June 25 was a busy day for the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Its open meeting resulted in approvals of two final rules, withdrawal of a previously proposed rule and supplemental proposal, and the advancing of two additional proposed rules. Just the day before, in step with other federal financial regulators, CFTC backed removal of Volcker Rule prohibitions on banks investing in so-called covered funds.

That modification alone does not fix what CFTC chairman Heath Tarbert views as fundamental flaws in the overly broad Volcker Rule implementation, but it corrects what “Congress never intended to be included in the first place,” investments in the likes of credit funds, venture capital funds, customer facilitation vehicles, and family wealth management vehicles. There were also some easings with respect to private equity and hedge funds.

On those points, Tarbert and the commission - albeit by a 3-2 vote - fall in line with the current administration's consensus on rolling back some provisions in the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act, a bias perhaps reinforced by the strains of current, pandemic-related economic conditions. In one of its June 25 actions, the CFTC cited COVID-19 as it pushed back a deadline for smaller firms to comply with initial margin requirements on uncleared swaps.

But on another matter, Tarbert's assertions set himself apart from many of his peers. With increasing regularity since taking office in July 2019, the CFTC chief has been advocating principles-based regulation, which would represent a turn away from the rules-based specificity that is the modern norm.

The concept, which has been debated but never fully embraced in regulatory and policy circles, “reflects a transition away from detailed, prescriptive rules toward high-level, broadly-stated principles that create standards by which regulated firms must operate,” Tarbert explains in a recent Harvard Business Law Review article. “Under this approach, firms are responsible for finding the most efficient way of achieving regulatory objectives.”

Historical Practice

The CFTC, established in 1974, has a principles-based tradition, “solidified,” Tarbert says, by the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000. Electronic Trading Risk Principles, approved by a 4-1 commission vote on June 25, gave the chairman a chance to show how it can work.

Under the proposal, which was opened for a 60-day public comment period, exchanges are required “to take steps to prevent, detect, and mitigate market disruptions and system anomalies associated with electronic trading,” Tarbert said.

Going beyond existing rules centering on price swings and volatility, “the proposed risk principles would expand the term 'market disruptions' to cover instances where market participants' ability to access the market or manage their risks is negatively impacted by something other than price swings,” Tarbert added. “This could include slowdowns or closures of gateways into the exchange's matching engine caused by excessive messages submitted by a market participant. It could also include instances when a market maker's systems shut down and the market maker stops offering quotes.”

Who Knows Better?

An applicable tenet of principles-based regulation is to acknowledge that “regulated entities have greater understanding than the regulator about the risks they face and greater knowledge about how to address those risks.”

For “an area where exchanges are likely to possess the best understanding of the risks presented and have control over how their own systems operate,” Tarbert said, the commission laid out principles “subject to a reasonableness standard” for compliance.

“Through thoughtful analysis of the regulatory objective we aim to achieve, the nature of the market and technology we are addressing, the sophistication of the parties involved, and the nature of the CFTC's relationship with the entity being regulated, we can identify what areas are best for a prescriptive regulation or a principles-based regulation,” the chairman continued. “In the present context, a principles-based approach - setting forth concrete objectives while affording reasonable discretion to the exchanges - provides flexibility as electronic trading practices evolve, while maintaining sound regulation.”

Tarbert expressed hope that Electronic Trading Risk Principles “will serve as a framework for future CFTC regulations. Electronic trading presents a prime example of where principles-based regulation - as opposed to prescriptive rule sets - is more likely to result in sound regulation over time.”

A Role for Rules

Tarbert does not say that rules-based regulation has no place. “What I am going to try to articulate is when it makes sense and when principles makes sense,” he said in October 2019 in the annual Robert Glauber Lecture at Harvard University's Institute of Politics.

Rules can be advantageous, for example, in providing a clearer standard of behavior for regulated entities, or a safe harbor from private litigation.

Tarbert includes among the beneficial qualities of principles-based regulation simplicity, flexibility, promotion of innovation, discouragement of “loophole behavior,” and facilitation of international cooperation. In addition to automated trading, he has mentioned position limits, cross-border regulation, and digital assets as appropriate for a principles-based approach.

“While the [digital assets] market develops further,” says Tarbert's journal article, “CFTC staff is considering how the core principles applicable to derivatives exchanges and clearing organizations can be augmented given the rapid developments in the fintech space.

“This may result in the CFTC adding core principles for derivatives exchanges and clearing organizations, or it may necessitate the CFTC providing high-level guidance regarding the application of existing rules and regulations to cutting-edge developments.”

Not Light-Touch

A University of Pennsylvania Law graduate, former head of Allen & Overy's bank regulatory practice, and a Treasury assistant secretary and acting under secretary before joining the CFTC, Tarbert insists that principles-based is neither light-touch regulation nor a euphemism for deregulation, as has been asserted in opposing arguments.

Justifiably or not, light-touch policies in the U.K. have been blamed for exacerbating effects of the 2008-'09 crisis and making it harder for principles-based proponents to make their case. Tarbert has pointed to a 2011 Guardian article quoting then U.S. Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner: “The United Kingdom's experiment in a strategy of 'light-touch' regulation to attract business to London from New York and Frankfurt ended tragically.”

