknowledged open competition's economic benefits and opportunities but compared the Big Techs to “the kinds of monopolies we last saw in the era of oil barons and railroad tycoons.”

The European Commission in December proposed a Digital Markets Act (DMA) and Digital Services Act (DSA) to keep the gatekeeper platforms within bounds and ensure consumer privacy and other protections.

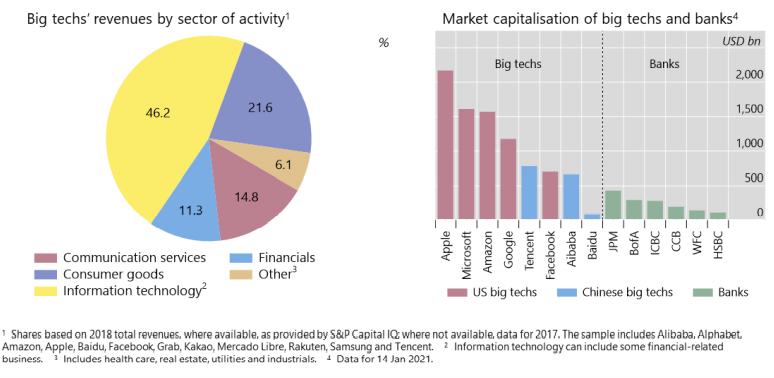

And as these ever-expanding technology giants, whose market capitalizations exceed those of the biggest banks, diversify into banking, payments and other financial services, regulators are facing questions of when and how to supervise them - a line of inquiry that encompasses the fintech innovation trend more generally.

“Big Techs have done something quite remarkable,” AgustÍn Carstens, general manager of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), said in a January talk, Public Policy for Big Techs in Finance. “Within less than two decades, they have gone from being startups to dominating a range of markets. This is unprecedented,” Carstens said, noting that financial services accounted for “only 11%” of Big Tech revenues “so far.”

He went on to say that “overall, it is clear that Big Techs put policymakers in a thorny position.”

It is one that the BIS, which represents the world's central banks and is a highly authoritative voice on governmental policy and regulatory oversight, has begun to work through. In Fintech Regulation: How to Achieve a Level Playing Field, a paper published in early February, Fernando Restoy, chairman of the BIS Financial Stability Institute (FSI), examines the straightforward “same activity, same regulation” principle alongside so-called entity-based regulation. The latter comes into play “when entities perform a combination of regulated activities and that combination is considered to generate risks for the achievement of primary policy objectives.”

To arrive at the right formula for Big Tech, Restoy writes that “contrary to what industry and other observers often claim, there seems to be a strong case for relying more, and not less, on entity-based rules. The current framework could be complemented with specific requirements for Big Techs that would address risks stemming from the different activities they perform.”

Hints of Harmonization

The FSI and U.S. House documents, the European Union DMA and DSA, and internet competition guidelines put forward by China's State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) and prioritized by President Xi Jinping have entity-based elements. Therein lies potential for harmonization, which can be elusive on a truly global scale and can discourage loophole-seeking or regulatory arbitrage.

“These specific rules for Big Techs could include obligations for interoperability, limits on the bundling of services, prohibition of admission criteria leading to unfair discrimination against interested vendors, and constraints (or even bans) on the sale of their own products on the platforms they own,” says the Restoy paper. “Yet the most important - and most complex - issues are those related to the use of data obtained by Big Techs in their various activities. This comprehensive data availability constitutes a source of competitive advantage over other players (such as banks) in the market for specific financial services.”

Short of draconian restrictions that might cause market inefficiencies and consumer harm, Restoy says, data-driven dominance can be addressed with portability requirements like those in open banking regulations, and with enforceable rights as in Europe's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

But data regulation and control is just one piece of a policy puzzle so complicated and politicized that the Big Techs will remain, for a while longer, in a relatively regulation-free zone. Much of the current policy dialogue centers on antitrust law, and as Restoy states, “Antitrust enforcement actions are typically slow, and the standard of proof requested is very stringent. This may leave disruptive anti-competitive practices unsanctioned either indefinitely or until it is too late to reverse their adverse effects on competitors.

“There thus seems to be a case for considering the establishment of specific entity-based regulations for Big Tech platforms that would complement general competition law by restricting ex ante certain practices that could be considered anti-competitive.”

Official and Public Pressure

Legal and legislative wheels can turn slowly. Even two years ago, Facebook founder and chief executive Mark Zuckerberg knew they were bearing down, telling a congressional hearing: “The internet is growing in importance around the world in people's lives; I think it's inevitable that there will be some regulation.”

