The crisis of 2008 sensitized the financial industry and its regulators to threats to economic and systemic stability. Policy reforms, designed to prevent worst-case recurrences, were accompanied by financial stability assessments, now adding up to reams of annual commentary and statistical analysis, from central banks, the International Monetary Fund, other official bodies and academic observers.

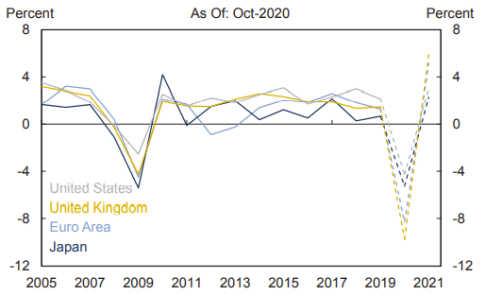

Suddenly, in 2020, the stability evaluations took on new urgency as the coronavirus pandemic set off a worldwide economic decline that made a Great Depression scenario more plausible than a mere replay of 2008. After years of tracking the longest recovery on record, systemic risk assessments in the latter months and weeks of 2020 gained added significance as report cards on the condition of the financial sector and where it may be headed in 2021 and beyond.

There is general agreement that banks withstood the pandemic shock because of the stronger liquidity and capital positions that ensued from the 2008 crisis - one that was rooted in the industry's credit excesses, in contrast to the exogenous virus outbreak. Financial institutions are regarded as part of the solution, rather than a cause.

Some relief, even self-congratulation, shows through. The annual report of the U.S. Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), released on December 3, cited various Federal Reserve credit facilities, regulatory relief measures, loan forbearance, and the $2.6 trillion CARES Act stimulus as factors in propping up the economy and investor sentiment.

Heath Tarbert, chairman of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, an FSOC member and one of the report's signatories, said that while “the COVID-19 outbreak was an extraordinary shock to the global financial system and led to substantial financial stress . . . it did not lead to a financial crisis. During this real-world, real-time test of the resilience of our markets, of our market participants, and of our agencies, all three have performed exceptionally well.”

No Victory Lap

But economists remain concerned about clouds on the horizon, ranging from the effects of further waves of the disease and related lockdowns, to total global debt that S&P Global estimates will reach $200 trillion, or 265% of GDP, by year-end.

“Of course, we cannot take a victory lap,” CFTC's Tarbert said. “Risks to U.S. financial stability remain, and the magnitude of those risks is tied at least in part to the severity and duration of the ongoing pandemic.”

In the IMF's October Global Financial Stability Report: Bridge to Recovery, financial counsellor Tobias Adrian wrote that a total of $7.5 trillion in G-10 central banks' balance sheet expansion and $12 trillion in global fiscal expenditures helped to contain “the adverse macro-financial feedback loops that were so prevalent and pernicious in the 2008 crisis.” Countries' and firms' access to capital market and bank funding was preserved, and liquidity pressures did not lead to “broad-based insolvencies.”

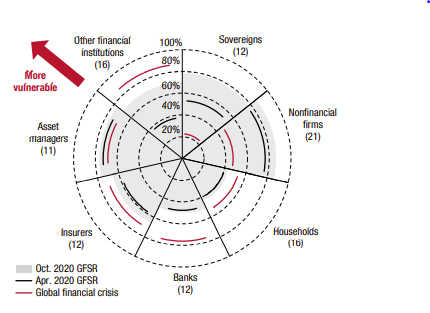

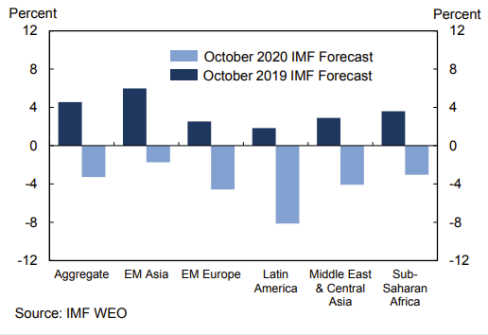

At the same time, “financial vulnerabilities are rising, putting medium-term macro-financial stability and growth at risk.” Adrian pointed to “stressed valuations in risk asset markets,” growing corporate debt, fragilities in the nonbank financial sector and “a weak tail of fragile banks in some countries . . . Furthermore, sovereign debt is at historically high levels. This is a critical issue for many low-income countries and some emerging market economies, where a debt crisis might be inevitable without prompt and decisive policy action.”

