-1.jpeg)

Banks ramped up loan-loss reserves at the onset of the pandemic because of the current expected credit losses (CECL) accounting standard that went into effect at the start of 2020. Although losses have been low so far, and the economy is improving as vaccinations accelerate, institutions remain cautious about releasing those reserves. Losses are still considered likely, and concerns about CECL's methodology persist.

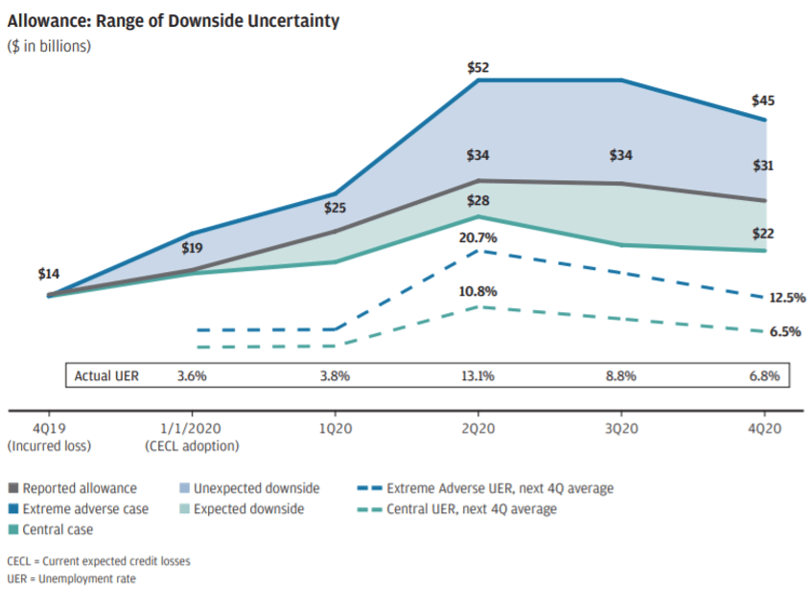

JPMorgan Chase & Co., for example, released $1.9 billion in reserves in the 2020 fourth quarter but still maintained more than $30 billion, even after posting earnings that well exceeded analysts' expectations. Chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon, in a statement reported by CNBC, said the reserve level reflected “significant near-term economic uncertainty and will allow us to withstand an economic environment far worse than the current base forecasts by most economists.”

In his more recent letter to shareholders, Dimon said, “After probability weighting multiple scenarios, we ended the year with $31 billion in reserves.” He said the bank is capable of handling large increases in reserves and stressed that “CECL does not change risk management or the way we run the company. We have been lending, and will continue to lend, to our clients and customers throughout the pandemic with prudent risk management.

“Our credit risk decisions and broader risk appetite are mostly driven by our clients' needs and market conditions rather than solely by reserve methodology,” Dimon continued. “While reserve levels are an estimate reflecting management's expectations of credit losses at the balance sheet date, they may not reflect the amount of losses ultimately realized.”

JPMorgan released a heftier $5.2 billion in the first quarter, still maintaining $26 billion in reserves.

Reasons for Caution

The reserve reversals among the big banks that did occur stemmed in part from improving economic factors, but more from shrinking loan growth, according to Michael Gullette, senior vice president, tax and accounting at the American Bankers Association. He noted that some banks detailed their provisions for loan growth or deterioration, and he anticipates more such analyses.

In Wells Fargo & Co.'s fourth quarter earnings call, president and CEO Charles Scharf couched an “extremely positive” outlook with the need “to be prudent.” He noted that “the only meaningful reserves” the bank reversed resulted from a student loan sale, “which we had to do,” and retaining the reserves maintained balance-sheet strength going into 2021.

Hesitancy to decrease allowances relates to perceived likelihood of losses, at least in certain sectors. In addition, while the CECL-mandated forward look gives banks desirable flexibility to adjust reserves, their forecasts need to be quantifiably justified to satisfy auditors. And worries persist that CECL presents pro-cyclical risk, pushing banks to increase capital reserves when economic conditions make it most problematic.

The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and its constituents wrestled with the pro-cyclicality issue in the years when CECL was being developed. For example, should signs of significant losses emerge later this year just as another financial crisis arises - perhaps interest rates skyrocket because global investors shed Treasury bond holdings - banks under CECL would have to rapidly build capital positions just as their earnings are shrinking and losses peak.