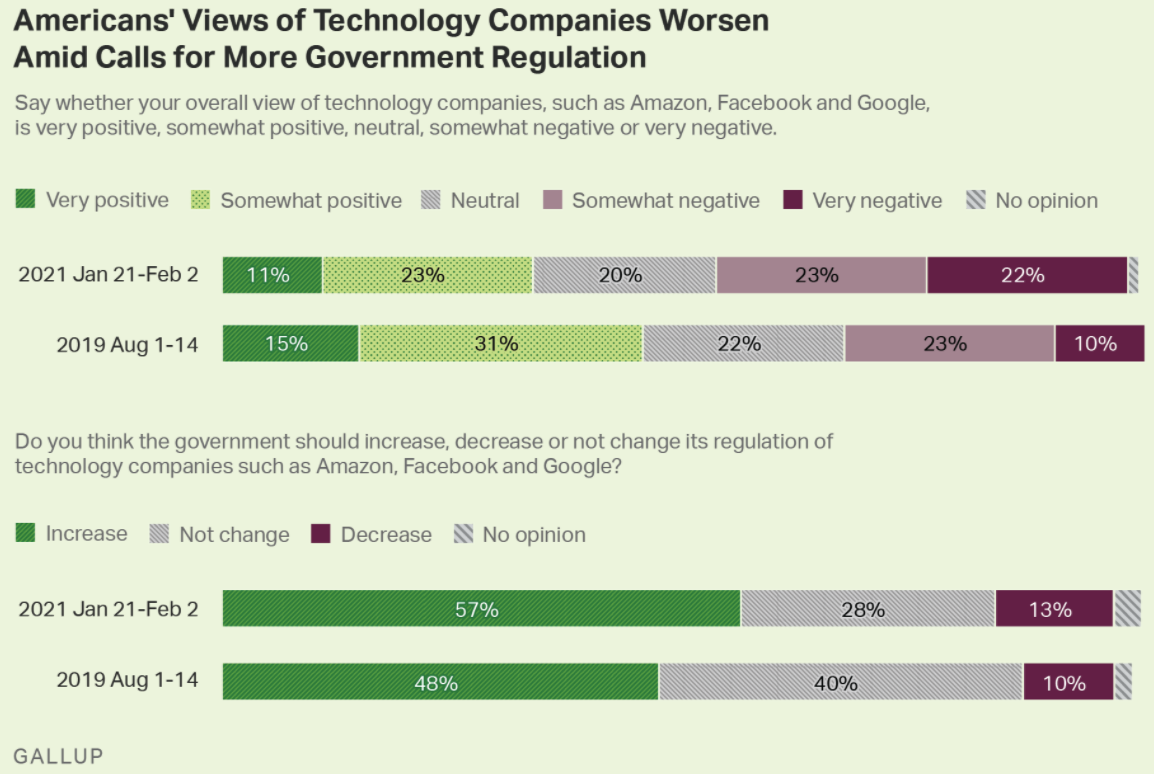

At that time, some members of Congress were more eager than others to push a formal regulatory agenda, but in the interim, and in the wake of misinformation and “de-platforming” controversies, Facebook and other Big Techs have been increasingly challenged by legislative initiatives, lawsuits and public opinion. According to a Gallup survey completed this February, 57% of U.S. adults favored an increase in regulation of these companies, up from 48% in August 2019. The proportion harboring very or somewhat negative views of the Big Techs jumped to 45% from 33%, while those with positive leanings declined to 34% from 46%.

Senator Amy Klobuchar, Democrat of Minnesota and chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee's Antitrust Subcommittee, has vowed to revitalize antitrust enforcement and resist further concentrations of power with the Competition and Antitrust Law Enforcement Reform Act. The former presidential hopeful has Big Tech in her sights, with indications of bipartisan support.

Representative David Cicilline, Democrat of Rhode Island and chair of the House Antitrust Subcommittee, presided at a March 12 hearing on the technology platforms' effects on a “free and diverse press,” and another March 18 with witnesses including Attorney General Phillip Weiser of Colorado, which has joined with most other states in antitrust litigation against Facebook. (Ten states also sued Google, alleging an advertising technology monopoly, with Facebook named in the complaint as a co-conspirator. On another front, Apple is battling French probes into data collection and advertising practices.)