As of the Bank of England's financial stability report in August, the financial system was effectively supporting U.K. households and businesses, buoyed by “the resilience that has been built up since the global financial crisis” and extraordinary government and central bank policy responses.

BOE's Financial Policy Committee deemed banks to be “resilient to a very wide range of possible outcomes. It would therefore be costly for them and for the wider economy to take defensive actions [such as cutting lending]. It remains the FPC's judgment that banks have the capacity, and it is in the collective interest of the banking system, to continue to support businesses and households through this period.”

In the BOE December stability report, released on the 11th, the FPC was reassuring on several counts: The U.K. "banking system remains resilient to a wide range of possible economic outcomes," despite headwinds including high unemployment and uncertainties related to the Brexit transition; "can absorb credit losses in the order of £200 billion," 10 times 2020's bank loss provisions and "much more than would be implied if the economy followed a path consistent with the [Monetary Policy Committee's] central forecast"; and can expect the countercyclical capital buffer to remain at 0% - below the standard 2% - at least until 2021's fourth quarter (in effect, a year later because of the buffer's implementation lag).

Elevated Risks and Contagion

“Though policy actions to minimize the effects of the pandemic have been effective at improving market conditions, risks to U.S. financial stability remain elevated compared to last year,” concluded the FSOC, a panel created by the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, consisting of the chiefs of federal supervisory agencies and chaired by the secretary of the Treasury. “In addition, the global outlook for economic recovery is uncertain, depending on the severity and the duration of the ongoing pandemic.”

The Office of Financial Research (OFR), in its 177-page annual report on November 18 - its first “written in the wake of a material and unexpected threat to financial stability,” in the words of director Dino Falaschetti - similarly judged financial stability risks to be elevated across macroeconomic, market, credit, liquidity and other categories.

As part of its Bank Systemic Risk Monitor, the OFR, which principally supports the FSOC, maintains a Contagion Index - a gauge of banks' interconnectedness and spillover effects in the event of default. Failure of one of the eight U.S. global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) “could pose a threat to the international financial system,” the office says, and “foreign G-SIBs are a potential source of contagion for U.S. banks with cross-border claims on these institutions.”

An analysis of international banking claims in the Bank for International Settlements' December Quarterly Review found them to be “strikingly resilient” in comparison to 2008. While global output year-on-year fell 9.1% through the first half of 2020, global cross-border claims were up 4.8%, “one of the highest yearly growth rates” since the last crisis.

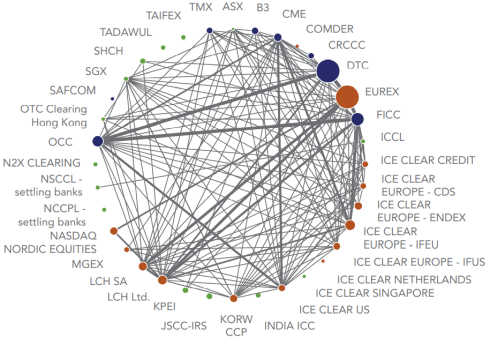

The OFR has also mapped interconnections among central counterparty (CCP) clearing entities for contagion risks, saying, “Even though CCPs have several layers of protection against potential default by one or more members, risks remain . . . If a CCP were to default, or the member had defaulted at several CCPs, there could be substantial contagion effects due to interlocking memberships and loss spillovers on members' balance sheets.”

One of the systemically important CCP utilities, Depository Trust & Clearing Corp., released its annual Systemic Risk Barometer survey on December 2. Out of 220 respondents identifying their top five “risks to the global economy,” 67% mentioned infectious disease/pandemics - 31% ranking it No. 1 - after it did not come up at all a year earlier. Cyber risk, the next-most-frequent among top-5 answers, fell to 54% from 63%. That was followed by the U.S. presidential election outcome (50%), geopolitical risks and trade tensions (45%) and excessive global debt (33%).

Well down the ranking was “CCPs as single point of concentration,” dropping to 5% from 10%.

Research “Blind Spots”

Another of the OFR's bullet points pertains to the state and adequacy of the data required to monitor financial stability and improve the ability to forecast.

Stability reports “may have potential to become more valuable still by complementing information produced by conventional monitoring of vulnerabilities (which tends to rely on a naturally limited handful of research and data insights) with insights from people who are most knowledgeable about where and when those vulnerabilities might reveal themselves,” OFR said. “A mechanism for doing so might lie with better developed 'prediction' or 'information' markets, where people who have superior information about answering consequential questions can have relatively strong incentives to share their insights more freely.”

