Banks typically benefit from rising interest rates as spreads widen between assets and liabilities, yielding better profit margins. But the current cycle, defined by a series of increases that followed an extended period of near-zero rates, left banks with significant mortgage-backed securities (MBS) holdings facing deteriorating profits, or as was the case with Silicon Valley Bank’s mismatched long-term assets, potentially existential crises.

The failed SVB had $210 billion in assets. Of those, $87 billion were agency MBS, collateralized mortgage obligations and commercial MBS, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. said when it tapped BlackRock to sell those securities as well as $27 billion from Signature Bank, which also entered receivership in March. Agency MBS in April “recovered slightly from a poor prior month,” and “sales from bank seizures have been taken in stride,” according to a Refinitiv analysis.

The aggregate asset-liability equation changed dramatically over the last year. At the start of 2023, some online banks and thrifts were paying around 4.5% on five-year certificates of deposit and other incremental funding sources, and more than 5% in April, while sizable swaths of asset portfolios were in the 3% range.

“The earnings impact could be fairly immediate, with net interest income likely having peaked for several banks, but the magnitude of earnings declines may take some time to play out, depending on the duration of the bank’s assets and the stickiness of their liabilities,” said Nick Caes, credit analyst at Janus Henderson Investors.

The Tide Can Rise

Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council data, Bloomberg reported at the end of March, indicated that at year-end 2022, banks with at least $25 billion in assets had a total of $620 billion in unrealized losses. Those with sizable unrealized losses relative to tangible equity included Bank of America, U.S. Bank, Truist Bank and Charles Schwab Bank.

FDIC Chairman Martin Gruenberg

FDIC Chairman Martin Gruenberg quoted the same unrealized-loss figure in March 28 Senate Banking Committee testimony, warning that “additional short-term interest rate increases, combined with longer asset maturities, may continue to increase unrealized losses on securities and affect bank balance sheets in coming quarters.”

A draft paper posted in March by New York University’s Stern School of Business, adding in loan data, said the unrealized losses on bank credit could have been as high as $1.7 trillion – approaching total bank equity capital of $2.1 trillion.

The authors noted that “the proximate reason” for regulators’ intervention with SVB was that it “suffered a bank run after announcing a large loss on selling some of its mortgage-backed securities. The loss on MBS was caused by an increase in interest rates due to the Federal Reserve’s monetary tightening. As of writing, there are increasing concerns about similar problems at other banks.”

Said Gruenberg: “It is important that we, as regulators, message to our supervised institutions that [facilities such as the Federal Reserve discount window and Bank Term Funding Program] can and should be used to support liquidity needs. Sales of investment securities have been a less common source of liquidity as the level of unrealized loss across both available-for-sale and held-to-maturity portfolio remains elevated.”

Banks Are Biggest Holders

Although mortgage rates have fallen, from 7% in early March, they remained significantly higher than the coupons on banks’ existing MBS holdings, which have dropped in value as investors eye MBS with higher returns. Unrealized losses would become actual losses if institutions had to sell those assets to increase liquidity.

In House Financial Services Committee testimony on May 16, Federal Reserve Vice Chair for Supervision Michael Barr raised the possibility of reconsidering capital requirements based on a bank’s size and risk: “Had SVB been required to reflect declines in the face value of available-for-sale securities in its capital, it may have held more capital to cover these losses.”

Barr added that such a change would take several years to be phased in following “the standard notice and comment rulemaking process.”

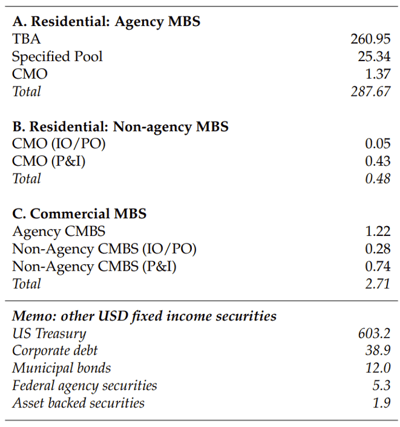

Depository institutions are the largest class of investors in MBS, as of mid-2021 holding 32% of outstanding MBS, followed by the Federal Reserve at 23% and international investors at 11%, according to a February 2022 Federal Reserve Bank of New York staff report.

Average daily trading volumes in 2021, in billions of dollars, as shown in Mortgage-Backed Securities, Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Mark Slattery, head of asset-liability management (ALM) and integrated balance sheet management solutions at SAS, said those percentages likely remain about the same. Per the New York Fed report, 80% of outstanding agency MBS carries a coupon of 4% or lower.

He added that about 80% of MBS had been originated over the five years prior to March 2021, and 42% in the year before that date. Furthermore, mortgages continued to be originated at low rates until the Fed began its tightening in March 2022. That suggests banks have significant low-coupon MBS on their books.

Meager Refinancings

Banks’ outflows of low-cost deposits were accompanied by liabilities costing more than the returns on MBS assets, with little prospect of borrowers refinancing into loans that provide banks with higher returns and improve their asset-liability spread.

“Unless you have a serious life event that drives you out of that home, you’re probably not going to look to increase your cost of funds by a factor of two,” Slattery said.

The Bloomberg US MBS Index, reflecting agency MBS prices, was trading around 90 in mid-April. “That’s telling us that prepayment incentive is so far out of the money that literally 1% of borrowers have economic incentive to refinance,” said John Kerschner, head of U.S. securitized products at Janus Henderson. “Even if mortgage rates rally by 200 basis points, only 10% of borrowers out there would have an economic incentive to refinance.”

In mid-April, he noted, mortgage prepays were 5% or less, according to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac data, when it’s typically closer to 20%.

Locational Differences

Although many banks have at least partially hedged the impact of rising rates on their balance sheets those actions do little to hedge what Slattery referred to as extension risk, when rates rise and MBS duration increases. The longer banks have to hold on to existing MBS and whole mortgages – some priced below 3% amid record-low rates at the start of 2021 – the more they could eat into earnings.

Kerschner said that ongoing asset-liability management challenges will likely result in more banks failing, as nearly 500 did in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis, between 2008 and 2012. About 75 failed since then.

Slattery said banks holding on to significant volumes of whole mortgages or MBS with coupons of 3.3% or lower are particularly at risk if interest rates remain high. He added that another gauge of mortgage portfolio risk will be loan-level analysis and taking into consideration factors such as location, loan-to-value ratios and borrower FICO scores. States with more vibrant economies and mortgage markets should adjust more quickly to the rate environment, and thus less extension risk.

“If you do a deep dive into an MBS and find a concentration of mortgages in slow-growth areas of California or Illinois, there will likely be some issues there,” Slattery said. “Location has always been an important consideration, but it might be even more critical at this point.”

Topics: Default