Adoption of the Current Expected Credit Loss (CECL) standard couldn't have come at a worse time. Earlier this year, companies and investors were just getting used to the idea of embedding forward-looking estimates into financial reporting when the most severe economic shock since the Great Depression hit.

Given the enormous market volatility and the difficulty of forecasting in a time of extreme uncertainty, some are now questioning whether we should cancel the whole CECL experiment. However, doing so would be costly and counterproductive.

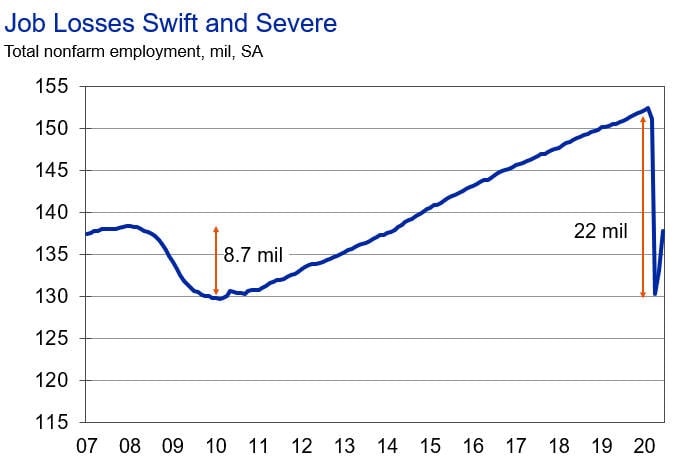

The recession of 2020 will go down in history for its extraordinary breadth and depth. US GDP declined by over 33% on an annualized basis in the second quarter. Officially, over 22 million workers lost their jobs within a matter of weeks, with millions more likely under-reported.

Figure 1: Unemployment Skyrockets

Based on Moody's Analytics data, no country escaped a contraction - a development without precedent in modern economic history, as some part of the world has always remained stable or expanded when other countries slipped into recession.

Loan Loss Reserves: Uncertainty Adds to Complexity

In this extreme environment, accountants and risk managers were challenged to implement a complex new accounting rule. Economic forecasts evolved rapidly throughout March, as new information about the spread of the coronavirus and government and business responses to it were released daily. Loss projections for existing loan portfolios fluctuated greatly as a result, further complicating the analysis.

Ultimately, CECL filers had to impose some judgment - not only on the performance of the economy going forward but on the response of borrowers under conditions never previously observed.

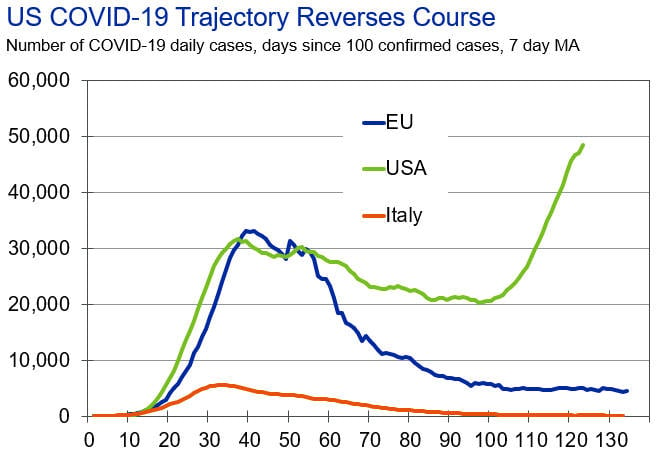

Following March's volatility, the hope was that mandatory lock down measures and voluntary social distancing would lead to a sharp decline in the number of daily coronavirus infections in the United States, just as in many Asian and European countries. But things certainly haven't gone as planned.

In late May, US state and local governments began loosening restrictions before case counts had fallen to sufficiently low levels. While re-openings did enable millions of people to go back to work, infections accelerated throughout June, threatening another wave of social distancing and business closures.

As a result, CECL filers are once again challenged to estimate future lifetime losses in an unstable environment.