In a November 20 speech to a conference sponsored by the OFR and Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, OFR director Falaschetti said that the pandemic experience has revealed “limits to how researchers typically evaluate threats to financial stability,” and how “conventional monitoring tools can be prone to material blind spots.” He noted that “in 2019, about 30 central banks, multilateral organizations, and government agencies around the world issued official financial stability reports, including the OFR. Yet, not one discussed the potential for a pandemic to threaten financial stability.”

The FSOC underscored the importance of data sharing among regulatory agencies, asserting that “gaps and legacy processes” inhibit such communication. Although “important steps have been taken, including developing and implementing new identifiers for financial data,” since 2008, “significant gaps remain,” the council said. It called for more work by regulators and market participants on “coverage, quality, and accessibility of financial data,” and on data standards and harmonization in the mortgages and derivatives areas.

View from the ECB

During the November 23 Financial Regulatory Outlook Conference, organized by consulting firm Oliver Wyman and the Centre for International Governance Innovation, European Central Bank supervisory board member Elizabeth McCaul likened the onset of the current crisis to an “intense storm.” The ECB sprang into action with the objective of “keeping banks lending to sustain a recovery,” even as a severe vulnerability scenario indicated that nonperforming loans could reach €1.4 trillion.

“Some of the uncertainty is dissipating,” McCaul said. “Now we know much more, even though the cloud cover is remaining very thick.”

Another conference panelist, SociÉtÉ GÉnÉrale chairman Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, said that what is lacking now is regulatory certainty and consistency to stimulate lending by a banking sector that is constrained by high capital buffers, and to encourage private capital flows for asset securitizations and potential cross-border banking consolidations.

The ECB's Financial Stability Review in November acknowledged euro area banks' resilience and capital levels, warned that “weak profitability prospects continue to weigh on bank valuations,” and said “downside risks to bank profitability arise from a weaker outlook for lending volumes and signs of optimistic provisioning.”

A special feature in the review explored the ramifications of a “low-for-longer interest rate environment,” suggesting that “the longer interest rates remain low, and in the absence of a rebound in inflation expectations, the more of a drag on euro area bank net interest margins they can become . . .While low rates should help keep the cost of risk lower than otherwise, an increasing drag from squeezed margins is, other things being equal, a significant challenge to bank profitability.”

FSOC Alerts

“Vulnerabilities include structural weaknesses in the financial system and its regulatory framework,” said the FSOC. “Vulnerabilities in the financial system can amplify the impact of an initial shock, potentially leading to substantial disruptions in the provision of financial services, such as the clearing of payments, the provision of liquidity, and the availability of credit.”

The FSOC devoted a 21-page chapter of its 200-plus page report, which is a third longer than the prior year's, to “potential emerging threats” in financial markets, such as wholesale funding, money market funds and repo. Among others requiring vigilance: commercial and residential real estate, nonbank mortgage origination and servicing, central counterparties, the transition from the Libor benchmark to alternative risk-free rates, the advent of digital assets and stablecoins, and cybersecurity threats stemming from “greater reliance on technology, particularly across a broader array of interconnected platforms,” as well as remote-working arrangements.

One of the FSOC's mandates is to identify financial stability risks that could arise from the activities, distress or failure of large, interconnected bank holding companies (BHCs). Severe and prolonged economic deterioration “can affect the resilience of the banking system,” the council stated. “Financial distress at a large, complex, interconnected BHC has the potential to affect global financial markets and amplify the negative impact on economic growth by further tightening credit conditions.”

“Large and complex U.S. financial institutions were more resilient prior to the pandemic than they were prior to the 2008 financial crisis,” FSOC found. “This resilience has been achieved, in part, by raising more capital; holding higher levels of liquid assets to meet peak demands for funding withdrawals; improving loan portfolio quality for residential real estate; implementing better risk management practices; and developing plans for recovery and orderly resolution.

“The council recommends that financial regulators ensure that the largest financial institutions maintain sufficient capital and liquidity to ensure their resiliency against economic and financial shocks,” said the report, adding that regulators should “continue to monitor the capital adequacy for these banks and, when appropriate, phase out the temporary capital relief currently provided.”

Outside Advice

The OFR noted in its report that “crystal ball forecasts of systemic vulnerabilities or crises have proven infeasible,” and director Falaschetti pointed out that “COVID-19 disruptions were worse than the most severe stress tests projected.” In raising the possibility of implementing some form of prediction market, the FSOC-linked agency is signaling a desire for and openness to new sources of insight.