Tarbert's rejoinder in the Harvard Business Law Review: “No principle, however noble, can be effective if it is ultimately left toothless.”

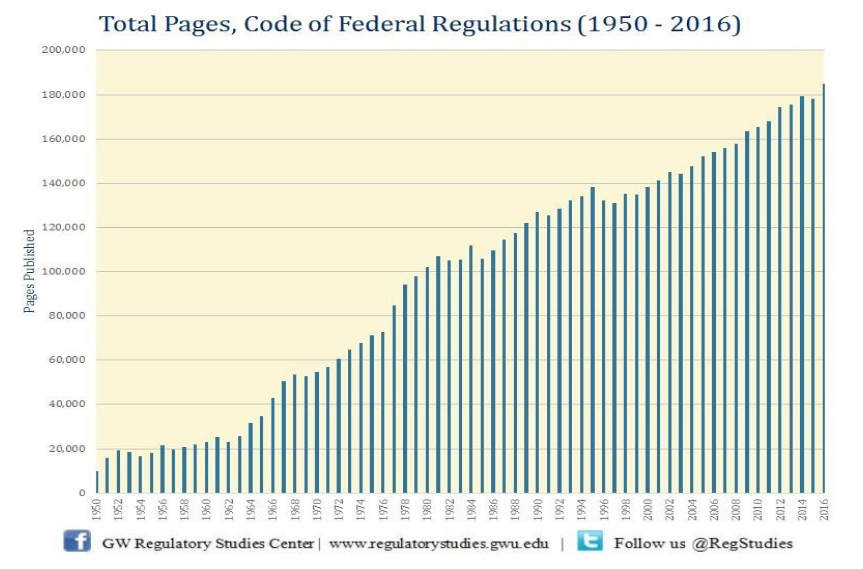

Principles-based holds appeal, in part, because of the “general consensus that we've had a little bit of an information overload in terms of rules,” Tarbert said in the Glauber lecture. “I think there's also a consensus among everyone that for risk and other types of features involving our financial system, we shouldn't treat Main Street institutions the same way we treat Wall Street institutions. So things have gotten a little bit out of hand. Regulation has grown quite enormous-- a 10-fold increase since 1950.”

Andrew Bailey, then chief executive of the U.K. Financial Conduct Authority, now governor of the Bank of England, said in an April 2019 speech, “Left to our own devices, I think the U.K. regulatory system would evolve somewhat differently. It would I think take on board practical experience more rapidly, and it would be based more on principles that emerge from experience in public policy and somewhat less on detailed rules that can tend to become overly set in stone.”

Federal Reserve Board vice chair for supervision Randal Quarles discussed principles of a different sort - those that supervisory agencies should abide by - in a February 2020 speech on transparency, accountability and fairness in bank supervision. Multilateral bodies also propound principles that filter down to individual jurisdictions, such as with the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision's on risk data aggregation.

Dissent Within

Even the commission with a principles-based tradition isn't completely unanimous.

Concurring with the principles-based electronic trading proposal, CFTC's Brian Quintenz, who is sponsor of the commission's Technology Advisory Committee, said, “DCM [designated contract market] trading and risk management controls continue to evolve with the trading technology itself. As we have witnessed over the past decade, risk controls are constantly being updated and improved to respond to market developments. It is my view that these continuous enhancements are made possible because exchanges and firms have the flexibility and incentives to evolve and hold themselves to an ever-higher set of standards, rather than being held to a set of prescriptive regulatory requirements which can quickly become obsolete.”

However, Commissioner Rostin Behnam cast the dissenting vote on Electronic Trading Risk Principles, as well as opposing the concurrent withdrawal of Regulation AT (Automated Trading), which included controversial risk control requirements and potential access by the regulator to firms' proprietary source code.

Behnam said in his statement that “as I considered this proposal, I found myself questioning what the proposed risk principles do differently than the status quo. The preamble seems to go to great lengths to make it clear that the commission is not asking DCMs to do anything.”

“It is worth noting that the commission described the unanimously approved Reg AT proposal as principles-based,” Behnam said. “Multiple commenters to that proposal noted that it was too principles-based. I suspect that each of us on the commission believes that the CFTC has a tradition of principles-based regulation, and that that tradition should continue. However, I think there is disagreement as to precisely what that means.”

Behnam referred in a footnote to remarks he made in 2018: “The best principles-based rules in the world will not succeed absent: (1) clear guidance from regulators; (2) adequate means to measure and ensure compliance; and (3) willingness to enforce compliance and punish those who fail to ensure compliance with the rules.”

Commissioner Dan Berkovitz, while defending the withdrawn Reg AT, said of the trading risk principles that his support for a final rule will be “conditioned upon a thorough articulation of the technology-driven risks present in today's markets, and a concomitant regulatory response that will meaningfully address such risks. In a market environment where the vast majority of trading is now electronic and automated, inaction is a luxury that we can ill-afford.”