Figure 2: COVID-19 Cases

Adding to the confusion, the short-term credit losses that had been anticipated for the second quarter, in an environment of double-digit unemployment, failed to materialize. In fact, delinquency rates on some portfolios (such as student loans and mortgages) declined, as unemployment insurance payments and generous forbearance programs offered a temporary lifeline to distressed borrowers.

But how many of these defaults have just been delayed versus avoided? This is the million- or billion-dollar question for many risk managers today. The answer can mean the difference between reserving too much or too little.

CECL vs. the Incurred-Loss Model

Given uncertainty on top of uncertainty, would we be better off under the old incurred-loss model? By waiting until borrowers breach a threshold of probable loss before booking a loss allowance, we avoid all of this ambiguity about if and when a borrower is going to default.

Without a doubt, the incurred-loss model is easier to implement than CECL. But it's also extremely misleading and tantamount to sticking our heads in the sand in the face of what is likely to be the biggest economic shock in our lifetime.

At best, the incurred-loss framework failed to provide investors with any information they didn't already know during the last recession. At worst, it led some banks to wait too long to add to their loss reserves and hastened their own demise.

Investors and bank analysts are smart people. They understand that forecasts are subject to change, along with earnings. Given the right information, they can adjust, question and evaluate risks. But data and disclosures are critical to this process.

For all its flaws, CECL provides much more information about a bank's risk profile than the incurred-loss model ever did. That alone is one reason to keep it.

Another key consideration is that CECL's sole focus is financial reporting, not capital adequacy. Capital calculations and regulations are outside the purview of the accounting standard-setters.

The Federal Reserve took an important step at the end of March, when it gave filers more time to recognize CECL's impact on capital calculations. By doing so, the Fed clarified its position that capital rules should act in a countercyclical fashion to lean against, rather than exacerbate, the business cycle.

This rule change sharply reduced the risk that CECL adopters would have inadequate capital during this uncertain time. It put bank managers' minds at ease, and is the reason why criticism of the CECL rule has all but disappeared. Once the spotlight was placed on the true source of concern - capital adequacy - objections to CECL's unintended consequences subsided.

Remaining Obstacles, and Potential Solutions

While the CECL procyclicality debate is put on hold by the COVID-19 crisis, it does not minimize the very real challenges CECL filers continue to face under extraordinary conditions.

Many credit loss models built on historical data are struggling to produce reasonable estimates in an environment characterized by double-digit unemployment and massive GDP declines. The prospect of negative interest rates would also wreak havoc on mathematical models expecting strictly positive values.

In the short term, modeling options include adjusting inputs or qualitatively adjusting forecasted loss estimates. Each approach has both advantages and disadvantages. CECL's flexible “reasonable and supportable” language allows each institution to adopt the best approach, given their own unique circumstances.

Longer term, credit loss models may need to consider missing variables such as borrower income and assets. Credit scores, for instance, may need to be adjusted for the economic cycle, and we may want to reconsider whether unemployment rate is the best predictor of default risk.

While modeling issues will continue to be researched and contested, one debate the coronavirus has definitively put to bed is the use of forward-looking scenarios for loss forecasting.

Given the possibility of forecast uncertainty, we need to regularly consider multiple scenarios in our projections and planning. We must also build systems that are flexible and fast enough to respond to shifting conditions. Resiliency and adaptability are far more important than the false precision of a complex statistical analysis of history.

Parting Thoughts

COVID-19 hasn't killed CECL, but the standard needs to be adapted to consider a broader range of risks and to provide investors with the information necessary to make informed judgments. The coronavirus crisis has highlighted the need for even more timely data and disclosures.

CECL isn't perfect, but it's an important step in the right direction.

Cristian deRitis is the Deputy Chief Economist at Moody's Analytics. As the head of model research and development, Cris specializes in the analysis of current and future economic conditions, consumer credit markets and housing. Before joining Moody's Analytics, he worked for Fannie Mae. In addition to his published research, Cris is named on two U.S. patents for credit modeling techniques. He can be reached at cristian.deritis@moodys.com.