Amid a generally healthy run of economic indicators, the conversation at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C. was strikingly alarmist. The panelists at a February 12 discussion on global financial market risks - including AEI resident fellow Desmond Lachman and Harvard Kennedy School professor Carmen Reinhart - raised warning flags about debt levels and leveraged lending.

Lachman described corporate debt as “off the charts,” abetted by mispricing of credit risks and further compounded by a lack of flexibility among policymakers, should their intervention become necessary.

Reinhart, co-author with Kenneth Rogoff of the post-financial-crisis history “This Time Is Different,” agreed with most economists that a U.S. recession is not imminent. In a National Association for Business Economics survey of 281 members between January 30 and February 8, 10% expected a recession in 2019, 42% in 2020, and 25% in 2021.

Reinhart said residual effects from the last recession are still playing out globally. “Prospects of a sustained slowdown are real and already under way,” she said, pointing her finger at corporate debt as a point of vulnerability.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.'s Quarterly Banking Profile on February 21 was a typical reflection of market-condition contrast. U.S. insured institutions posted a near-record $59.1 billion in aggregate net income in 2018's fourth quarter. Yet, FDIC chairman Jelena McWilliams pointed out, “Low interest rates and an increasingly competitive lending environment have led some institutions to reach for yield, and the recent flattening of the yield curve may present new challenges in lending and funding. Therefore, banks must maintain prudent management of these risks in order to support lending through this economic cycle.”

Stability Implications

Such signals are not the first of their kind. Regulators and central bankers have been increasingly insistent in recent months in calling attention to higher-yielding, often below-investment-grade leveraged lending.

Total outstanding leveraged loans and high-yield bonds in Europe and the U.S. have doubled, to about $2.65 trillion, since the financial crisis, according to the Bank for International Settlements.

As noted in a Bloomberg report, at the U.S. Federal Open Market Committee's September meeting, “some officials said the growth of leveraged loans and looser standards present 'possible risks to financial stability.'”

Then-U.S. Treasury Department chief risk officer and Office of Financial Research acting director Ken Phelan wrote in his letter accompanying the OFR's annual report last November that overall credit risk, on balance, was moderate, “with risk rising from leveraged lending, tempered somewhat by risks from consumer credit.”

Signs of Deterioration

The body of the OFR annual report went into more detail:

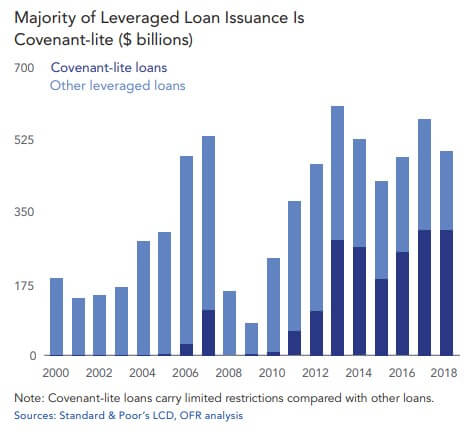

“Rapid growth in leveraged lending is a concern . . . With the growth in leveraged lending has come a deterioration in the credit quality of newly issued loans. One sign of this decline is the high share of covenant-lite loans [see graph]. Covenants are restrictions placed on debt-issuing firms meant to increase the likelihood of payment. Another sign of deterioration in underwriting quality is that more than half of all leveraged loans issued are rated B+ or lower (that is, highly speculative).”

A participant in the February 12 AEI panel discussion, just after departing the Treasury, Phelan noted that leveraged corporate debt has nearly doubled in a little more than a decade, to $1.5 trillion, and the number of corporations with leveraged debt has risen to 1,500, from 800 in 2012.

Government borrowing did not escape Phelan's critique: “We don't have a sustainable way to finance our debt.”

Monetary Factor

In a wide-ranging global outlook speech at a February Financial Times event, Bank of England governor and former Financial Stability Board chairman Mark Carney noted that with the reversal in monetary-policy accommodation, “after five years in which there was no new net issuance of G7 government debt, new government borrowing outweighed central bank purchases by more than $1 trillion for the first time since 2012.”

“Potentially more seriously,” Carney went on, “the slowing in global momentum may also be the product of rising trade tensions and growing policy uncertainty . . . If all measures contemplated are implemented, average U.S. tariffs will reach rates not seen in half a century.”

The central banker acknowledged that “some are beginning to wonder whether the global expansion, begun in 2010, could be starting to end,” and then dug into the topic of corporate debt: “more of a concern, particularly in the U.S.” He noted that “relative to earnings, aggregate corporate debt in the U.S. and U.K. is nearing pre-crisis peaks, and the share of highly levered companies in the U.K. is above pre-crisis levels “despite the very modest growth in investment.

“Globally, the average quality of corporate borrowers has deteriorated materially,” Carney said. “The share of lower-rated debt in global corporate bond markets has increased significantly over the last 10 years, with BBB-rated bonds now about half of the market, compared to just a quarter in 2007.”

Comparison to Subprime

Carney said that the global leveraged lending market's 21% growth in 2018 was faster than that of U.S. subprime mortgages in the run-up to the global financial crisis. “At $2.3 trillion,” he said, “the stock of outstanding leveraged loans is double that of subprime in 2007 . . . 60% of leveraged loans are now covenant-light, and most deals have substantial 'add backs' of EBITDA. These are developments analogous to the 'No Doc / No Income' heyday of U.S. subprime.”

One additional parallel: “growth in leveraged loans has been increasingly driven by securitization.” But, Carney concluded, “the main holders of leveraged loans can generally bear the risks,” and the core of the financial sector is more resilient: “Banks in most regions are now more likely to be stabilizers rather than amplifiers of shocks. Regulation has made banks less complex and more focused. They lend more to the real economy and less to each other. Trading assets have been cut in half, and interbank lending is down by one-third.”

He described it as “a judgment, not a guarantee” that “global growth is more likely than not to stabilize eventually around its new, modest trend . . . The world is in a delicate equilibrium. Productivity is weak everywhere. The sustainability of debt burdens depends on interest rates remaining low and global trade remaining open. And business and consumer confidence are being buffeted by extreme policy uncertainty.”

He came back to subprime mortgages and how “they eventually grew unchecked” until those written in 2006 and 2007 “were twice as likely to default as those originated just a few years earlier. It is just such a descent from responsible to reckless underwriting that we must avoid today.”

Two AEI panelists were openly skeptical of crisis response and management by a more unilateral U.S. Desmond Lachman said that the Trump administration “has gone out of its way to burn the bridges with the countries we need to deal with. Speed is of the essence.”

William White, past chair of the Economic and Development Review Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, said, “We haven't succeeded in crisis prevention. We need crisis management more than ever.”