A leading banking trade group, the Bank Policy Institute, sees a danger in alternative or special-purpose charters from the U.S. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and some states which are receptive to fintechs. These vehicles can “avoid the vast majority of (or all of) the prudential regulatory framework established by Congress and federal regulators,” while skirting the local commitments required by the Community Reinvestment Act and blurring the statutory boundary between banking and commerce, says BPI's keepbankingsafe.com website.

“Where fintech is leading,” it adds, “Big Tech is sure to follow.”

Beyond issues of competitive balance and fairness, International Monetary Fund managing director Kristalina Georgieva is concerned about “rising market power” - with larger firms growing and merging, resulting in less dynamism and R&D investing - as a threat to economic recovery.

“We see growing signs in many industries that market power is becoming entrenched amid an absence of strong competitors for dominant firms,” Georgieva and three co-authors say in a March 15 IMF Blog. Big Techs are a case in point: “The market disruptors that displaced incumbents two decades ago have become increasingly dominant players that do not face the same competitive pressures from today's would-be disruptors. Here the pandemic-related effects are adding to powerful underlying forces such as network effects and economies of scale and scope.”

Break Them Up?

As if to encourage the inquiries and actions underway in the U.S. and EU capitals, the IMF article recommends priorities for competition authorities including more vigilance in controlling mergers, investigative efforts to prevent market abuses, and “empower[ment] to keep pace with the digital economy, where the rise of big data and artificial intelligence is multiplying incumbent firms' advantage. Facilitating data portability and interoperability of systems can make it easier for new firms to compete with established players.”

In a Brookings Institution analysis following last fall's House Antitrust Subcommittee report, nonresident senior fellow Mark MacCarthy, a former House Energy and Commerce Committee staffer, described two routes to reining in Big Tech:

“Progressive reformers seem torn between breaking up today's tech titans or regulating their anti-competitive conduct. Many, including Senator Elizabeth Warren, Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes, and antitrust scholars Tim Wu and Lina Khan [both tapped as Biden administration appointees], seem to prefer a breakup. Others, including former chair of the Council of Economic Advisers Jason Furman . . . and former chair of the Federal Communications Commission [FCC] Tom Wheeler, call for a specialist agency to regulate the tech giants.”

Wheeler, now a Brookings visiting fellow, has written, “The market realities of the 21st century require a new regulatory structure of nimble oversight tools unpossessed by the agencies of today. That shortcoming can be resolved with the creation of a purpose-built federal digital oversight agency.”

“The EU seems to be moving quickly toward the regulatory approach,” MacCarthy continued, while “the House report asks, in effect, 'Why not do both?' It recommends separation of digital platforms from commerce and discouraging mergers resulting in 30% or more market share to prevent dominant company acquisitions and maintaining unconcentrated markets. The report also discourages acquisitions by dominant companies of direct competitor startups or startups operating in adjacent markets.”

Monopolies or Utilities?

MacCarthy pointed to two “separation” precedents: the 1984 split of AT&T into one long-distance and seven regional phone companies, which “worked only to a limited extent because the FCC imposed access requirements and other pro-competitive measures to enforce the pro-competitive thrust of the breakup”; and the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933's separation of commerce and banking. The latter “worked for generations only because it was vigorously enforced by the supervising banking regulators.

“Without ongoing supervision,” MacCarthy asserted, “the report's pro-competition measures will not be effective. A specialist regulator can do this and integrate other policy issues such as protection of privacy and the preservation of free speech into a unified policy approach.”

A more conservative voice, American Enterprise Institute visiting scholar Mark Jamison, expresses concern that the EU's DMA and DSA will treat Facebook, Google and others as electricity-like public utilities “with all of the typical utility obligations and constraints but none of the rights.” They would also lack the protections from competition that are part of the conventional utility bargain, “so look for Big Tech companies to begin losing out to rivals under these rules.”

Jamison, who served on former President Donald Trump's FCC transition team and is director and Gunter Professor of the Public Utility Research Center at the University of Florida's Warrington College of Business, sees another possibly slippery slope in regulating social media platforms as telephone-company-like common carriers. That “would either damage social media companies' businesses or incorporate protections from competition,” repeating past patterns in railroads, airlines, trucking and telecommunications, according to Jamison.

“Look for the Biden administration to embrace government involvement in content moderation,” Jamison wrote in January. “As this evolves, Big Tech regulation will become a multilateral issue, with officials from multiple countries playing leading roles and pursuing their individual interests. Customers will diminish in importance because governments will largely determine winners and losers.”