What Could Have Been

Having to raise capital levels when profits are down is “the doomsday scenario,” said Laurent Birade, senior director, risk and accounting solutions, Moody's Investors Service.

Such a scenario could have happened last year, if banks following CECL rules had ramped up loan-loss reserves in the second and third quarters - which they actually did - while pandemic-related shutdowns led to widespread defaults. Government stimulus along with loan modifications and forbearance gave businesses a lifeline, but at least in hard-hit sectors such as retail, hospitality and commercial real estate (CRE), a reckoning may still come.

“The long-term impacts remain unclear - and there's the risk they're potentially being masked by those [government] programs,” said Murilo Brizzotti, principal industry consultant at SAS. “The impacts are likely to surface more prominently as such incentives begin to expire.”

Birade said that during the 2008 financial crisis it took eight quarters on average for losses to peak, although federal aid came much later after the crisis began. This time around, because the government acted so quickly, the peak will likely be lower and with some delay.

“The general sense is that it will depend on the bank's portfolio,” Birade said.

Commercial Real Estate

In CRE, Gullette said, collateral prices have dipped in pockets but appear to have remained relatively strong, yet that strength may be illusory due to the forbearance and deferment programs and a dearth of transactions over the last year.

He added that in 2010, CRE collateral prices fell faster and further than market participants expected. If that happens this time, it could create major challenges, especially for smaller regional and community banks whose portfolios tend to hold greater CRE exposure.

“You could have stress in many banks if collateral values start going down,” Gullette said, “If they do, people will ask, 'Why didn't CECL forecast this?'”

“Right Direction”

Brizzotti described CECL as a “very important step in the right direction” compared to the backward-looking incurred loss method previously used, since it allows institutions to consider macro-economic scenarios and potential future outcomes and to adjust reserve allowances accordingly. However, the SAS consultant added, CECL models were not prepared for the extreme swings in unemployment and the financial impact of forbearance.

“On top of that, mortgage forbearance was extended until June 2021,” he said. “Coupled with a recent drop in the unemployment rate, lenders may be facing a situation in which models may now be underestimating the loss potential,

“Banks must continue to closely monitor how delinquency levels and usage of forbearance programs are evolving.”

Key Data Points

Birade of Moody's noted three factors drive changes to banks' CECL calculations: economic-forecast data, including unemployment, the home price index, commercial property index and likely future prepayments; loan portfolio characteristics, including lien positions, seasonal activity and a portfolio's average loan age; and credit quality, measured by such data as delinquency trends, credit bureau scores and net charge-offs.

The economic forecast is likely to have the greatest impact on reserve allowances, and through the pandemic it has also been one of the most volatile and difficult to support quantitatively.

“What we've seen from last December through March is that some economic indicators were thought to be able to rebound much faster, but in Q1 we're realizing that maybe it won't be as fast as we thought, and this may have a counter-intuitive impact on certain portfolios like CRE,” Birade said before the quarter ended. He added that first-quarter reserve releases were unlikely to exceed 10% or 15%, although that is more than twice December's increase.

That estimate was largely borne out in early April earnings reports. JPMorgan, Bank of America and Wells Fargo released 20%, 15% and less than 10% of reserves, respectively.

Gullette said CECL has brought to the forefront the need to focus on the economic forecast. While it enables banks to zero in on their portfolios' different loan types - consumer vs. commercial, commercial and industrial vs. office, etc. -it has also revealed the need for much more granular analysis.

He added that granularity was a common concern in recent ABA roundtables with both large and smaller banks, especially given the uncertainty government intervention introduced to factors such as unemployment and commercial borrowers' ongoing viability.

Part of the underlying concern, Gullette said, is new auditing requirements developed around the same time as CECL that require quantitative support to minimize “management bias,” as loan-loss reserves can be based on many qualitative judgments. CECL gives banks the flexibility to make qualitative adjustments, but according to Public Company Accounting Oversight Board and American Institute of CPAs guidance, auditors will want to see as much quantitative backing as possible.

“The big banks had a grip on that,” Gullette said. “They've understood progressively over the last few years that that is where we're headed, but the smaller banks [under $30 billion in assets] not so much. They're saying, 'How do we support these adjustments?'”