Prediction or information markets are said to tap the “wisdom of crowds” - provided that those investing, or placing wagers, in these information exchanges possess at least some relevant expertise. At best they could “help reveal costly or otherwise hidden information that can play a fundamental role in creating systemic risks,” OFR explained.

“Markets such as these can be efficient, and frequently outperform competing mechanisms such as polls for aggregating otherwise dispersed information,” said the report. Falaschetti, a former House Financial Services Committee chief economist who has held several university faculty positions in law and economics, co-authored a 2010 University of Pennsylvania Journal of Business Law article, An Information Market Proposal for Regulating Systemic Risk.

Meanwhile, financial policy experts, advisers and academics are continually probing and proposing ways to enhance and refine systemic-risk and stress-testing analytics. A few examples:

- In a June article, Steering Banks Through the Crisis, Oliver Wyman said that many planning scenarios are “too simplistic,” and “financial institutions need new critical inputs from outside the sector, especially from the world of healthcare,” to manage through the pandemic and understand the implications of lockdowns and behavioral changes in their markets. “Banks need to identify a set of scenarios for the evolution of the pandemic based on epidemiological data and the likely containment strategies,” Oliver Wyman said. “These scenarios will provide a common foundation for a range of use cases, from operational planning of when and how to return to work, to understanding the impact on customers and their financial services needs and risks. In addition to establishing these core scenarios, it is important for banks to reverse stress test, understand which scenarios would truly make them change course, and know what the signals are for those.”

- In a Brookings Institution report, Fixing Financial Data to Assess Systemic Risk, Yale School of Management research scholar Greg Feldberg says that the OFR's effectiveness could be improved by removing “roadblocks,” such as how it “sits organizationally” within the Treasury Department, and providing more funding than it had during the Trump administration. “Legacy data-collection technologies, old-school thinking and bureaucratic turf fights continue to hinder the authorities' ability to monitor systemic risks,” says a summary of the December 2 report. “Moreover, U.S. regulators have fallen behind the private sector and many of their peers overseas in the adoption of technologies that could revolutionize the collection, management, sharing and dissemination of financial data.”

Feldberg recommends that the incoming Biden administration “empower the OFR to do its job and coordinate a systemwide financial data strategy, working with FSOC. That strategy should include near-term targets for finally addressing data gaps in repos, securities lending and derivatives; accelerating the use of the LEI [Legal Entity Identifier] by the private sector; and launching a long-term initiative to modernize data collection, management and sharing in the regulatory community.”

- Whereas most financial stability research centers on exogenous shocks to the system, a paper presented to the OFR-Cleveland Fed conference by USC Marshall School of Business PhD candidate Chong Shu examines risk exposures that banks choose - those arising in connected networks of banks. The study “reverses the previous intuition about the stabilizing effect of a highly connected financial system,” adding observations on how “connected banks tend to make similar bets, especially in the 2008 global financial crisis.” The correlated risk exposure aggravates systemic fragility. According to the model, a central counterparty, “although providing co-insurance to its member banks, can create moral hazard and systemic instability. The model also suggests that capital regulation should consider banks' systemic footprint.”

Another OFR-Cleveland Fed conference speaker was Joshua Epstein, a New York University professor of epidemiology and a contributor of scientific expertise to discussions of financial system vulnerabilities, panics and contagions - a subject explored by, among others, MIT Sloan School of Management finance professor Andrew Lo and Princeton University ecology and evolutionary biology professor Simon Levin (see A New Approach to Financial Regulation). Epstein is a pioneer in agent-based modeling and author of Agent_Zero: Toward Neurocognitive Foundations for Generative Social Science.

- A September article in the Marsh & McLennan BRINK series, Does the World Need Its Own Risk Management System?, quoted David Wood, chair of London Futurists: “We need global leaders and budget holders to wake up to the responsibility that there are greater numbers of large risks out there than ever before. Large risks are changing from matters of occasional concern to matters of constant concern.”

Wood, also principal of the firm Delta Wisdom, went on: “We need to be immersed in discussions of credible scenarios for what might and might not happen, rather than just Hollywood films. We need to become much more literate at understanding the risks of outbreaks of infectious diseases, as well as the other risks of contagion, whether it's financial contagion, or malware contagion, or fake news contagion and so on. And we need to understand things more probabilistically. Probability is a difficult concept, but we need to help people understand it, so when things like bird flu or SARS or MERS happen, the public appreciates that things could well have turned out very differently.”