International Coordination

Those approaching Big Tech regulation from the banking perspective underscore its multilateral dimension.

The advent of Big Tech and fintech calls for “a more holistic blending of financial regulation, antitrust policy, and data privacy regulation,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland president and CEO Loretta Mester said in a November 2020 speech. “There will need to be cooperation across these types of regulators within each country, and this may entail creating structures that allow for more formal or systematic coordination across different types of regulators. The growth of digitalization also calls for a modernization of the antitrust laws and policy, which is occurring in several countries.

“The global nature of the Big Tech firms entering financial services means that effective international coordination among regulators and supervisors through the Financial Stability Board and other international entities will be critical to ensuring that the benefits can be captured and the risks managed.”

Carstens at the Basel, Switzerland-based BIS, and Restoy in his Financial Stability Institute paper, are taking the activity- and entity-based conversation to a global level.

“In some policy domains,” Restoy says, “such as consumer protection or AML/CFT, an activity-based approach may well be adequate enough to achieve primary objectives. Yet in others, such as financial stability, an entity-based approach is indispensable. In a third group of policies, such as those on operational resilience and competition, regulations require a combination of activity- and entity-based rules, addressing the specific risks that different types of players can generate to meet those policy objectives.”

When it comes to operational resilience, where stringent rules apply to banks and insurance companies: “As things move forward, and some Big Techs continue to increase their presence in the financial services market, their operations may acquire systemic importance. This should be acknowledged by the regulatory framework. A complication is that they operate across a range of financial and non-financial business lines, thus requiring cooperation across different authorities.”

“Finally,” Restoy adds, “with regard to competition, the potential of Big Techs to achieve a dominant position and to use that position to adopt anti-competitive practices may deserve specific action. An entity-based regulation targeting those risks, including rules that facilitate comprehensive and efficient data-sharing, seems a promising strategy.”

Restoy's “level playing field” paper was the subject of a Peterson Institute for International Economics virtual event on March 11. PIIE nonresident senior fellow and Georgetown University Law Center professor Anna Gelpern suggested “unpacking” such basic questions as who is regulated, by whom, and how. She cautioned against fragmentation, where one agency might regulate competition, another financial activity, which the “pace of change” renders too risky.

“Systemic Relevance”

Seeing the entity-based approach “gaining ground in major jurisdictions,” Carstens said that “specific provisions that aim at preventing data misuse and anti-competitive practices by Big Techs” represent a departure from competition policy that does not typically rely on specific rules being satisfied ex ante. “It rather builds on the ex post monitoring of the application of general principles and the development of case law.

“The European Commission's initiatives also include provisions for risk management procedures, transparency, auditing exercises and the supervision of Big Techs,” Carstens said. “A natural follow-up of those initiatives is to further study possible measures that address the potential systemic relevance of Big Techs and the need to introduce specific safeguards to guarantee sufficient operational resilience. That may be especially relevant for Big Techs offering key services (such as cloud computing) to financial institutions worldwide.”

That might raise the possibility of “systemic importance” designations, as with banks and financial market utilities, though “the current framework falls short of allowing for the recognition of the potential (possibly global) systemic impact of incidents in Big Tech operations and of possible spillover effects to the financial sector and across all the activities Big Techs perform,” Carstens said. “For this and other reasons, regulatory actions in this area would benefit from close coordination among different financial and non-financial regulators, at both the national and global level.”

“From a broader point of view,” the BIS chief concluded, “the rise of Big Tech has underscored how rapidly digital innovation can disrupt markets, even leading to new concerns around systemic importance. Authorities cannot be caught asleep at the wheel. We must invest in monitoring and understanding these developments, so as to be prepared to act quickly when needed.”

An FSI Brief posted March 16 by institute deputy chair Juan Carlos Crisanto and two co-authors elaborates on the challenge of “understand[ing] and keep[ing] abreast of Big Techs' continuously evolving business models.” Regulators need a clear picture of services being provided locally and across borders, “the modalities under which they are offered (e.g. through partnership with other financial institutions or own-licensed entities, or as 'matchmakers'), and how Big Techs monetize data. Clarity on these features is critical to identify where the ultimate risk of their activities resides.

“What regulators are increasingly appreciating is that, while Big Techs share a number of key characteristics, no two are alike. Thus, the risks they generate might differ depending on their core business line, which may have implications for the 'right' approach to be taken by an authority.”